Winston Churchill, with a Little Bit of Luck

The First Post In a New Series Exploring Historical Nonfiction Books

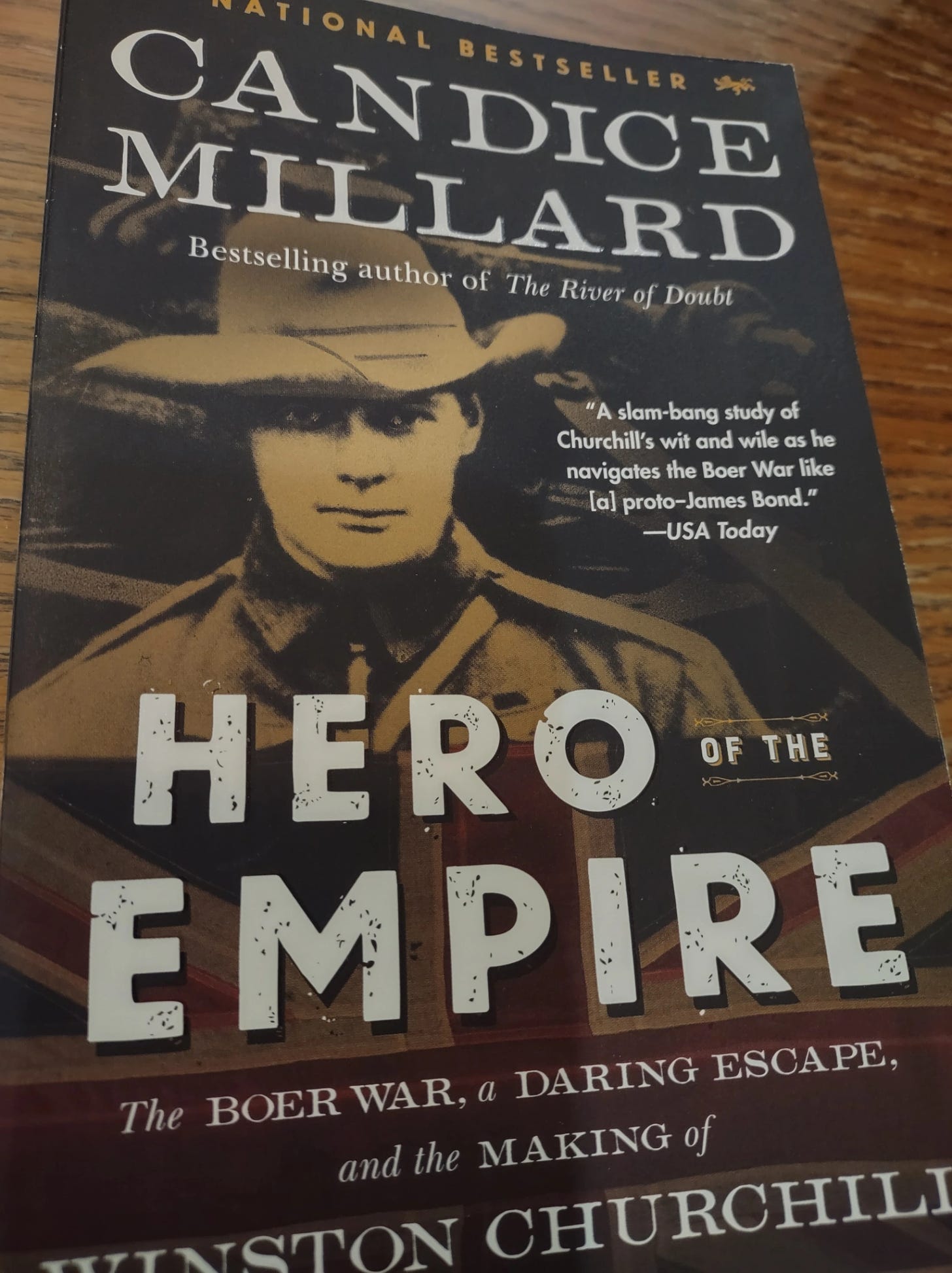

Hero of the Empire, by Candice Millard, zeroes in on a low point in Winston Churchill’s life—when he was taken prisoner during the Second Boer War in 1899.

Captivity was antithetical to Churchill’s whole nature. Granted, it’s antithetical to most people’s nature, but Churchill was especially poor at enduring such a state. As Millard explains, while other prisoners kept in shape, Churchill neglected to exercise and, uncharacteristically, struggled to maintain his concentration while reading.

Escaping, however, gave him the sort of struggle he needed, and the danger seemed to rejuvenate him.

I highly recommend Hero of the Empire: The Boer War, a Daring Escape, and the Making of Winston Churchill for the full details. Millard provides great insight into the character of young Churchill (only in his twenties at the time), as well as a general introduction to the history of South Africa at the dawn of the twentieth century.

But as this book focuses on one small part of Churchill’s long life, I just want to focus on one small part of that small part.

Churchill’s escape, though originally devised by a couple of other prisoners whom he had to leave behind, would never have happened without his own courage, initiative, and resourcefulness. The ultimate success, however, also depended on a little bit of luck.

Bad luck, inevitably, also played a role. Churchill’s plan to board a passing train at night fell through because, as a wartime measure, all trains were forbidden to run after 7 p.m. He considered asking native Africans for help, since they hated the British slightly less than they hated the Boers. He started to approach what he thought was a group of natives but couldn’t bring himself to follow through.

“Churchill continued walking for about a mile in the direction of the fires, struggling with his fears and doubts, and then he stopped, overwhelmed by a sense of the ‘weakness and imprudence’ of his plan,” Millard writes.

Churchill would later write that he was “completely baffled, destitute of any idea what to do or where to turn.”

“This time, for perhaps the first time in his life, he was paralyzed with indecision,” Millard writes.

Somehow, the clouds of doubt lifted—“by no process of logic,” Churchill later said—and he continued on toward the fires, his sense of purpose renewed. But as he neared, he realized he wasn’t approaching a camp of native Africans. He was approaching a coal mine.

This, too, carried risks, perhaps even greater risks, but Churchill was simply too exhausted to withdraw and resume wandering. He had the sense that doing so wouldn’t end well for him.

So he approached the nearest house and knocked on the door.

A man answered, and Churchill improvised a lie about having had an accident. The man wasn’t buying it, though, and Churchill soon saw no other option but to take his chances and tell the truth.

Millard quotes the man as saying, after Churchill revealed his identity, “Thank God you have come here! … It is the only house for twenty miles where you would not have been handed over. But we are all British here, and we will see you through.”

The man’s name was John Howard. He was hired to run the coal mine and had been living in the Transvaal for years, eventually becoming a naturalized citizen. His British origins had excused him from fighting in the war, and his current standing had allowed him to remain in the area.

Howard, at great personal risk, organized the ultimately successful efforts to smuggle Churchill to safety. Had Churchill knocked on any other door that evening, his fate—and possibly the later history of World War II—might have turned out very differently.

“By an incredible stroke of luck, Churchill had stumbled upon one of the few places in the 110,000 square miles of the Transvaal where it was still possible to find an Englishman,” Millard says.

This got me thinking about a key difference between nonfiction and fiction. One of Pixar’s rules of storytelling states, “Coincidences to get characters into trouble are great; coincidences to get them out of it are cheating.”

Absolutely true. Whenever a lucky break saves a character in any work of fiction, it just comes across as hollow and can lead to the story feeling pointless and unsatisfying. It might even break suspension of disbelief entirely.

But in nonfiction, when a real-life coincidence saves a real person in a real situation, it’s amazing. And it’s fascinating to consider how the arc of history hinges on some lucky breaks along the way. This is, of course, in addition to a whole lot else, but serendipity is part of the historical equation, too.

Churchill’s successful escape required his own initiative, the help of other capable people, and a pinch of that secret sauce, luck.

Daniel Sherrier is a writer living in central Virginia. A William & Mary graduate, he worked for community newspapers for nearly a decade as a reporter and then an editor. He is the author of the superhero novels The Flying Woman and The Silver Stranger, and he overthinks stories and writing on his own Substack. He is NOT a historian, but loves reading about history and sharing interesting books.