The Enemy of my Enemy Is Not a Trustworthy Friend

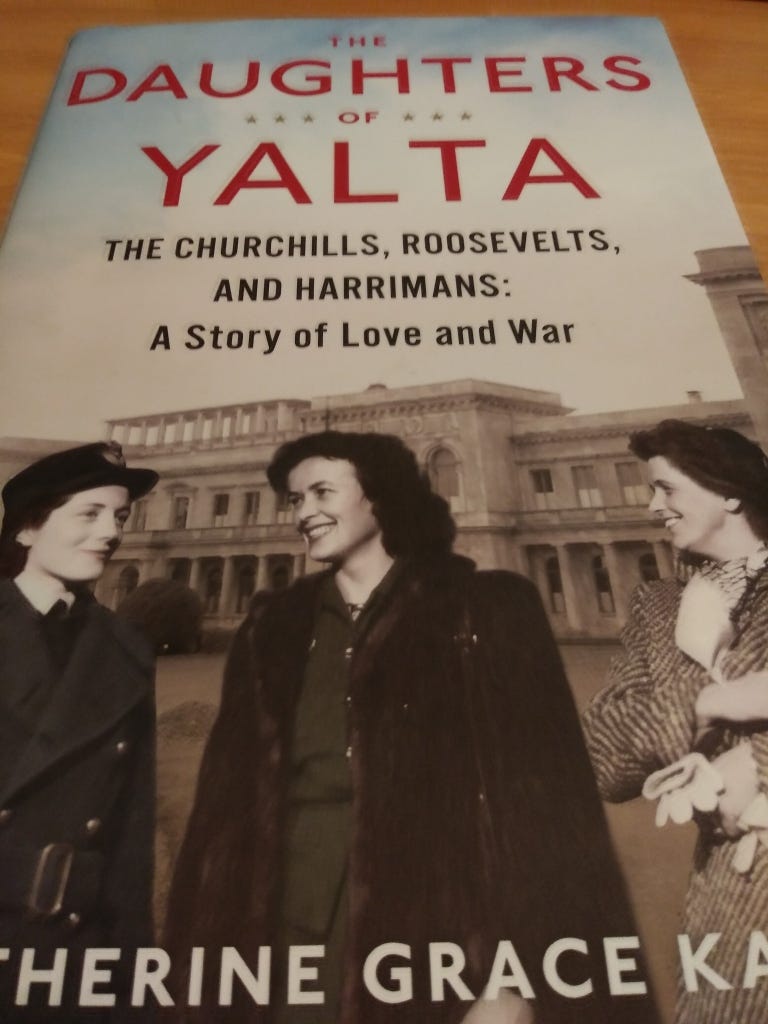

History is more interesting with additional points of view, and that’s what The Daughters of Yalta accomplishes.

Written by Catherine Grace Katz, the book recounts the Yalta Conference from the perspectives of three eminent daughters: Sarah Churchill, Winston Churchill’s favorite child; Anna Roosevelt, FDR’s daughter who was tasked with guarding the secret of the president’s ailing health; and Kathleen Harriman, daughter and most trusted confidante of U.S. ambassador Averell Harriman.

Their inclusion adds greater depth to the history, and Katz does an excellent job of getting inside everyone’s heads, fathers and daughters alike, to present the personal dimension. For example, we get a sense of how Winston was haunted by Europe’s failure to achieve a lasting peace after the previous World War.

The book also shows the friction within the U.S.-British-Soviet alliance, and how the Soviets were generating the bulk of that friction. The Americans and British were indeed swimming with sharks to defeat the Nazis (sharks who were previously allied with the Nazis, who of course could also be described as sharks themselves).

On one hand, the Soviets showed excessive hospitality at Yalta. Their guests’ most casual wishes were granted. Sarah Churchill mentioned how lemon would go nicely with the caviar she was eating, and wouldn’t you know it, a lemon tree appeared on the premises the next day.

But the wish-granting had a dark side. The Soviets were spying on the Americans and British. They planted non-metallic bugs and installed microphones to eavesdrop on their guests.

“They steered FDR toward their listening devices in the Livadia gardens by tidying certain garden paths, so he could manage them in his wheelchair, practically guaranteeing that they could follow his every move,” Katz writes.

Soviets would transcribe private conversations and report summaries to Stalin in advance of meetings.

The NKVD secret police were an ominous presence at the conference. Katz explains that they were “an elite force of terror under Stalin’s leadership. The agency became the secret police and assassination squad. It made the supposed enemies of the people, whether political dissidents or an entire ethnic minority, disappear.”

Kathy Harriman had already learned to be suspicious of the Soviet government, and she was not alone in her concerns. Working as a newspaper reporter in London, she was tasked with covering press conferences given by leaders of exiled European governments, such as those of Poland and Czechoslovakia.

“At these press conferences, the issue that raised the most immediate concern was not Nazi aggression, but rather Britain’s new alliance with the Soviet Union. The exiles were not pleased with the sudden rush of support for Stalin in Britain and the United States,” Katz writes.

“The exiled Polish leaders were particularly vocal. They argued that Stalin would look for any opportunity to seize Poland and install a de facto Soviet regime. Kathy believed them. Not until the late summer of 1944 would Averell realize that Kathy had been right to listen.”

Even before the conference, Kathy Harriman experienced the Soviets’ duplicity firsthand, though she didn’t realize it until later. She and several other journalists were invited to Katyn Forest in Russia to observe a mass grave containing the remains of thousands of Polish soldiers.

What had actually happened was that the Soviets executed nearly 22,000 Polish citizens in 1939. This included “soldiers, intellectuals, and aristocrats — anyone who might have the means and desire to actively resist Soviet rule,” Katz writes.

“With so many ‘enemies of the state’ in their clutches, the Soviet leaders realized they had a prime opportunity. They could begin liquidating the Polish ruling class, thus making it easier to control the country once the war was over.”

Stalin ordered the executions, and the Soviet agents tampered with the evidence to make it look like the Nazis committed the massacre. The Soviets then fooled the journalists, including the skeptical Kathy Harriman, into believing their innocence regarding this particular atrocity.

“The Nazis committed countless crimes against humanity … but the Katyn Forest massacre was one crime they did not commit,” Katz says.

She later adds, “No matter how much the British and the Americans abhorred the atrocities the Soviets committed, defeating the Nazis remained paramount.”

The Daughters of Yalta is an excellent, insightful book. I’ve provided only a glimpse of it. Read the whole the thing!

Daniel Sherrier is a writer living in central Virginia. A William & Mary graduate, he worked for community newspapers for nearly a decade as a reporter and then an editor. He is the author of the superhero novels The Flying Woman and The Silver Stranger, and he overthinks stories and writing on his own Substack. He is NOT a historian, but loves reading about history and sharing interesting books.