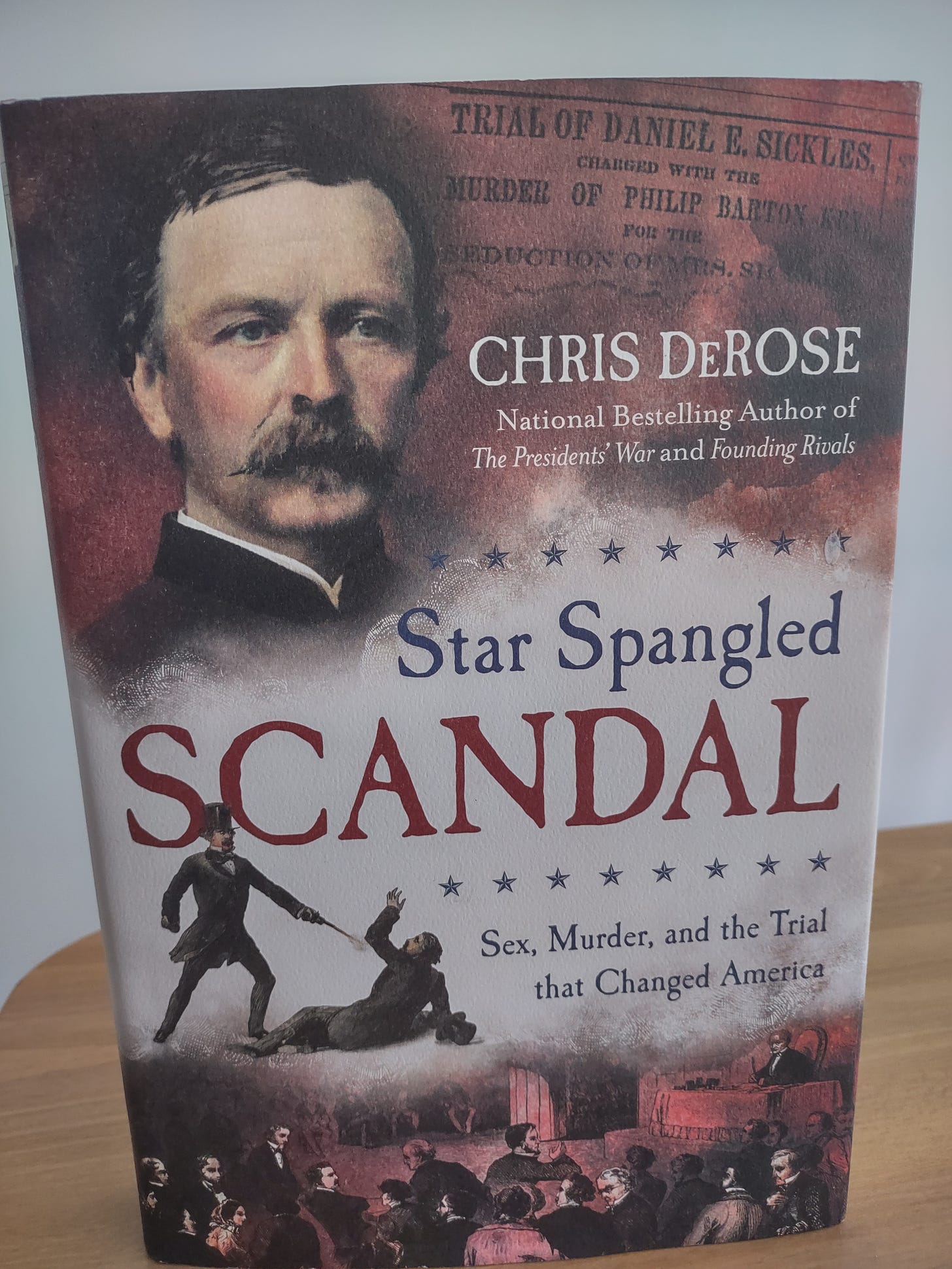

An unwritten law can be a dangerous thing, as shown in Star Spangled Scandal by Chris DeRose.

The book details an 1859 murder trial that was the first to whip up a media frenzy in the age of telegraphs. U.S. Congressman Daniel Sickles shot and killed U.S. Attorney Philip Barton Key—son of Francis Scott Key, it so happens—in the nation’s capital, under the clear light of day. Key and Sickles’s wife, Teresa, had been having an affair, so Sickles sought to avenge and restore his family’s honor. And he didn’t let the law get in his way.

Sickles had a team of skilled lawyers defending him in court, including future secretary of war Edwin Stanton. While there was no doubt that Sickles had indeed killed Key, the defense needed to establish that Sickles was justified in this act or perhaps temporarily insane when he fired those bullets. Or both, even.

The prosecution, led by U.S. Deputy Attorney Robert Ould, needed to remind the jury that murder was murder, regardless of the provocation.

DeRose quotes Ould as arguing, “Innovation, even in its wildest moments, has never yet suggested the propriety of allowing revenge, as either justification or even a palliation of the crime of murder. Human society could exist upon no such basis.”

Ould continued, “The common law has the most sacred regard for human rights. So sacred that even the rankest criminal who has assumed unto himself the functions of judge, jury, and executioner, is himself given by that law the privileges of a fair and impartial trial.”

John Graham, presenting the opening statement for the defense, asked the jury to consider what the consequences of adultery should be.

“In this District you have provided no protection against adultery. The inevitable result is, that you are thrown upon the principle of self-defense to protect yourselves and your own. The law tells you…you may take the life of the burglar, but it still permits your house to [be] polluted by the tread of the adulterer,” Graham said, as quoted by DeRose.

Graham advised the jury to “strike terror into the heart of the adulterer” and not to “embolden him in his course.”

On the twentieth and final day of the trial, Ould told the jury that acquitting Sickles “would overturn the principles of common law in regard to murder, and would establish the principle that a man could kill another from motives of revenge.”

Unfortunately, the prosecution failed to sway the jury, which returned with a verdict of “not guilty.” The public, by and large, seemed to side with the jury, and the precedent would last for nearly a century, leading to what eventually became known as the “Unwritten Law.”

“The dam had been building against seducers for years, and now it burst,” DeRose writes. “Sickles forced the conversation into every American living room. What were the consequences of adultery? What were a man’s obligations? The Unwritten Law was announced at Washington City Hall and spread throughout the United States.”

DeRose cites several examples of the Unwritten Law in action, with juries frequently refusing to convict anyone who killed in defense of their family’s honor, ostensibly. Even if the jury did vote to convict, the sentences were often extremely soft, such as one instance where a judge fined the convicted murderer $5, saying, “You are guilty, technically, but I would have done the same thing.”

The Virginia Law Register in 1907 proposed codifying the Unwritten Law because the “constant undermining of the jury oath threatened to shake the foundation of the entire system,” DeRose writes.

The acquittals and light sentences reflected the attitudes of the times, which included neglecting the agency of the women involved in the affairs.

But times changed, eroding the Unwritten Law until murderers could no longer count on its protection. Its final two successful applications occurred in 1954 and 1958, according to DeRose.

DeRose estimates that thousands of people “died under the reign of the Unwritten Law,” though an exact count is virtually impossible, given that many historical newspapers haven’t been preserved and not all cases were covered in the first place.

Star Spangled Scandal is an interesting read, not only for the legal issues discussed above but also for its examination of the role of technology in speeding up communication and increasing the demand for timely and detailed media coverage.

Sickles mania swept the nation in 1859, and that was only with the telegraph. Just imagine if, say, a famous football player was on trial for murder during the age of cable television.