Sally's Second, Very Personal Reason for Fighting Antisemitism: Part II

The lessons of my Quaker heritage are a guiding Light.

Earlier this week, I discussed the ways in which my German heritage, and my experiences living in Germany myself, inform my understanding of the Holocaust. In turn, that understanding fuels my desire to intercept and speak out against growing antisemitism.

Sigh. It's all fun and games until someone mentions Hitler, right? Today, I want to explain the other personal factor in my motivation. It's another family legacy, but it's a much more positive one.

Although my heritage is mostly German, through my grandmother, I am English and Quaker. In fact, that strain of the family has been Quaker - or, more formally, members of the Religious Society of Friends - going back hundreds of years, to the infancy of the movement. I grew up a practicing Quaker, and although I had nothing to do with my ancestors or the values they happened to hold, I'm proud, anyway, to be part of the passing down of this uncommon religious and cultural tradition.

And it really is uncommon! We Quakers are a pretty small group. One of our organizing bodies, the Friends General Conference, estimates the North American population of the group at about 81,000. To put that in perspective, that means that, relative to the whole population of the United States and Canada, the proportion of Quakers is represented roughly by the city of Flint, Michigan.

If your brain read the word “Quaker” and said, “Ah, yes; that is something I've heard of before,” chances are that it's because you've eaten the oatmeal. Or maybe you've used the motor oil. Fun fact - as you can see in this Wikipedia entry, it was once fairly common for businesses to attach or invoke the name of image of Quakers as they marketed their products. They hoped to capitalize on adherents' image as reliably honest and moral.

Though our name sounds hopelessly old-fashioned, Quakerism is much more modern than many people realize. For one thing, we are not Amish (hey, sometimes there’s confusion): Unlike the guy on the box of oatmeal, modern-day Quakers no longer dress as if we’ve escaped from a politically-incorrect Thanksgiving pageant. Early Friends aimed to wear only dark, muted colors, as a way of rejecting personal vanity and keeping their minds on loftier matters. I'm glad we threw that idea out the window - give me neon or give me nothing!

We’ve also stopped using “plain speech,” or calling everyone “thee.” That was done in service of rejecting honorific forms of address and, instead, putting into action our belief that all of God’s children are inherently equal. And nowadays, most Quaker Meetings, or congregations, do include music in Sunday services, which was once forbidden as another distracting frivolity.

But we do still have some of that lingering reputation for being honorable people who work to do good. Interestingly, that legacy is linked with how very modern our group once was. In fact, that olden-timey-looking guy on the box of oatmeal was a real radical. For one thing, he and his brethren believed - as we still do today - that no priest, pastor, or other intermediary is necessary to communicate with God. Rather, Quakerism teaches that God speaks directly to every person. That was a real wrench in Big Christianity's gears! It also happens that Quakers were among the first Americans to realize that something was very, very wrong with the concept of slavery.

During the 1800s, my Quaker ancestors, Elizabeth Newman Edwards and her husband, William, ran a prosperous farm in the mostly-Quaker community of Raysville, Indiana. With their children, they lived and worked there in the lead-up to, during, and after the Civil War. As you may know, the dividing line between the Union and the Confederacy was the border between Indiana and Kentucky. So, while Indiana, to the North, was not a slave-holding state, that didn't mean that it wasn't a hotbed of political action at the time of the Civil War. Many prominent - and very impactful - abolitionists and Underground Railroad champions were based here, and Quakers were at the forefront.

Opposing slavery was not always a consensus among American Quakers, but early abolition activity was recorded by 1715. By 1775, the mostly-Quaker Pennsylvania Abolition Society had taken shape and was working in an activist capacity. And the Quaker abolitionist poet John Greenleaf Whittier brought considerable attention to the movement in poems like “At Port Royal 1862,” which describes the arrival in Port Royal, SC, of Northern abolitionists. These were sympathetic allies who had come South to help to teach and steward the many enslaved people abandoned at plantations when their owners left to join the war effort.

Similarly, many Indiana Friends felt so strongly about the need for chattel slavery to fall that they contravened their Meetings' pacifist teachings to join the Union Army and fight for their beliefs. Quakers do not believe in violence or war. Some of us concede that certain wars need to be fought, but most Quakers experiencing a draft into the military would have been expected by their faith communities to conscientiously object. That meant that, during the Civil War, many young Quaker men who followed their “leadings” and chose to fight for their principles ended up “written out of Meeting:” kicked out of their church communities. Sometimes they were able to return, but the rebuke would've been akin to being shunned.

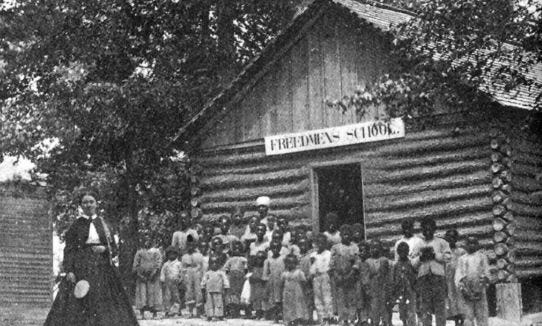

However, once the North had its victory and slavery became illegal, there was another way for passionate, able-bodied Quakers to support the influx into society of formerly-enslaved people, or Freedmen. And it was not looked down on at all, but rather, greatly encouraged by Quaker congregations. A network of Yearly Meetings, or localized Quaker overseeing bodies, worked with the newly-created Freedmen's Bureau to scout their Meetings for Friends with teaching experience who were willing to travel South to help to educate the Freedmen. After all, in the aftermath of the Civil War, there was suddenly a sizable population of people who needed to support themselves - and wanted to contribute to society - but often lacked the ability to read or write. Many had never experienced any education at all, and were starved for it.

But, predictably, most of the Freedmen's Southern neighbors, who could have helped, were not interested in providing these newly-freed citizens with education. For that reason, intervention and assistance were sought, and found, in the North. Quakers, who had been advocating for abolition for more than a century, seemed likely to be natural allies. And they were: Quaker congregations sent hundreds of teachers, many very young, below the Mason-Dixon line to work as teachers for the Freedmen.

These very brave teachers were paid relatively little - and that unreliably - to undertake arduous journeys to teach in unknown circumstances in literal enemy territory, where they were not welcome. Southerners knew that Friends opposed the financial engine that powered nearly the entire South, and on top of that, they wanted to treat this group of people, who had only recently been considered white people's property, as if they had rights. To many, that was galling. But the real problem was that these Northern Quakers were coming South, into their cities, their towns, where they didn't belong and didn't understand the culture, to try to tell them, the Southerners, what was morally right and wrong. As one might expect, many Southerners took umbrage at this.

In this way, the Quaker teachers' work was made downright dangerous. Due to their distinctive manner of speech and dress, members of the Religious Society of Friends were easy to spot - especially women, whose elaborate attire would've provided so many more ways to pointedly stand apart from secular fashion. As a result of the ill will toward them, the young teachers faced regular violence and harassment. In some cases, teachers had been deliberately misled about this risk, and would only learn how unwelcome they really were in Southern cities when they showed up for their new jobs teaching Freedmen, and found shopkeepers and farmers unwilling to sell food to them. Similarly, they had a difficult time finding accomodations to rent or people to work with them.

These would be unnerving and difficult working conditions even now, but some 150 years ago, the Quaker Freedmen's Bureau teachers had far fewer protections and resources than we do today (and we still have a long way to go). Still, these young teachers believed they were doing the Lord's work, putting in their own elbow grease to realize their convictions that all people were equal, and should be treated as such. So they simply did the job anyway.

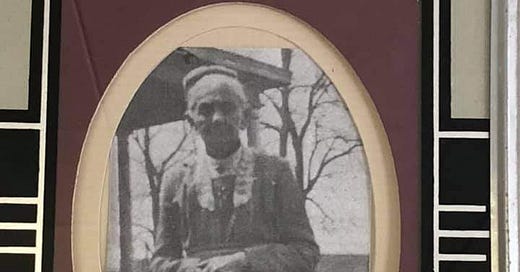

But wait. How do I know this? Where are all my orange links? Well! I know all of this because two of those young women - those determined and faithful Northern Quaker educators, who traveled to the Deep South during Reconstruction, in order to teach in the new Freedmen's schools - were my fourth great-aunt and my third great-grandmother, Mary Jane and Lizzie Edwards. And, incidentally, my fourth great-uncles, their brothers, were written out of Meeting for defending their religious beliefs by joining the Union Army.

These two young women, Mary Jane and Lizzie, were filled with the Light of God, the desire to be of service, and, we have to assume, some serious spunk. So they left their family farm in Raysville, Indiana, and traveled as far South as Jackson, Mississippi, to teach classrooms full of dozens of people who wouldn't even be able to read the lessons they wrote.

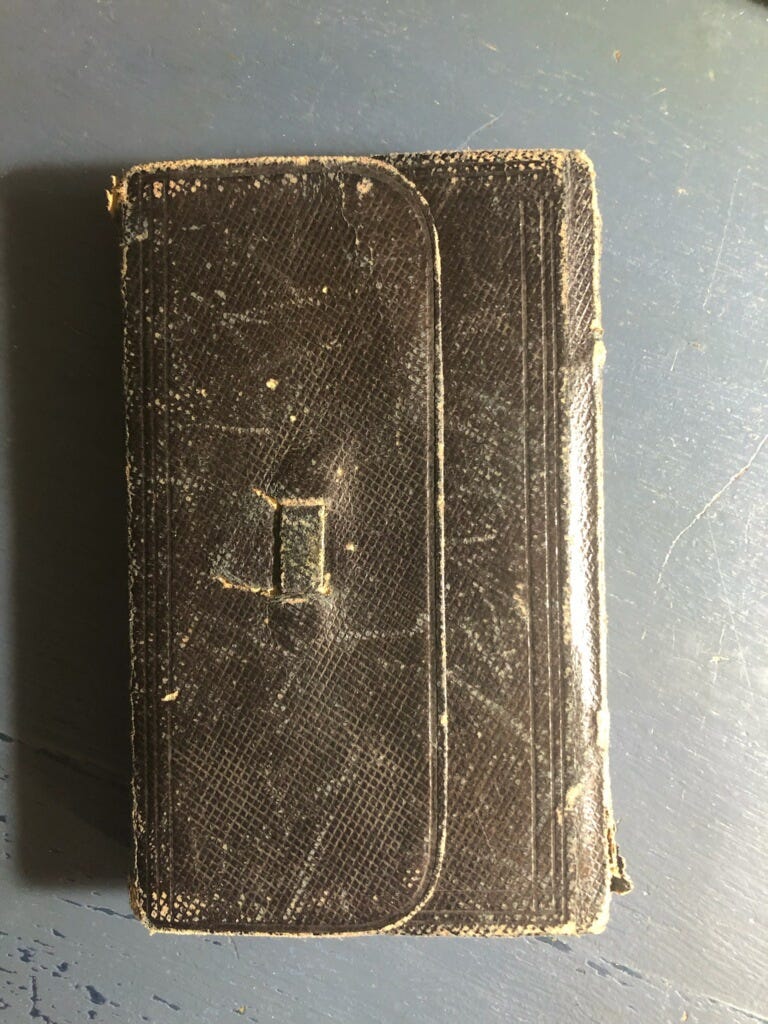

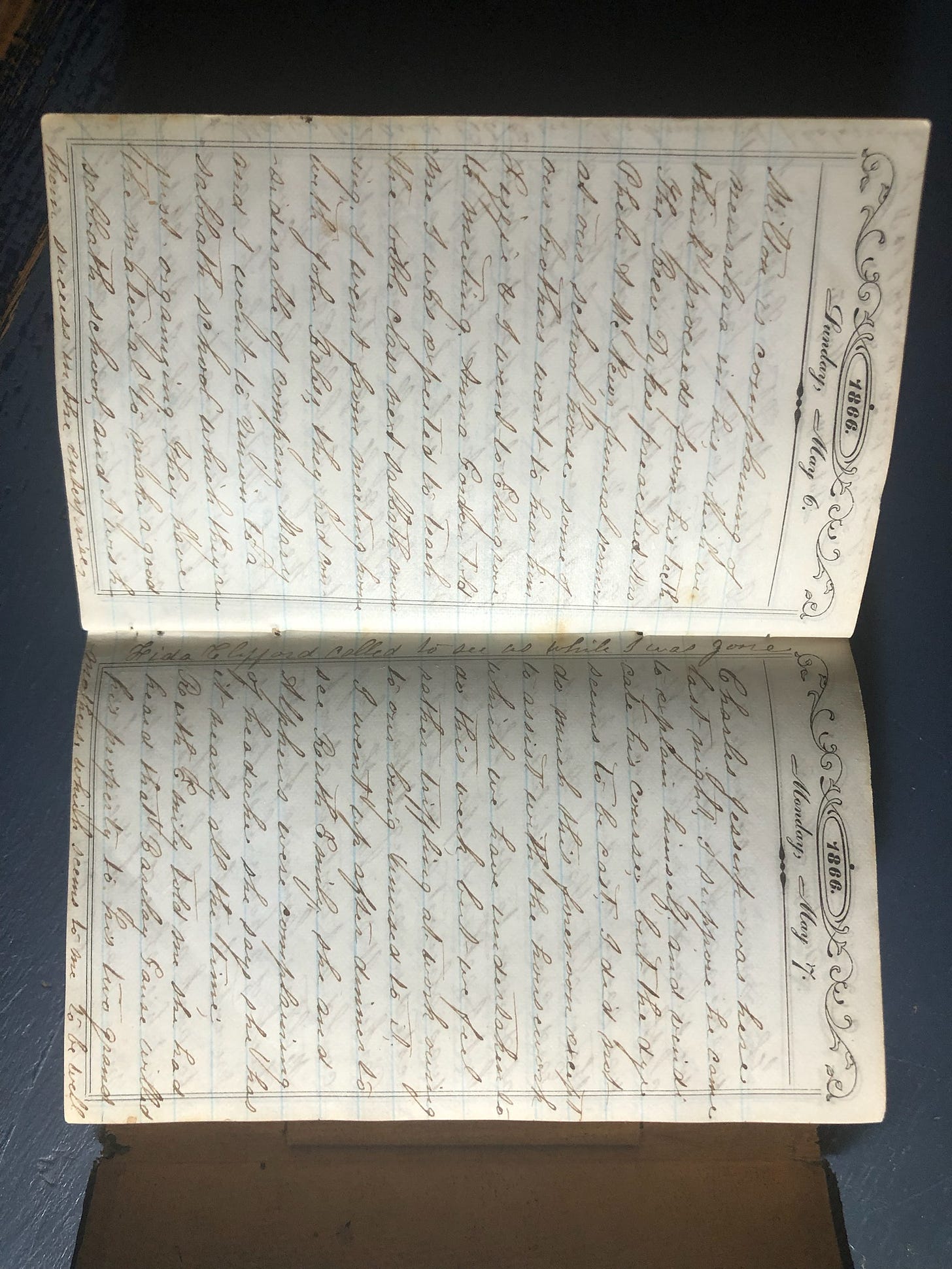

You know what's cool? Mary Jane kept a diary of her experiences in the South as a teacher of Freedmen.

You know what's really cool? My family still has it. We have the actual diary. It's 157 years old.

Four generations of my family - my great-grandmother, Rosemary, my grandmother, Marilyn, my mother, Barb and her sister, Jan, and my own brother, Ted - have worked for decades to bring this piece of history to life. They have spent eye-watering hours parsing that faded brown ink on thin pages, transcribing the diary into type we can read easily. A crack researcher, my brother, especially, has spent years now combing census records, plat maps, church documents of the time, and other records I don't even know the names of, looking up the people and places mentioned in its pages to verify, locate, and cross-reference information. And my mother won a Lilly grant for her and my aunt to spend a hot, frustrating, exhilarating summer following in the sisters' footsteps, from Raysville, Indiana, to Jackson, Mississippi, and points in between, to learn firsthand about their journey, their work, and the remarkable roles they played in this period of history.

I could tell you so much about Mary Jane and Lizzie. I could tell you so much about all of the remarkable Quaker women of my family! And I will - over time. But it's delicate. Our family has grappled with who, exactly, this legacy “belongs” to, if anyone, and who “gets” to tell the Edwards sisters’ story. We want to present Mary Jane and Lizzie as they likely were - brave women, professional teachers, who were asked to use their skills to benefit a group of people their church had long been advocating for. They agreed, and that's remarkable. But we don't want to lionize them, or to suggest that they were saints. They were human, and were both very much products of their time.

I was not as involved as I'd hoped to be in the transcription and research of the diary, although it interested me greatly. I was dealing - or, rather, not dealing - with the end of my first marriage to a man from the still-tight-knit Indiana Quaker community, and somehow, the deep dive into our shared heritage made me uncomfortable. I also have a physical handicap that limited my ability to tromp through very old, disused cemeteries and the like, as was necessary on multiple occasions.

But I followed the investigation avidly, and I came to believe that the sisters' story is at once theirs, everyone's, and no one's. It's there for anyone who's interested in it. And think I know what my unique contribution to its telling can be. I can follow in the sisters' footsteps by standing up for the equal treatment and acceptance of all minorities. I can talk about how important it is to learn from what past instances of sanctioned, institutionalized hate have yielded. I can be an ally today.

We Quakers are supposed to be pacifists, and I certainly prefer to approach conflict peacefully. My partner favors bombastic, in-your-face rhetoric that inspires strong opinions and incites decisive action. That's probably why I won't end up converting him, and that's okay! But some conflicts are carried out in service of greater peace in the future, and that's why I stand with Dave in his passion of making antisemitism absolutely unacceptable.

Very interesting, Sally! This has given me a much broader understanding of your mother's summer trip of investigation with the Lilly grant. I look forward to the updates to come to learn who will ultimately take possession of the story.

Loved reading about this bright candle of light in American history and your family's part in it. Thank you for sharing. — Glenn Perlman