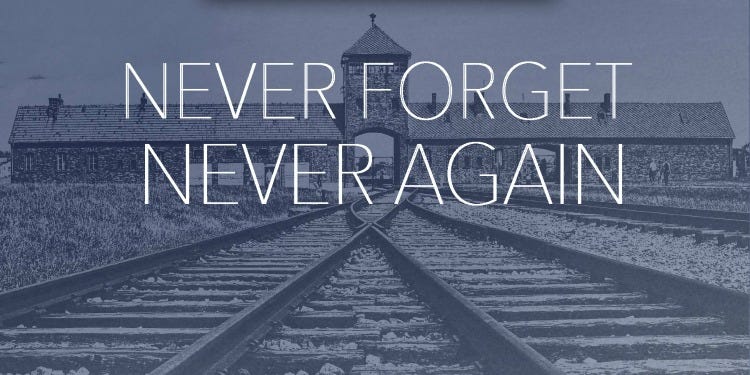

If you're even a casual reader of this publication, you'll have noticed that, while we feature short stories, movie reviews, podcasts, and humorous pieces, our greater mission is to publish and promote art and artists that oppose antisemitism.

David Swindle, my partner in publication and in life, has been a Zionist activist, using his writing talents to fight an ominous and growing strain of antisemitism, for many years now. He's passionate about defending the right of the Jewish people to exist in their home state of Israel, and he's determined to bring increasing awareness to the terrible fact that crimes based in Jew-hatred are not merely the stuff of history books, but are actually current news stories. He's so obsessively concerned with this issue, in fact, that the only unifying criterion for publication on this platform is a writer's sympathy with Israel and the Jewish people of the world.

He gets strident about it. He gets aggressive. He even gets profane.

And - surprise! I'm generally a pretty happy-go-lucky, gentle person, but I'm pretty much on board with this. Some of Dave's rhetorical tactics aren't my go-tos, but I'm entirely behind the cause.

During my time with Dave, people have found ever more creative and oblique ways to inquire of me what, exactly, his - what our - interest is in combating antisemitism. I know what they're asking: no, he is not Jewish - not by ethnicity and not by religion. I, too, am not Jewish, neither by ethnicity - that would be mostly Germanic, with one English-descended grandparent - nor by religion, either - that would be Quaker. (Well. Let's say Quaker-Spiritualist.) In fact, through my grandmother's English heritage, my family traces our Quaker heritage to the very first years of the movement.

So it isn't an explicitly personal interest - at least, not in the way we have come to expect. Perhaps we are so used to today's identity politics that it surprises us when people take up a cause that does not seem to be “their own.” Dave has shared with you at length the many rewarding Jewish influences he's had over his lifetime - surrogate grandparents, mentors, friends - who brought him to great sympathy for the Jewish people and religion. At the risk of playing armchair psychologist, I surmise, too, that as someone who has often felt like an outsider in life, there exists some natural solidarity, also.

But that's all well and good for him. Why, exactly, do I care? Well, perhaps paradoxically, I care because of my Germanness and my Quakerness. I'll address my Quaker inspirations in a second essay, but here, I'll discuss the ways in which my German experiences have informed my desire never to see antisemitism sanctioned again.

I am not in any kind of minority as an American with German heritage. It's pretty common. What's a little less typical is having a great-grandparent who emigrated from Germany in the 20th century - the biggest wave of German immigration to America was much earlier. Less common than that is taking it upon oneself as a German American to become fluent in that harsh, guttural old-country language, as I did. And you hear even less about German Americans who actually move to Germany, walking the same cobblestone streets and drinking the same beers as our ancestors. I did that, too.

I could write ten essays about all that I discovered there (spoiler: it was me! I discovered myself!). One area of basic knowledge that I delved much more deeply into, however, was that of World War II and the Holocaust.

I had some typical tourist experiences: in museums, I vomited at the displays of victims' personal effects that had miraculously stayed out of the officers' pockets and away from the ovens; I wept at photos, blown up life-sized, of terrified Jewish children and their anguished parents being herded onto cattle cars.

At Bavaria's Dachau, the very first concentration camp of the Nazi regime, I felt overwork, torture, and death hanging in the air around me like smog. The camp was originally conceived to sequester political enemies and conscript them into labor at an existing munitions factory, but, under the leadership of Heinrich Himmler, Dachau's function soon turned toward eliminating enemies of the “Aryan utopia.” Over 40,000 people died there during the twelve years that the camp was operational, from 1933-1945. The gas chambers at Dachau were never used, inexplicably, and the murders were, thus, less systematic and much more personal.

Upon approaching the compound, I promptly ruined the day by being so deeply distressed that I had to leave almost immediately. I didn't understand: for me, the victims, numb with horror, half dead, and dressed in those sickening blue and gray striped rags, were practically still there. Why were people laughing and posing for pictures? Others studied their maps as they moved from building to building, making notes and highlighting must-sees - I couldn't even walk in a straight line. I had hoped to bear witness to the crematoria, but I would've fainted. I'm embarrassed to say I turned right back around and left.

But the ghost of the Holocaust followed me in my daily life, too, not just at tourist sites. My first home in Germany was Passau, a beautiful and very old Bavarian city on the Danube that was remarkably unspoiled. I learned later that Passau had hosted three subcamps of the Mauthausen-Gusen complex, but no one was in a big hurry to point that out to me. Enchanted and oblivious, I passed my days in my very own fairytale: I went to school in a proper palace, with velvet tapestries on the walls and suits of armor displayed in corners. In my free time, I loved to explore its castles and museums; its convents and monasteries, all of which were reached via winding, narrow alleys. Despite how picturesque it all was, I still remember the jolt I felt looking on a map, seeing “Jewish quarter” - a medieval ghetto - marked as plain as day on a small peninsula, a strip of land nestled between the Danube and Ilz rivers. Of course, that Jewish population had long since been driven out, but those buildings, those tiny little apartments, were still there. As I wandered through the quarter, I couldn't help but wonder about the lives those people lived, so proscribed, shaped by the meagre mercy of others - or lack thereof. Who was living there now? Did they know? Did they care?

I left a part of my soul in Passau. I did it on purpose, so I'd have to come back and get it. Unfortunately, when I learned that this exquisite city of my dreams had once been home to Adolf Hitler himself, I wished I hadn't. Someone told me that the Austrian city of Linz, more readily recognized as Hitler's hometown, was visible down the Danube on a clear day. I was no expert at identifying Austrian towns from a distance, but I always felt like that evil man was somehow watching from over the Alpine foothills. Certainly his horrific campaign of hate loomed much further, even, than that.

But the nexus of my experience with Nazism in Germany came a few years later. Through an extraordinary feat of public record-tracing, a German friend helped me locate the granddaughter of my German great-grandfather’s brother. While he had come to America to work in a factory in Ft. Wayne, Indiana, he had left siblings behind. I was fascinated to meet with this relative, whom I'll call Elsa Hauptmann, for her privacy. Though it was sixteen years ago, I remember much of our conversation.

She was older than my parents, but very well put-together, I thought, as we met for a cup of coffee on the street of a gray Berlin café that could've been anywhere in the world. Elsa asked me how I liked Germany; I told her I loved it and was enjoying learning something about my own family history and culture.

She frowned and lit a Gauloises. I followed suit, not understanding.

“Your family history is in America,” she told me, with the naked German frankness that's so often misinterpreted as hostility. “It's not here.”

“But … I'm of German ancestry on both sides of my family. And … I really like it here. I feel like I'm learning about the way my ancestors lived.”

Elsa exhaled and sipped her cappuccino. “What are you learning?” she asked.

“Uhhh …” I blinked. “Well, I'm learning what it felt like to live in this place.”

She laughed, not unkindly. “'This place' was all different countries when your ancestors were here. Neighboring states now were enemy kingdoms. And at the time that your great-grandfather left, it was worst of all.”

This was what I wanted to know: what role the Hauptmanns who stayed behind had played in the lead-up to World War II. Speaking English, I'd have tried to couch such questions in softening verbiage, since it was a sensitive subject. But such linguistic gymnastics didn't translate, and anyway, it wasn't how Germans preferred to converse.

“What did they do during the war? Your grandfather? Your family?”

Lighting another Gauloises off the tip of the first, Elsa explained to me that they fought. That was just what you did. You fought to keep yourself safe and out of trouble. And very often, you “fought” without ever shooting a gun or physically harming people in any way. For every front-facing uniformed soldier, she said, there were dozens who wore suits to work in fairly ordinary office buildings, operating behind the scenes to power the great engine of the Reich.

I knew this. I know I did. But somehow, I needed to have it spoon-fed to me.

As Elsa stood up to go, she told me, “We were not there. We don't know what we would've done. It is not so easy to judge.”

I didn't think I had judged. In fact, I'd purposely kept my face impassive. And I agreed with her assessment entirely. Still, Elsa declined to take my email address. I never saw her again.

This is a complicated legacy for Germans to grapple with. Most Germans I know are disgusted at the reality of Hitler's rise to power and attempts to exterminate Europe's Jewish population - along with, of course, Slavs, Romani people, LGBTQ+ people, disabled people, Jehovah's Witnesses, and various other “undesirables.” It is a truly sickening reality, and one that Germany has worked hard to ensure is not repeated.

For better or for worse, my ancestors did leave Europe and come to America. My great-grandparents and grandparents and parents met and fell in love, and a bunch of other tiny factors fell perfectly in line, too, such that I exist and live a comfortable life with a man I admire and adore.

And we have a platform. It's true that I can't know how I'd have behaved if I'd been alive in Nazi Germany. But luckily, I can choose what I do with my life right now. Fighting antisemitism is important to my partner, and my experiences in Germany, before our journeys converged, made it important to me, too. So I am very happy - proud, even - to stand with David and say loudly that the sanctioned, systematic elimination of entire religions must never be allowed to happen again.

It's a slippery slope. And, folks, rocks are sliding.

A very interesting essay. You should read an article from the current Atlantic magazine that discussed how Germany and Germans are dealing with the legacy of WW2 and the Holocaust. If I can figure out how to access it online, I'll send it to you. Bonnie