We tend to think of the Civil War as the American war that pit families against each other. But not every resident of the thirteen colonies favored American independence during the Revolutionary War. Even Benjamin Franklin’s own son, the royal governor of New Jersey, opposed breaking ties with the crown.

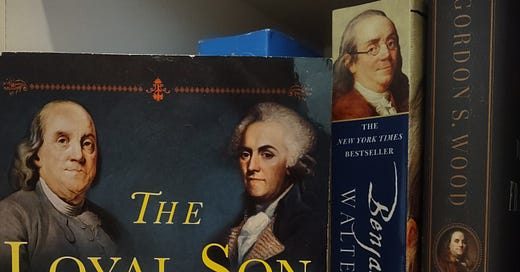

Daniel Mark Epstein examines the relationship between father and son in his fascinating book, The Loyal Son: The War in Ben Franklin’s House.

The book is a sort of dual biography tracking the lives of Benjamin Franklin and his illegitimate son, William Franklin. Epstein focuses on the relationship between the two, showing us how close father and son were in earlier years and how the American Revolution destroyed their relationship.

Having read other books on Ben Franklin and the American Revolution, the fresher and more interesting parts for me were those that focused on William. As a prominent Loyalist, William Franklin provides a lens through which to view the losing side of the conflict. History may be written by the winners, but we should still seek to understand those who didn’t win, even if we continue to disagree with them.

With Benjamin and William both being public figures, they acquired their share of enemies over the years. According to Epstein, cynics of the era imagined self-serving reasons for the father to side with independence and the son to side with the Crown—whichever way things went, the winning Franklin would be able to help the losing Franklin restore his reputation and livelihood.

Epstein doesn’t subscribe to that theory, and he explains how Ben Franklin felt he had to cut off communication with his son to ensure he remained an unassailable advocate for American independence. They both maintained contact with other family members, and the strongest connection between Ben and William was William’s own illegitimate son, Temple Franklin, whom Ben adored and took under his wing.

While Ben was in Paris advocating for a new nation, William was getting himself into further trouble. After the royal governor was arrested, William was placed on parole, but then he was caught issuing pardons on behalf of the Crown. This irritated George Washington, who had known and previously gotten along with William and his wife Elizabeth, and it led to a downright medieval imprisonment for William Franklin.

Epstein describes Franklin’s entry into his cell in Litchfield:

“It smelled awful. The turnkey showed him the cell, and he might have thought this was a joke or a ruse to frighten him on his first night in the patriot outpost. The room was empty except for a stoneware chamber pot. The plank wood floor was strewn with straw. In the twilight from the high little window the prisoner searched the four corners in vain for a chair to sit in or a pallet to lie upon.”

For six months, William Franklin was not permitted to step foot outside this dismal cell, and he was not permitted to speak with anyone.

“The jailers were not inhuman, but they had orders not to converse with the wily Tory,” Epstein writes.

He quotes William Franklin as saying, “I was in a manner excluded human society, having little more connection with mankind than if I had been buried alive.”

The conditions took a toll on his health, and through letters slipped under the door, he learned that his wife’s health was also declining. Elizabeth Franklin was not expected to recover.

William Franklin wrote a letter to Washington, pleading to see his wife one last time and appealing to the general’s humanity. Epstein calls the letter “a superb work.”

“The letter, more than twelve hundred words, might have melted a heart of iron, not to mention the fellow-feeling of George Washington, known for compassion, and one who had visited this man and his wife in their home in a time of peace.”

Epstein notes that William invoked his father in this letter, quite possibly the only time he ever did so.

“… I trust and believe that though we differ in our political sentiments, yet it has not lessened his natural affection for me, any more than it has mine for him, which I can truly say is as great as ever,” Franklin wrote to Washington.

Washington was inclined to grant the request, if he could have. But he believed only congress had the authority to do so. He wrote to John Hancock, president of congress, advocating on William Franklin’s behalf.

Congress denied the request and enclosed a copy of a pardon endorsed by William to justify their decision. Elizabeth, at 43, died the same day Congress denied William’s request to see her.

As usual, there’s much more to the book than what I’ve described and quoted above, such as William’s efforts on behalf of the Loyalist cause after he left Litchfield. So, read the whole thing, and I’ll leave you with these wise words from William’s sister, Sarah “Sally” Franklin Bache. Writing to her nephew Temple, she said:

“I care not into what hands this letter falls, nor who sees it for I should despise the person who could not make the distinction between a political difference and a family one.”