The Graciousness of Grant

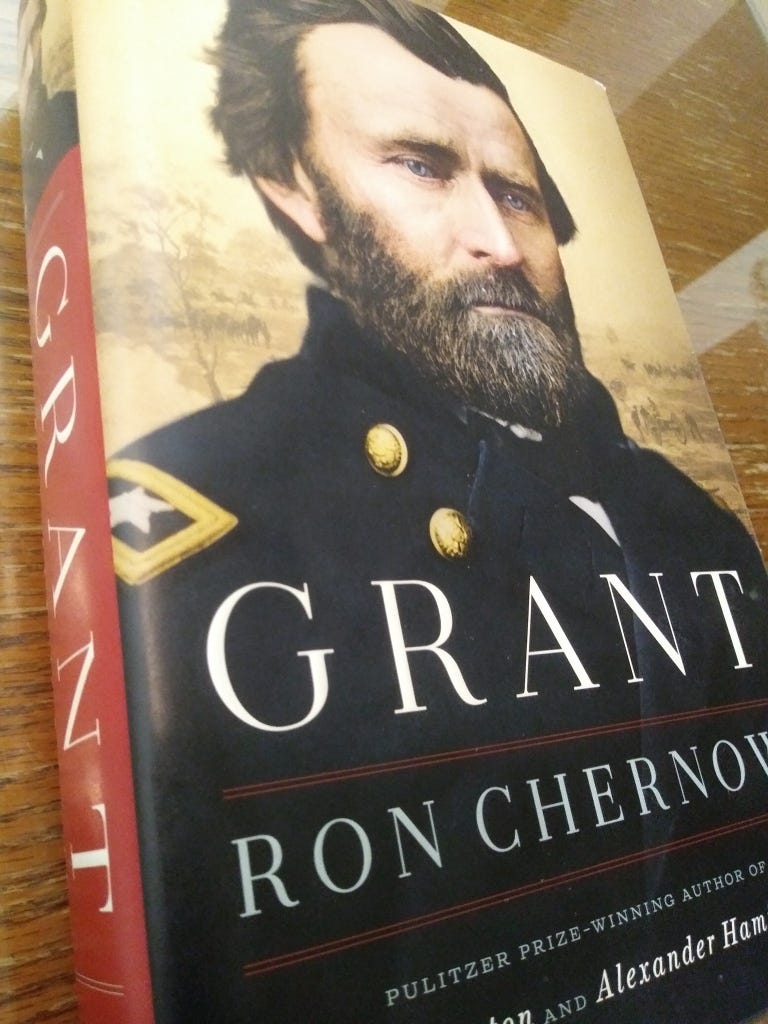

A Look at Ron Chernow's Biography of the Civil War General and President

The surrender at Appomattox has the ingredients for a great one-act play.

The two leads are perfect foils. The defeated general, a living legend to his men, is fifteen years older and held a much higher rank than the victorious general the last time they met, many years earlier (an encounter the older man doesn’t even remember). The victorious general, a failure in civilian life, shows up in “rough garb,” by his own admission, in sharp contrast to the defeated general’s polished ceremonial attire.

The victorious general begins with friendly chitchat, to which the defeated general responds cordially. But the defeated general can’t hide his grave demeanor; the fate of his men depends on this rough-hewn, middle-aged failure sitting across from him. Will he be vengeful? Will he push for punitive measures against the Southern army? Or will he show mercy?

Fortunately, General Ulysses S. Grant chose to be merciful and kind to Robert E. Lee and his army. Without excusing the Confederacy’s wrongdoings, Grant was able to emphasize with his opponents and remember their humanity.

Grant later wrote in his memoirs, “I felt like anything rather than rejoicing at the downfall of a foe who had fought so long and valiantly, and had suffered so much for a cause, though that cause was, I believe, one of the worst for which a people ever fought, and one for which there was the least excuse.”

As Ron Chernow describes in his superb biography, Grant, the Union general came prepared with terms, but he drafted the specific language on the spot. “Grant trusted to the moment’s inspiration,” Chernow writes.

The terms included the following: “The Arms, Artillery and public property to be parked and stacked and turned over to the officer appointed by me to receive them…This done each officer and man will be allowed to return to their homes not be disturbed by United States Authority so long as they observe their parole and the laws in force where they may reside.”

The U.S. government would have been within its rights to charge Confederate soldiers with treason and put the recovering nation through a lengthy series of trials. But that would not have facilitated healing, nor would it have moved the country forward.

Chernow notes that Grant chose not to ask Lee to surrender his sword. It wasn’t just to avoid making a martyr of the man; Grant also didn’t want to humiliate him.

“With no tinge of malice, Grant’s words breathed a spirit of charity reminiscent of Lincoln’s second inaugural address,” Chernow says.

Lee accepted the terms with only minor revisions. “It is more than I expected,” he said.

Grant also arranged to provide food for Lee’s hungry troops.

“Grant showed genuine compassion for the Confederate soldiers, saying he assumed most were farmers and wanted to plant crops to tide them over during the winter. To this end, he issued a directive that rebel soldiers who owned their horses or mules should be allowed to take them home,” Chernow writes.

Chernow also notes how pleasantly surprised the Confederate troops were, as many were expecting punitive measures from Grant. Chernow quotes an unnamed soldier as having said, “The favorable and entirely unexpected terms of surrender wonderfully restored our souls.”

To avoid wounding the Southerners’ pride, Grant even halted the celebrations of his own men while both armies were still in the area.

James Longstreet, a Confederate general, visited Grant at Appomattox. Grant offered him a cigar, and they renewed their friendship over a card game they used to play.

According to Chernow, Longstreet said, “Great God, thought I to myself, how my heart swells out to such a magnanimous touch of humanity! Why do men fight who were born to be brothers?…His whole greeting and conduct toward us was as though nothing had ever happened to mar our pleasant relations.”

“Grant’s courtesy at Appomattox became engraved in national memory, offering hope after years of unspeakable bloodshed that peace, civility, and fraternal relations would be restored. It was a fleeting, if in many ways doomed, hope, which may be why it has had such staying power in the American imagination,” Chernow writes.

And true, Grant’s good manners did not foreshadow a smooth Reconstruction period, and that’s one of history’s many tragedies. But Grant behaved exactly right on April 9, 1865, showing us how to treat our defeated enemies as friends, and how forgiveness is more important than punishment.

“Such was Lee’s unrivaled stature that his acceptance of defeat reconciled many diehard rebels to follow his example. At the same time, it was Grant who set the stage for Lee’s high-minded behavior by treating him tactfully, refusing to humiliate him, and granting him generous terms that allowed him to save face in defeat,” Chernow says.

The surrender could indeed make a great play, one that combines aspirational ideals with tragic undercurrents.

Daniel Sherrier is a writer living in central Virginia. A William & Mary graduate, he worked for community newspapers for nearly a decade as a reporter and then an editor. He is the author of the superhero novels The Flying Woman and The Silver Stranger, and he overthinks stories and writing on his own Substack. He is NOT a historian, but loves reading about history and sharing interesting books.