Taken Together: "The Wild Truth" of "Into the Wild"

Reviving an old series with two glimpses into the short, tragic life of outdoorsman Chris McCandless

It's spring! Finally! Where I live, that means camping season at Joshua Tree National Park, especially right now, in between the weekends of the Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival.

I haven't been tempted to go to the concerts - I hate crowds - but despite my girliness, I wouldn't mind joining in with the camping! It’s likely a bad call due to the injury in my arm, but I've always found being in the wilderness electrifying: frightening, fantastical, and freeing in equal measure.

So it makes sense that I'd seek out survival stories of others who have ventured into the wild - intentionally or by accident - with little more than their wits. And one story I absorbed with sadness and confusion was that of Chris McCandless, who was attempting to live off the land in Alaska’s interior back in 1992, but died at the unfortunate age of 24, apparently having succumbed to starvation.

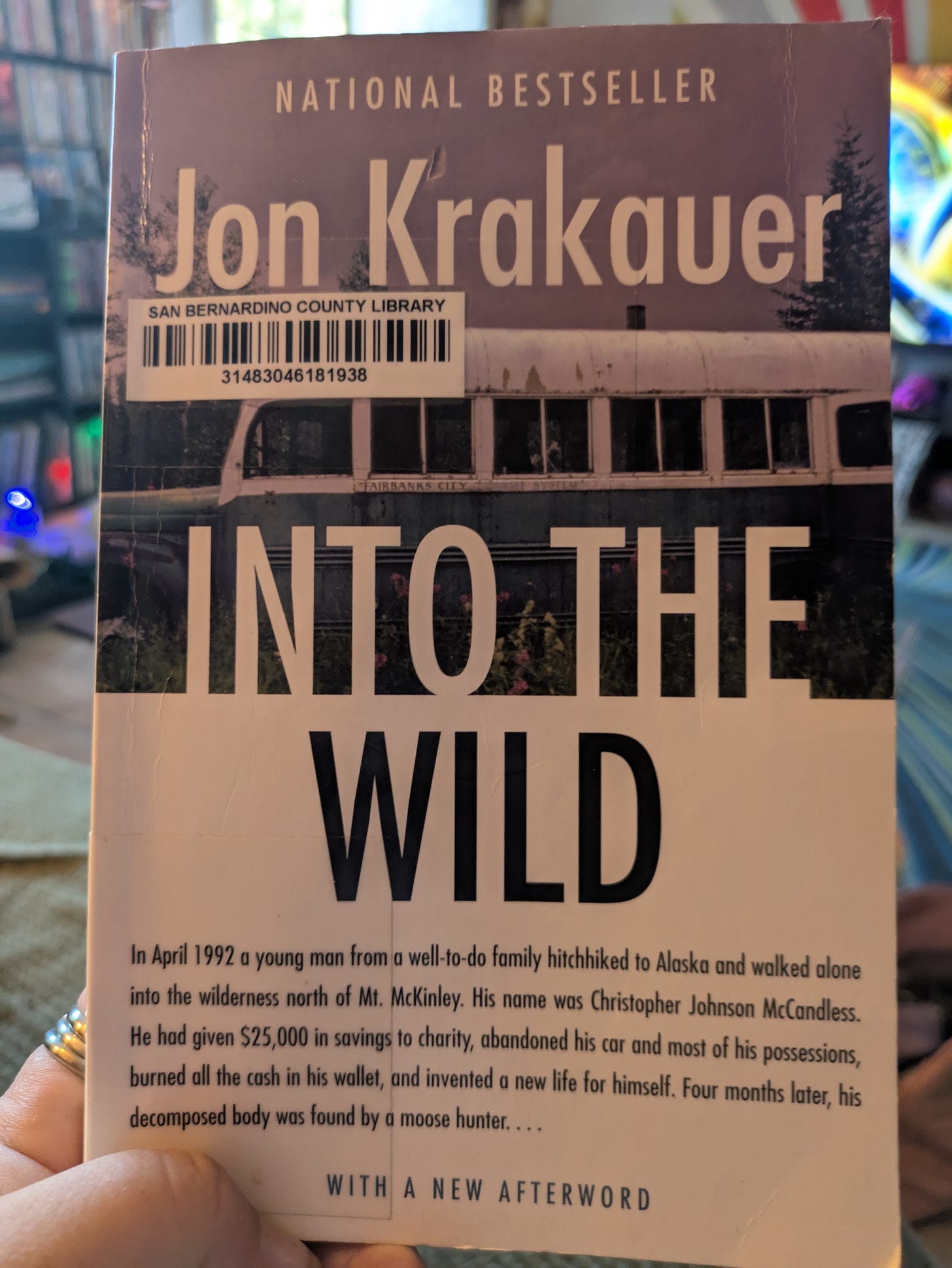

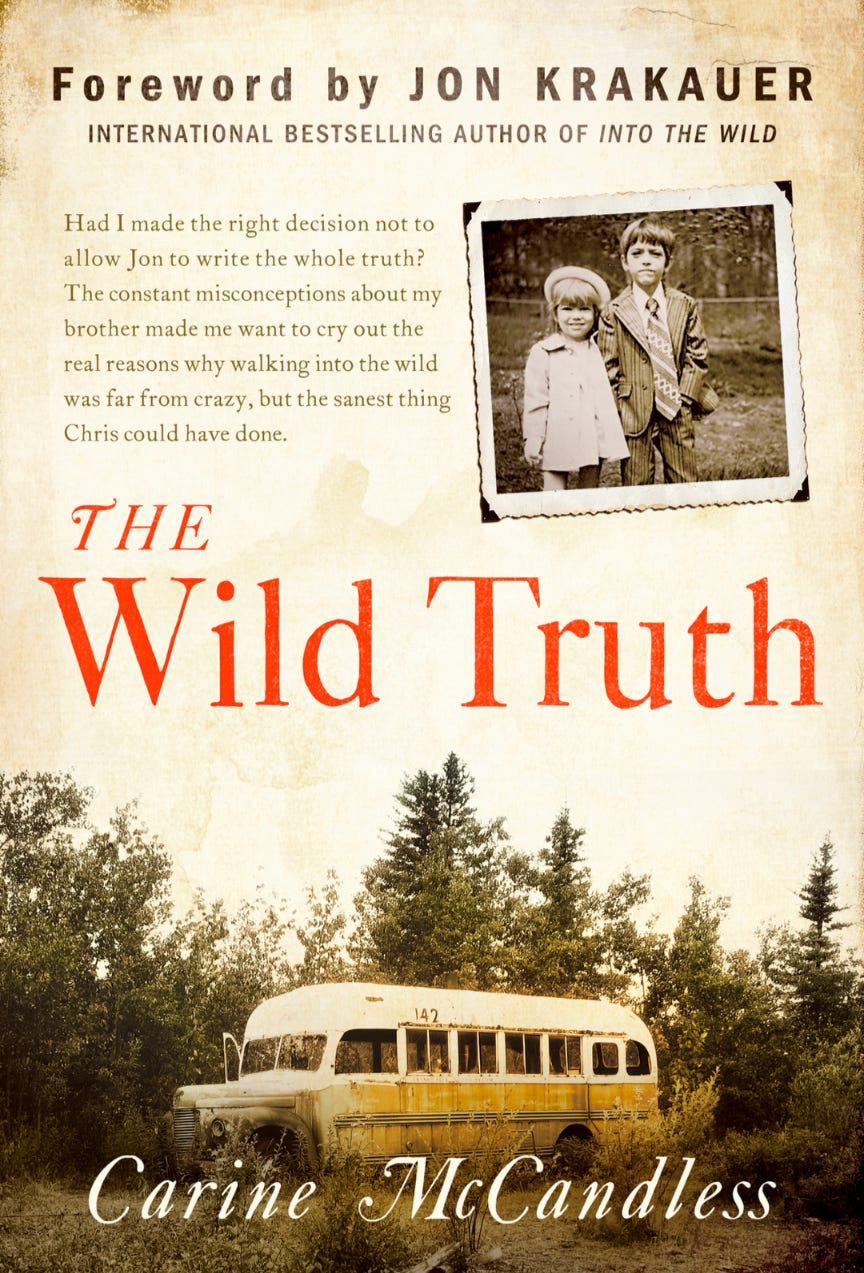

In this study, I'm considering two books that describe Chris’ ordeal and situate what happened within clarifying context of his life: 1997’s “Into the Wild,” by Jon Krakauer and 2014’s “The Wild Truth,” by Carine McCandless, Chris’ adored younger sister.

You've probably heard at least some of this: By all accounts, Chris - or “Alexander Supertramp,” as he introduced himself on his journeys, wishing to break away from his family - was a terribly earnest and idealistic young man. News articles shrieked that Chris had donated the remains of his college account to OXFAM - $25,000 in 1990; $62,570 in 2025 - before heading out on his odyssey, a move unthinkable to most.

And indeed, Chris shunned his wealthy upbringing. Obsessed with the ideas of Henry David Thoreau, Leo Tolstoy, Jack London, and Walt Whitman, he was deeply concerned with living a life of authenticity, self-reliance, and a kind of nirvana achievable only by combining those principles with communion in nature. He set out on a strict, self-designed quest to find true happiness in simplicity and solitude.

He did find it, but only briefly: Chris’ wits appeared not to be enough to sustain him, and he actively refused to take sensible precautions - for instance, he didn't even have weatherproof boots for Alaska until the concerned gentleman he hitchhiked with gave Chris his own spares, which happened to be in the back of his truck.

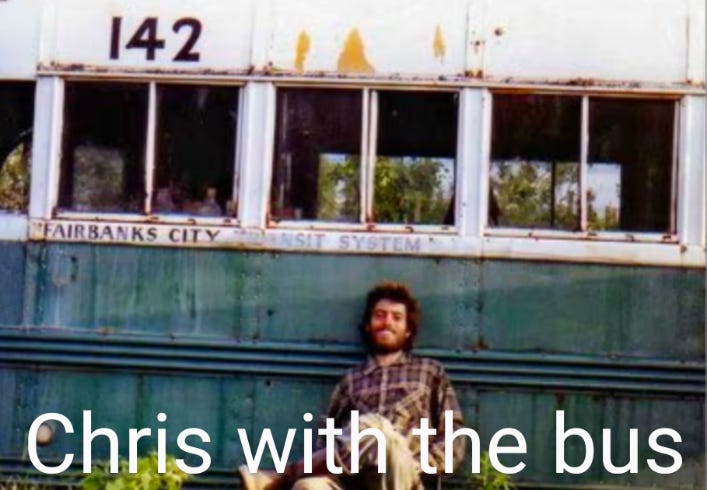

But good boots weren't enough. His remains were discovered by hikers in September of 1992, inside a 30-year-old decommissioned city bus (“Fairbanks 142") that had once served as laborers’ quarters before their project was scrapped. He'd been dead for two and a half weeks. The log he kept spoke of difficulty finding game. His remains were reduced to only 66 pounds, and it was inferred that Chris had starved to death.

In America, we hear of lots of young adventurers with more moxie than maturity who die in the outdoors, be they Jack London disciples, maladjusted youths, or young men who simply yearn to have been born in a time when maps were still blank in places. But Chris was different - for a few reasons.

Chris McCandless had been successfully “tramping"- his term - as Alexander Supertramp, or just Alex, for more than two years when he left the Mojave Desert for South Dakota, then Alaska. He lived outdoors, hitchhiked, rode the rails: It was a lifestyle few of us choose, but he loved every minute, and he was making it work. Chris was known to be physically strong, capable, and intelligent. Those he met on his perambulations were, to a one, left with the strong impression of a deeply idealistic and brilliant young man.

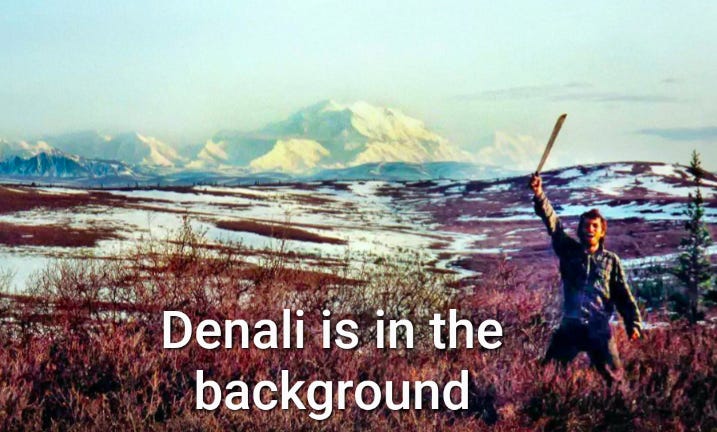

Chris was also a faithful diarist, leaving a poignant makeshift journal, five rolls of film filled with absolutely arresting photography (including every image of him displayed in this article), and even video footage that chronicled the triumph and tragedy of his 113 days in the Alaskan bush.

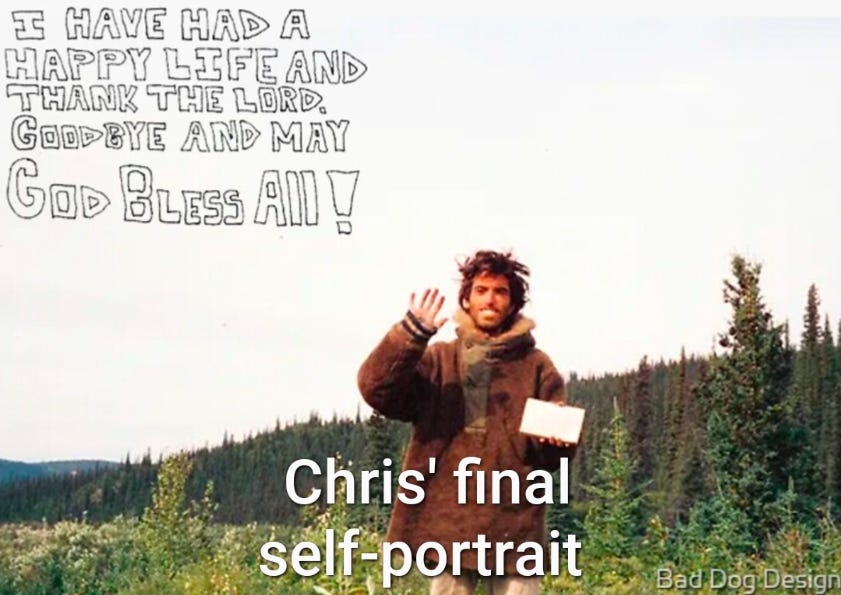

The part of this story that first pulled at the heartstrings - well, aside from his age, his philosophizing, his determination to live in hardship, his frankly gorgeous smile, and the impressions he made on everyone he met - was the gut shot of a note he left behind, to no avail, on the door of that bus in Alaska that would be his coffin:

“Attention Possible Visitors. S.O.S. I need your help. I am injured, near death, and too weak to hike out. I am all alone, this is no joke. In the name of God, please remain to save me. I am out collecting berries close by and shall return this evening. Thank you, Chris McCandless. August ?”

But there was one other part of the story that captured the public imagination, too. It was reported that McCandless had a loving family of origin he refused to contact. His wealthy parents, who ran an aerospace consulting concern in the DC area, had given him a privileged upbringing, and by way of thanks, he had thrown it all away - including his own life, it seemed. When McCandless died, his parents and siblings had no idea where he was. They had not seen him or heard from him or in more than two years: not since his college graduation.

His death was eloquently reported in the New York Times and subsequently covered in Outside magazine in an 8,400-word treatment by Jon Krakauer, noted mountain climber, outdoorsman par excellence, and increasingly distinguished writer. His beautiful story inspired more letters to the editor than any other piece in the magazine's history, with most of the feedback casting Chris as an incompetent greenhorn who was out of his league in Alaska from Day One.

But Krakauer believed there was much more to the story. Accordingly, he spent years retracing Chris’ steps; working with the McCandless family and the friends Chris had made on the road to turn the upsetting saga into a surprise runaway best-seller: “Into the Wild.” Ten years later, Sean Penn turned the book into a 2007 film of the same name, which started Emile Hirsch as Chris and Jena Malone as Carine McCandless, Chris’ adored younger sister.

While it's through Krakauer's years of tireless research that we know as much as we do of Chris’ life and “tramping" from 1990 to his death, it was Carine who got readers to care about a book-length treatment.

She was far and away the most valuable provider of insight into her brother's life, character, and motivations for both projects. For it turned out that Krakauer was exactly right to suspect that there was more - much more - to Chris’ story. After a lengthy deliberation, and only upon extracting a promise that Krakauer would merely hint obliquely at, and not clearly state what she was about to disclose to him, Carine McCandless filled in for the author the background and context that was sorely missing - indeed, necessary to properly understand what had happened.

Krakauer kept his promise. Penn did, too, though he was allowed to reveal somewhat more for the film. Carine McCandless surely breathed a sigh of relief. The book gave the impression that Chris, an intense fellow, had often clashed with his equally intense father, and that this was too bad - a sad thing to have happen. Readers assumed it was this dynamic that had sent Chris, well, into the wild fueled by a fit of pique he could or should have gotten over long ago.

“Adolescent rage," people clucked sympathetically to Chris’ parents, Walt and Billie McCandless. "To disown his whole family; to not even try to save his own life! I guess he just never grew out of it.” Walt and Billie nodded sadly and basked in strangers’ sympathies, while Carine felt both guilty and annoyed with herself for obscuring the truth.

Secrets, she realized, only have power when they're kept in the dark. As the book “Into the Wild” became required reading at high schools all over the country and the film passed firmly into the Outdoor/Survival canon, Carine McCandless came to feel that it was time to clear things up.

In 2024, out came a memoir: “The Wild Truth,” and with it, several revelations that change not just its main character, who was clearly neither crazy nor arrogant nor on a suicide mission, but the entire story around him.

In “The Wild Truth," Carine McCandless summarily dismantles the prevailing wisdom and builds a new understanding of this tragic life lost too early, one nugget at a time.

**********************************************************

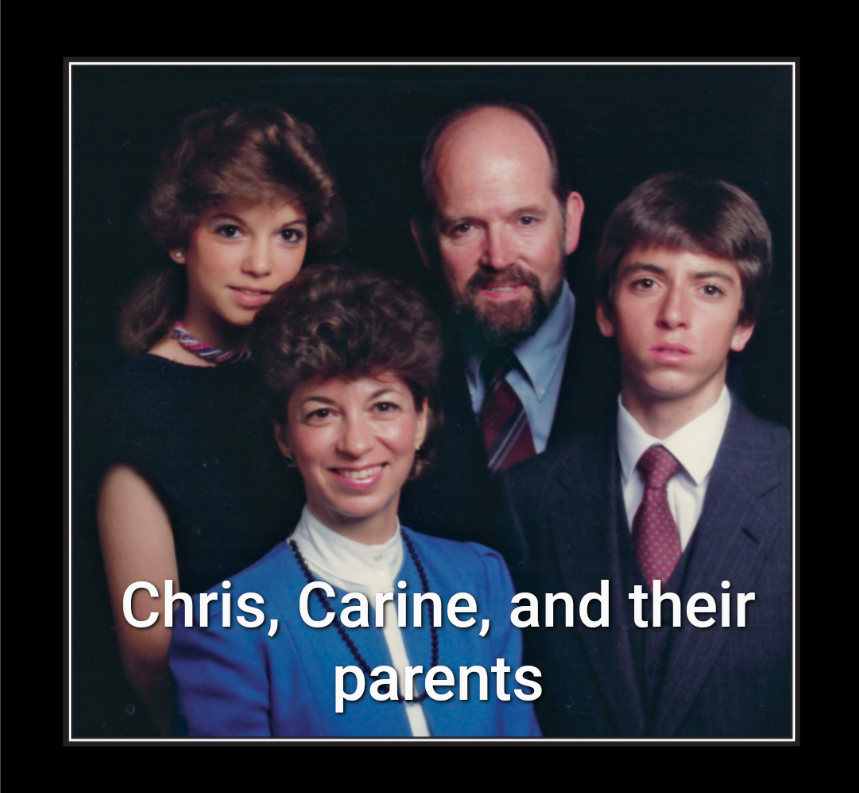

Carine starts at the very beginning: Her mother, Billie, became pregnant with Chris at a time when Walt was still married to his first wife. And not just “still married:" He was still living with his first family. Talking out both sides of his mouth, he swore to Billie that he'd leave Marcia, and to Marcia, he vowed he'd never go.

As Billie, his much younger mistress (who believed she was her boyfriend's only partner), became visibly pregnant with Chris, Walt McCandless began to maintain two residences, lying to both women. He'd spend two weeks at one house and two weeks at another, claiming that he was traveling for business when he was gone.

This allowed him to impregnate both Marcia and Billie simultaneously, and they were left to put the pieces together. It was terribly stressful, and Walt began to bark at Billie - and then started knocking her around. He also, as the euphemism goes, began to "insist on sex” with her, and so Carine was conceived three years later, with no change in their marital status. Mortified, Billie dragged him to a portrait studio, had their picture made - without the kids - and sent it in with a “Recently Wed" announcement to her hometown paper in Michigan.

Walt had begun to suggest to his first wife that perhaps a split was in order, but she beat him to it, filing for divorce and moving her six children - some of them no more than three months apart in age from Chris or Carine - back home to Colorado. Walt saw a career opportunity, so he married Billie and moved his new family to the Washington, DC area to further his career in aeronautics.

But that timeline was wildly obscured in the Krakauer story and book, as well as whenever Walt and Billie spoke about their family. For a time, Walt even claimed his youngest child with Marcia wasn't his, hilariously implying that Marcia had a lot of time to date as the single mother of five young children.

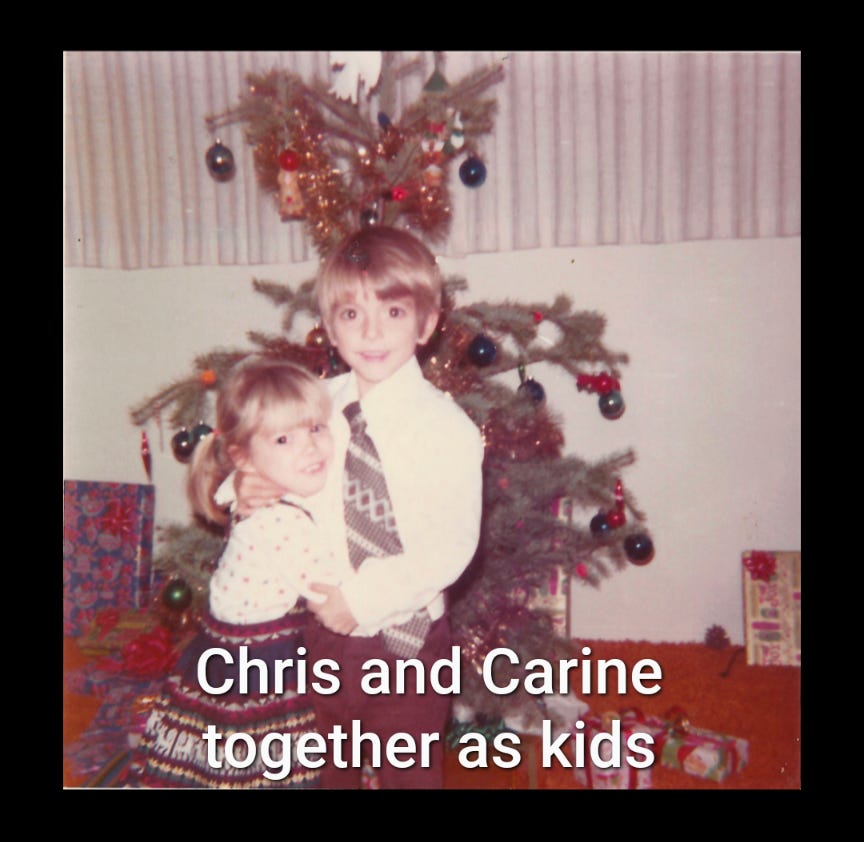

So Carine set the record straight. The next point she needed to make: Both Walt and Billie were addicted to various substances during her childhood, and they were both physically and emotionally abusive to Chris and Carine growing up: breathtakingly so. Though it's in the book, such evil does not need to be detailed here. Trust, however, that it was awful. As the McCandless’ wealth increased from the consulting firm they somehow held down, so did their violence against their children - and each other, with the result that Chris was Carine's protector: her safe place and her courage.

By the kids’ adolescence, it was clear that Walt and Billie loathed each other, yet stayed together - not to mention that they continued to run a successful business together, somehow - in a deeply enmeshed and violent codependence. Sure, they strung together enough camping trips and vacations, big Christmases and trips to Colorado to see their six half-siblings, Marcia's children - to keep up appearances and let their children enjoy the fruits of their labors. They attended church faithfully and were thought of as pillars of the community. But Chris and Carine’s childhoods were a claustrophobic contradiction that filled Chris, three years older than Carine, with doubt about who he could trust and what truth even was.

But Carine explains that one of the biggest blows came during the summer between high school and college. Chris was planning a summer-long road trip in his beloved yellow Datsun. The young man decided to go west: all the way west. He ended up in the El Segundo subdivision where he'd grown up. An intense kid but gregarious when he wanted to be, he dropped in on some former neighbors and acquaintances, asking what they remembered about his family.

It was during this trip that he learned of the, er, overlap between Walt's marriage to Marcia and his relationship with Billie. He had begun to wonder about the timeline of the eight McCandless children's births, which his parents had intentionally obscured, and this was the exact information he needed.

Learning of this deep ethical failure - which, crucially, he saw Billie as complicit in, not as a victim of - imbued Chris with a deep sense of disgust with his parents. Walt and Billie were hypocrites, Chris decided, hiding their sins behind church attendance and their horrific, abusive parenting behind money and the veneer of success.

Carine elucidates this so well because she was the only one Chris confided in. He never confronted Walt and Billie about their misdeeds, past or present - he never brought it up at all. But his takeaway was that Walt had been “a bigamist.” Any respect he might have had for his dad's intelligence or his work ethic; any fondness he might have held for happier times with his parents absolutely cratered in the wake of Chris’ California discoveries.

During college, he began to distance himself from Walt and Billie even more. After he finished, Chris had just plain had it. Carine explains that Chris made it through college at Emory University in Georgia with excellent grades, continuing to take lengthy road trips out west during his semester breaks. At school, he lived off-campus in spartan conditions. As a way of breaking from Walt and Billie’s bullying, he didn't even keep a phone line; as a result, his younger sister has a treasure trove of letters from her brother during this time, when his philosophy of scarcity of physical comforts and spontaneity of movement as architects of personal character took shape.

It's easy for kids who grow up well-off to eschew their parents’ seemingly insulated lifestyles, refusing to acknowledge, let alone appreciate the hard work and good stewardship of resources that provided that comfort. But Carine shows us that Chris was serious. At graduation, he refused his parents’ offer of a new car (fuming again, in a letter to Carine, that they were “hypocrites"), and mumbled something parent-pleasing about maybe going to law school. He said he had a lot of options, though, and implied he'd be back to visit his parents in Annandale before making any major moves.

But that wasn't what happened.

Instead, Chris wrote a check to OXFAM America for the remainder of his college fund, let his family assume he was still living in his phone-less apartment, and instructed the post office to hold his mail. This gave him a head start, he lit out for California with only enough cash to gas up his car. Soon, after the car got stranded in a desert wash, he actually burned the cash he had and began to move around on foot and by hitchhiking.

In Krakauer’s book, it is detailed that Chris spent two years moving back and forth through California, Arizona, and South Dakota, working here and there, at a grain mill or even McDonald's, to make some money for the barest essentials. He usually slept under the stars, or occasionally squatting. While the desert is completely opposite to Alaska, Chris logged more than two years demonstrating that he was more than capable of living outdoors, with few comforts or defenses.

Carine writes that she missed him during this time, but that, as time went by - their parents vacillating between worry and outrage - she understood innately that her brother needed to break from the family: to live by his own morals and provide his own sense of freedom. Maybe not forever, Carine hoped - but yes, for now.

He'd never have left her alone, at the mercy of violent, alcoholic rage-addicts Walt and Billie, she felt sure, unless he absolutely had to. So, she concluded, he must have really had to.

Still, she explains, as she grew up, finishing school and embarking upon relationships, some serious, she assumed Chris would be back to walk her down the aisle. As she developed business ventures, she believed he'd be there to grant his pride and approval.

But by now, we know that never happened. Chris died at his business campsite on the Stampede Trail in the Alaska Range, near Healy, in August of 1992.

**********************************************************Athis point, we turn again to the popular assumptions about Chris, most of which were both negative and developed before all of the facts were in. Together, Carine McCandless and Jon Krakauer have worked diligently to make sure the truth, so revered by their subject, is on the record about Chris himself.

33 years after his death, most of the lingering interest in the case is a debate over whether Chris was a clueless tenderfoot or an outdoorsman living by a philosophy worthy of respect. To paraphrase Krakauer in the introduction to “Into the Wild," I won't tell you what I think, but you'll soon know.

First, it's undisputed that Chris McCandless failed to take the expected precautions before charging into the Last Frontier. The biggie was that Chris did have a map with him, but not a topographical map, which is considered basic kit by outdoor adventurers all over the world. Why did this matter? It would have shown that he could save himself in a few ways.

Chris got stuck, hemmed in by a river - the Teklanika - that was easy to cross in May, but swollen to overflowing rapids in August as snow melt came cascading down from the mountains. He could have easily learned (or reasoned) that that would happen, but the topographical map, in particular, would have shown him that just a mile downriver lay a kind of zip line: a steel cable with a basket attached, used by Forest Service and park workers to cross to the other side when the river was rough. He'd have crossed with no trouble, able to simply walk out.

That topographical map would have shown him that there were as many as six cabins nearby within a three-hour walk of his camp at the bus. Most of those cabins were for park rangers, meaning they'd have been stocked with food, fuel, and medical supplies. This could have been a life-saving backup option, and Chris’ failure to arm himself with such a map is shocking.

But interested parties have failed, themselves: failed to ask themselves why Chris went about things this way.

Surely that helped to keep him alive in untold ways. But as for his lack of gear?

Chris McCandless wanted the experience to be about struggle. He had the arrogance and overconfidence of youth, to be sure - and this was the part of his story that engendered so much decision, especially from Alaskans, who only thrive in the harsh conditions through careful preparations. And Chris simply didn't do much in the way of preparation - hence the earlier anecdote about the boots. But what is continually overlooked is that he didn't want his experience to be comfortable. And I daresay he didn't want to thrive: He wanted to survive.

We may well say this was foolish, but we were not asked to die for Chris McCandless' ideals. Since he did not endanger anyone else or require an expensive extraction effort, his life - and death - were his business.

Next, there is the idea that Chris actually wanted to die. Because it would have been so easy for Chris to explore the area and find either the zip line or the cabins, even without the topographical map, many critics said that Chris must have been suicidal from the get-go. That, taken with a fateful postcard sent to a friend he’d made in South Dakota which said, “If this adventure proves fatal and you don't ever hear from me again I want you to know you're a great man," suggested to some that Chris intentionally created a set of conditions he wouldn't survive.

But Jon Krakauer Carine McCandless shows us otherwise. After a lengthy ordeal, she was able to take custody of the backpack Chris had used, which had been quietly taken away by a local. Upon its return to her, she looked among Chris’ Jack London novels, his Thoreau, and his Louis L’Amour, and she found his wallet. Inside were three still-crisp hundred-dollar bills: evidence that her brother, who eschewed personal wealth, meant to walk back out of the Stampede Trail and make his way back into society. (The money was donated in Chris’ name to the support of Alaskan wildlife.)

She also points to passages of Tolstoy she discovered amongst his belongings, underlined and dated in late summer, expressing that happiness is only real when shared. Alone in the Alaskan wilderness, the obvious assumption is that he meant to come back.

For his part, Krakauer adds, crucially, that all of Chris’ efforts were aimed at keeping himself alive - which he succeeded at for several months. His book includes the important observation that most of his critics had not, themselves, attempted to live off the land for an extended period. Importantly, Krakauer also notes the great physical conditioning Chris constantly subjected himself to, including both running and calisthenics to improve his strength, which surely saved his life untold times.

Finally, a third point of contention is food-related.

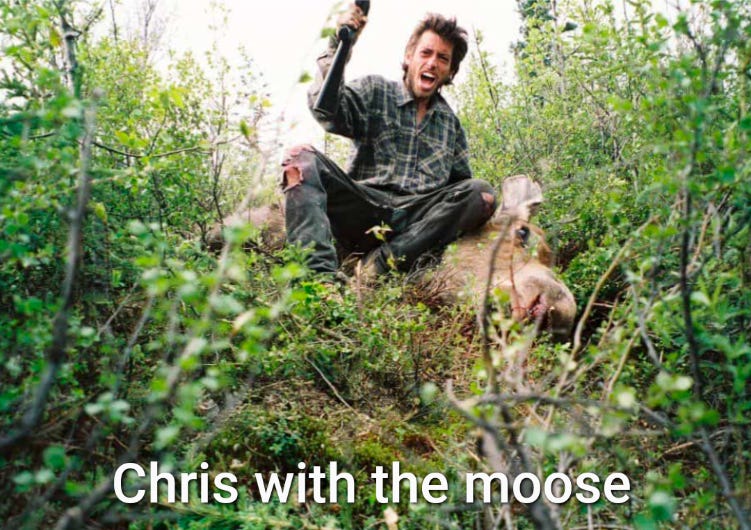

Chris recorded bagging a moose over his Alaskan summer. He tried to preserve it, so that it could feed him long-term, but was unable to, and he called the needless death “one of the greatest tragedies of my life."

When Chris’ remains were discovered, hikers assessed that the animal, whose carcass was still nearby, was actually a caribou. Lots of derision followed that assertion: "Anyone who can't tell the difference between a moose and a caribou has no business in Alaska!” asserted one ruthlessly unsympathetic letter to Outside magazine.

But a later inspection proved, through Chris’ own photos of the recent kill and a more careful examination of the carcass by more qualified judges, demonstrated that it sure was a moose. Chris certainly knew the difference between the two ungulates.

Then there was uncertainty around whether Chris really starved to death or became fatally ill from something else. Not an experienced hunter, Chris nevertheless managed to feed himself from the wild game that was abundant in the summer. That slowed down in late fall, but Chris did have a guidebook for the identification of edible local plants, which he'd purchased at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. He had eaten safe native plants to supplement his diet of protein and carbohydrates from the rice he'd brought along.

In the log he kept, Chris noted on July 30th that he'd become ill. The sickness appeared seemingly overnight, and it not only persisted, it got worse. Chris’ log shows a distressing entry shortly before his August death:

"Extremely weak. Fault of pot. seeds. Much trouble just to stand up. Starving. Great jeopardy."

As Chris’ story gathered steam, that line, “Fault of pot. [potato] seed,” took a back seat to his other entries, which referred to his weakness and the difficulty of finding game to supply him with meat. The extremely low weight of his remains seemed the last piece of proof that Chris just ran out of food and starved.

Once some of the sensationalism passed, though, much was made of the fact that the wild potato, or Hedysarum alpinum, a safe source of food used by area natives for hundreds of years, looks very similar to the sweet pea plant, or Hedysarum mackenzii, which also grows nearby. Looking back at the weakness Chris describes and the very clear statement that his condition was the potato seed’s fault, it seemed obvious to many that this overconfident young gun, who had hardly prepared for this at all, had simply mistaken the sweet pea for the wild potato and poisoned himself.

The implication was clear: that his death was his own stupid fault.

Indeed, that was the cause of death Krakauer himself went with in his original article for Outside magazine, “Death of an Innocent." But something didn't sit right.

Krakauer points out that the guidebook Chris was using, "Tanaina Plantlore: Dena'ina K'et'una," by Priscilla Russell Kari, had served Chris well the entire time, up until the end. He'd been using it correctly all summer. And he'd recorded many instances of eating the root of the wild potato plant with no ill effects - which is to say, without confusing wild potato for sweet pea. So what happened this time?

I cannot fully follow, as a scientist would, the twists and turns that Jon Krakauer valiantly pursued in a years-long quest to prove that something else had killed Chris: something that wasn't his fault. Krakauer collaborated with several different scientists at several different research facilities. Many hypotheses were proven incorrect, but each one led to a new insight or a new contact with a fresh perspective. Finally, the truth came out in a paper Krakauer coauthored in 2014 for the peer-reviewed journal Wilderness and Environmental Medicine - 22 years after the original article for Outside.

The upshot was that, while wild potato root is, indeed a safe plant to eat, as demonstrated in Kari’s book, the seeds of the H. alpinum plant contain a toxic amino acid known as L-canavanine. This fact wasn't in the guidebook at all.

And since few people had resorted to eating the plant’s seeds, let alone living to tell the tale in print, Chris could not have known. Indeed, L-canavanine poisoning primarily affected livestock, but most cases were not understood or tracked. It sounds safe to say that, broadly speaking, it wasn't just Chris who didn't know: Science itself did not know.

L-canavanine, Krakauer, et al. found, inhibits the body's ability to absorb nutrients from food. No matter how much the person eats after ingesting wild potato plant seeds, the body will never absorb it; will never nourish itself from that food. The end result? Yes: starvation.

And that's what was originally assumed. But Chris did not starve for lack of food, as was previously believed. Chris did not starve because he was a greenhorn; he did not starve because he made a stupid mistake. Chris starved because he happened to be the first person to document a fatal illness that was absolutely the “fault of pot. seed," just as his log book said.

Had Chris not eaten that particular part of the plant, when its root had gotten soggy and inedible with the change of seasons, he'd have kept himself alive until the river froze, and he'd have walked back out as jubilantly as he walked in.

Indeed, after his years on the road, Chris might have walked out in a much healthier space mentally and emotionally - perhaps enough to take a stab at reconciling with his parents, or at least to rejoin his beloved sister, Carine.

Chris McCandless sought after nothing as much as he pursued truth. If he could not find it in a California or Virginia subdivision, could not find it in his parents, could not find it at college or in the prospect of a career, I am glad that he found most of that truth he was seeking in the wild. From the California desert to the tiny town in South Dakota to the wilds of Alaska, he pursued it, and yes, I believe he died for it. Few are willing to do the same for their own ideals.

And I'm glad we got the record straight on the stupid potato seed. The least we can do for this scrupulous student of authenticity is to bring that same determination and commitment to the question of how he died.

He was running from abuse. And he died at peace, having gone joyfully into the wild truth.

Beautiful article!

Beautiful writing. Thank you.