When does a revolution go too far? When other people are considered expendable.

This has happened far too many times throughout history. In the twentieth century, the death toll reached into the millions.

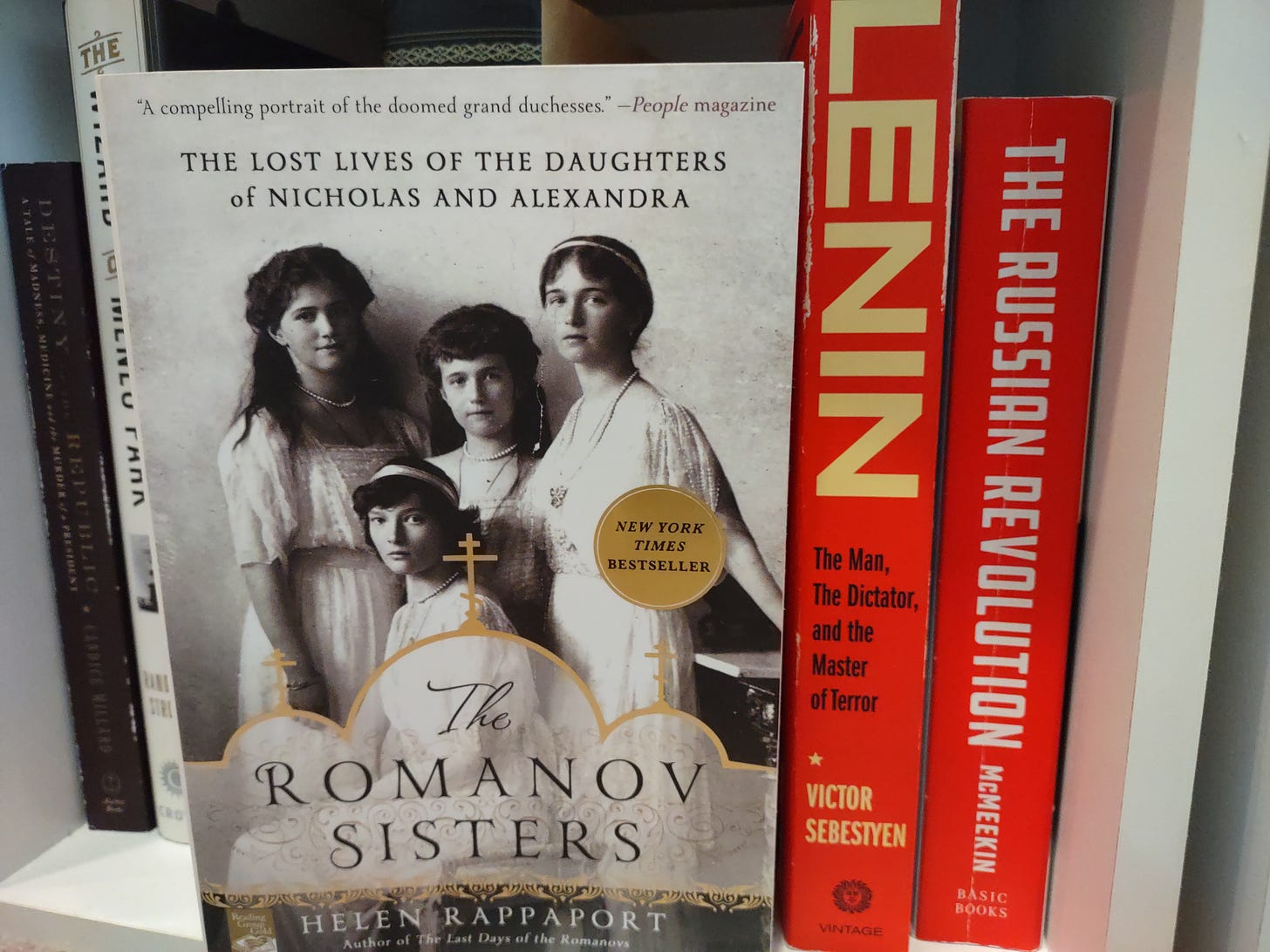

For now, let’s zoom in on just a few of those tragic losses. In The Romanov Sisters: The Lost Lives of the Daughters of Nicholas and Alexandra, Helen Rappaport gives us an up-close-and-personal look at the end of Russia’s Romanov dynasty. Rappaport focuses on the four daughters of the final tsar, Nicholas II, though the parents and son also receive plenty of attention.

Throughout the book, we get to know Olga, Tatiana, Maria, and Anastasia, from birth through their very young deaths. The public often perceived them as virtually interchangeable, but Rappaport presents each as a unique individual.

The oldest, Olga, was 10 in 1905, and Rappaport describes the child as “curious and full of questions” and says that “her flashes of anger revealed a dark side that she sometimes found difficult to control.”

Tatiana at the same time “seemed an extraordinarily self-possessed young girl, but she was in fact emotionally cautious and reserved, like her mother [Alexandra].”

Maria “was the least affected by any sense of her station” and “was the most open-hearted and sincere.”

As for Anastasia, “the youngest Romanov daughter was a force of nature to whose presence it was impossible to remain indifferent,” Rappaport writes.

Rappaport adds that Anastasia “was an impossible pupil; inattentive, always eager to be doing anything other than sit still, yet despite not being academically bright she had an instinctive gift for dealing with people.”

Even before the Russian Revolution, the Romanovs’ world had become more insular. The youngest child, Alexey, the heir apparent, suffered from hemophilia. As the parents strove to protect him, they wound up sheltering all the children, which made them less worldly and perhaps more innocent.

But after Nicholas abdicated in 1917, the family found itself essentially under house arrest in the Alexander Palace at Tsarskoe Selo, without any guarantee of privacy or kindness. Guards roamed the halls, and the public was often peeking into the property.

“The railings of the Alexander Park had now become a public sideshow where people gathered in order to catch a glimpse of the former tsar and his family whenever they emerged in the garden,” Rappaport writes.

Eventually, house arrest in a palace dwindled into house arrest in a two-story house in Tobolsk, further limiting the family’s movement and demoralizing them.

Again, Rappaport zeroes in on the distinct individuals, this time through the perspective of Klavdiya Bitner, a recent addition to the household. Tatiana was the “absolutely linchpin” of the family who was next in line as their “protector” after Alexandra. Olga was “gentle and soft-hearted” while Maria “remained the most self-effacing, her consistently loving and stoical personality inviting the least amount of comment or criticism.” Anastasia played the roles of clown and cheerleader and “kept everyone’s spirits up with her high energy and mimicry.”

And this brings us to the part of the book that stuck with me the most. The Romanovs were again transferred to smaller accommodations and increased supervision. Nicholas and Alexandra were required to depart first, and Maria accompanied them while the other girls remained in Tobolsk to take care of Alexey, who had again become sick.

Eventually, they all had to leave Tobolsk too, and Rappaport describes a local engineer who was at the train station when the four Romanovs were departing, and his recognition of their humanity.

Rappaport quotes the engineer at length, and I think much of it is worth sharing here, as it hammers precisely why you should read this book and others like it:

“I stared at their lively, young, expressive faces somewhat indiscreetly—and during those two or three minutes I learned something that I will not forget until my dying day. I felt that my eyes met those of three unfortunate young women for just a moment and that when they did I reached into the depths of their martyred souls, as it were, and I was overwhelmed by pity for them—me, a confirmed revolutionary. Without expecting it, I sensed that we Russian intellectuals, we who claim to be the precursors and the voice of conscience, were responsible for the undignified ridicule to which the Grand Duchesses were subjected … We do not have the right to forget, nor to forgive ourselves for our passivity and failure to do something for them.”

Rappaport writes, “His natural human instincts had made him want to reach out and acknowledge them, but ‘to my great shame, I held back out of weakness of character, thinking of my position, of my family’.”

Not long after, in 1918, Bolsheviks murdered the entire Romanov family.

Daniel, thank you for that glimpse into the beauty and evil of the 20th century. Our only hope is to wear our humanity as a second skin, not only to protect ourselves, but to save others.