I highly recommend Destiny of the Republic by Candice Millard. The book details how James A. Garfield was elected to the presidency despite not even wanting the job, and how a deranged office seeker shot him, leading to a slow, agonizing death over the course of two and a half months.

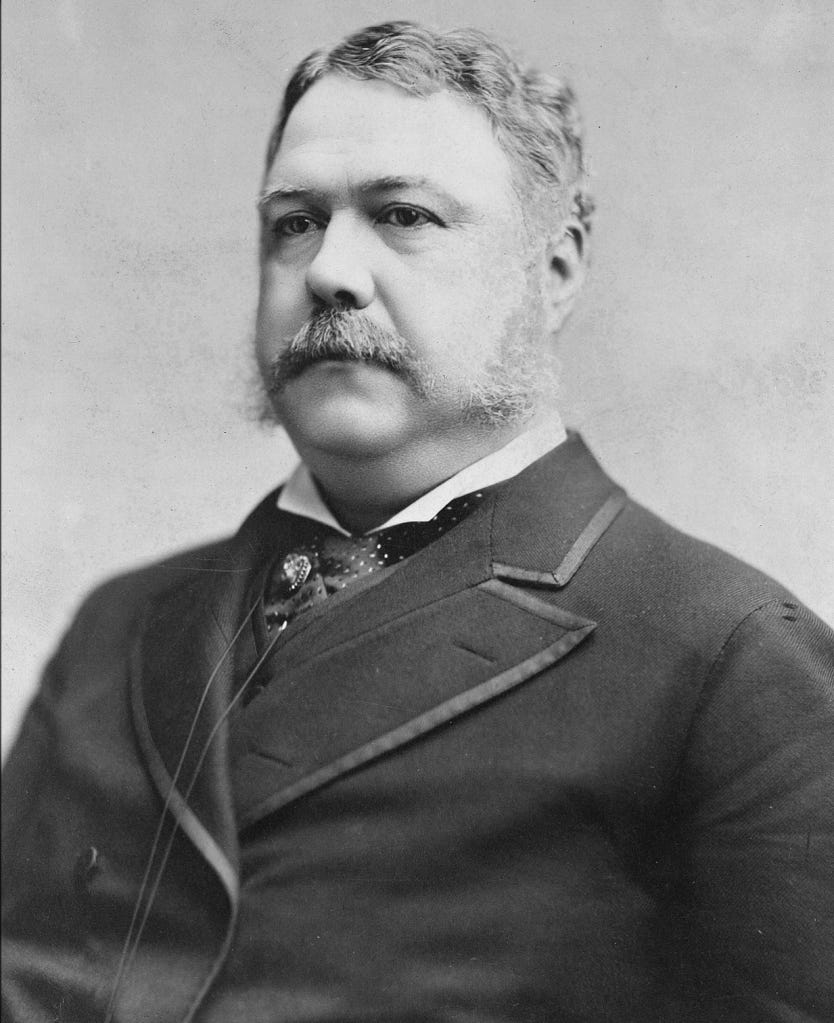

It’s an absolutely fantastic and fascinating book, but here I just want to focus on one thread of the overall story: Chester Arthur’s evolution from reviled political crony to a respected, competent president of the United States.

Chester Arthur is one of those late 19th-century presidents most of us know very little about. And true, he’s not the most remarkable president there ever was. What’s most remarkable about him is how, in defiance of all expectations and his own previous behavior, he managed to rise to the level of decent.

Arthur was nominated as a vice presidential candidate to become a ticket balancer, essentially, and because he would ensure the support of Republican Party boss Roscoe Conkling. Garfield was not consulted on his running mate’s nomination, and indeed, as vice president, Arthur was more loyal to Conkling than to Garfield.

Before becoming VP, Arthur’s only political appointment was as a collector of the New York Customs House. Conkling secured the position, which carried a hefty salary. According to Millard, Arthur seldom arrived at work before noon, and the future President of the United States left the position in the wake of corruption allegations.

Millard quotes an unnamed man, speaking to a reporter, who captured the general sentiment felt toward Arthur: “Gen. Arthur appears as a politician of the most ordinary character, a man whose sole thought is of political patronage, and a man who has for his bosom friends and intimate companions those with whom no gentleman should associate.”

So, after Garfield was shot, people were understandably apprehensive about the increasingly likely prospect of a President Chet Arthur. Arthur himself seemed to be as apprehensive as anyone, and he kept out of sight while doctors were desperately trying to save Garfield’s life. He didn’t want to be seen as usurping the presidency while the president still lived.

But eventually he would have to come out of hiding and face reality, and he received his most important encouragement from a total stranger.

Julia Sand, whom Millard describes as a 32-year-old unmarried invalid, reached out to Arthur and appealed to his better nature in a series of letters. Arthur kept 23 of the letters she sent him.

“The hours of Garfield’s life are numbered—before this meets your eye, you may be President. The day he was shot, the thought rose in a thousand minds that you might be the instigator of the foul act. Is not that a humiliation which cuts deeper than any bullet can pierce?” Sand wrote in her first letter.

“Your kindest opponents will say: ‘Arthur will try to do right’—adding gloomily—‘He won’t succeed, though—making a man President cannot change him.’ But making a man President can change him! Great emergencies awaken generous traits which have lain dormant half a life. If there is a spark of true nobility in you, now is the occasion to let it shine. Faith in your better nature forces me tow right to you—not to beg you to resign. Do what is more difficult & more brave. Reform!”

Sand also wrote, “It is not the proof of highest goodness never to have done, but it is a proof of it… to recognize the evil, to turn resolutely against it.”

Arthur heeded her advice, and he strove to be the sort of president Garfield would have. While Arthur was never going to be a great man, he succeeded in winning over the critics who were dreading his presidency.

Arthur McClure, a journalist of the era, wrote, “No man ever entered the Presidency so profoundly and widely distrusted, and no one ever retired… more generally respected.”

Even Mark Twain himself commented, “I am but one in 55,000,000; still, in the opinion of this one-fifty-five millionth of the country’s population, it would be hard to better President Arthur’s Administration.”

A stranger’s unsolicited compassion and faith helped save Arthur from himself, and helped save the country from a few years of an inept, shallow president. It’s something to keep in mind whenever we’re tempted to write someone off as irredeemable.

Daniel Sherrier is a writer living in central Virginia. A William & Mary graduate, he worked for community newspapers for nearly a decade as a reporter and then an editor. He is the author of the superhero novels The Flying Woman and The Silver Stranger, and he overthinks stories and writing on his own Substack. He is NOT a historian, but loves reading about history and sharing interesting books.