Pearl Harbor in Memory, Myth and Movies

The great shift that the place Pearl Harbor harbors in our popular culture occurred in Hollywood and it still impacts how we think about this catastrophe today.

It is hard argue there was ever a disaster in American military history on the scale of Pearl Harbor. Maybe the battle of Long Island (1776). If the rebel army had been destroyed and its commander George Washington killed or captured, today we might all be speaking English.

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor could have sealed American defeat in World War II. As it was, it was a near run thing. Even though America ultimately didn’t lose the war, the defeat did allow Japan to run amok in the Pacific theater for almost two years. Crippling the American Pacific fleet, put the US Navy on its heels, a precondition for the campaign that carried Japan from the Malay Peninsula to the Philippines, Wake Island in the Western Pacific, southwest to Rabaul and shores of Papua New Guinea. The decision to sink the American ships docked at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii became one of those world-changing moments that truly deserves that label.

A battle that consequential, on the scale of Waterloo (1815) or the Battle of Zama (202 BC), could not help but become a crucial part of our national memory, myth, and movies.

The squabbling over the legacy of Pearl Harbor began almost as soon as the last bombs fell. Just like 9/11 and J6, Congress almost immediately began an investigation, creating a Joint Committee on the Investigation of the Pearl Harbor Attack, commonly known as the Pearl Harbor Committee.

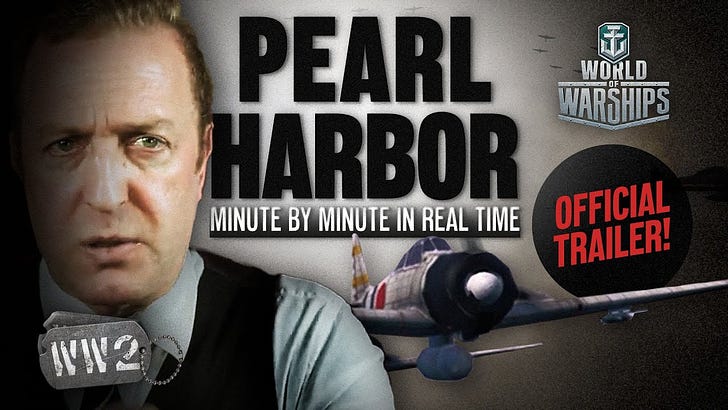

The most famous book on the topic was Gordon Prang’s At Dawn We Slept: the Untold Story of Pearl Harbor. Notable as well was Pearl Harbor: Warning and Decision by Roberta Wohlstetter which attempt to derive insights from the disaster to avoid a surprise Soviet nuclear attack. Right now on Netflix there is a documentary Attack on Pearl Harbor: Minute by Minute (2021).

Still, not surprising, the great shift that the place Pearl Harbor harbors in our popular culture occurred in Hollywood and it still impacts how we think about this catastrophe today.

In 1966, more than a quarter century after the lightning strike that killed 2,403 Americans and sunk or damaged 19 ships, including eight battleships, Hollywood producer Daryl Zanuck decided it was time to make a big movie about this fateful day. The war was still a vivid part of America’s modern memory. Dwight Eisenhower who led the great crusade to liberate Europe was only five years out of office. Winston Churchill had died only a few months before Zanuck conceived his grand project. Further, the burden of the Vietnam War had not yet soured the nation on celebrating Americans warring overseas. It was the perfect time to find a big audience for a big movie.

Zanuck had every reason to hope that he could deliver both an iconic film and a box office bonanza. He had done it before. In 1962, Zanuck produced The Longest Day an epic tableau of the Normandy invasion. His plan was to copy that formula. And, he added a wrinkle that he thought would make the film a sure fire classic. The Japanese side of the story would be fashioned by the acclaimed director Akira Kurosawa. American audiences knew the filmmaker mostly through his well-regarded samurai films like Seven Samurai (1954) and Yojimbo (1961). Kurosawa screamed the perfect combination of prestige and popularity—a ticket seller’s dream.

Japan’s most famous director was thrilled with the project. He longed to bring a sentiment to the story that would bridge the historical war legacies of his homeland and the United States—now fast and firm postwar allies. “This movie will be a record of neither victory nor defeat but of misunderstanding and miscalculations and the waste of excellent capacity and energy,” he declared at a news conference announcing production of the film, “[a]s such, it will embrace the typical elements of tragedy. I want to look straight into what it means to be a human being in time of war.” His ambitions transcended Hollywood. He would make a film that would move nations and touch their soul.

That was the plan.

Japan’s “master of cinema,” never saw his grand vision reach a theater.

After many months of frustration, cost overruns, and stupefaction over Kurosawa’s erratic behavior the studio dropped him from the project. Eventually, there was a film—Tora! Tora! Tora! (1970), the title drawn from the code word (translated as tiger, tiger, tiger) sent by the leader of the first wave of Japanese fighters reporting that they had caught the American defenses at Pearl Harbor by complete surprise. The movie looked only vaguely like Kurosawa’s magisterial, but sprawling and arguably unfilm-able screenplay that read more like War and Peace (the novel) than a script. The first draft (over 1,000 pages) would have delivered a seven-hour movie with 706 scenes.

The producers did manage to stay true to the original concept of telling both sides of the tale. Still, the film received glum reviews and got shutout at the Academy awards.

Though the movie has largely faded from modern movie memory, it remains the defining Pearl Harbor film (a much more important cinematic effort than Pearl Harbor, the schlocky 2001 romantic action flick which made way more money and received four Academy Award nominations).

Tora! Tora! Tora! tried to follow Kurosawa’s vision, viewing Pearl Harbor as a shared Shakespearean tragedy. Japanese audiences responded to the courage, determination, and professionalism of the Imperial Japanese Navy. Americans took solace in the film’s final scene. Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, the commander-in-chief of the Combined Fleet, looks out to sea across the deck of his flagship while his words scroll across the screen subtitled in English, “I fear all we have done is to awaken a sleeping giant and filled him with terrible resolve,” foreshadowing the terrible retribution for the Japanese attack.

In the end, Kurosawa was right. Audiences accepted the film’s premise—history had thrown the two nations into war.

Nevertheless, neither history nor the film, however, diminished the enormity of the military disaster and the unsettling shock to Americans who felt the broad oceans kept their homeland safe. No one walked out of the theater thinking anything less than that Pearl Harbor was one of the greatest American military disasters of all times.

Pearl Harbor, however, became dissociated from Japan in modern memory, reduced to a metaphor for unexpected disaster.

Like much as in contemporary popular culture, how contemporaries view Pearl Harbor tells us more about their politics than the history of Pearl Harbor.

Today, for example, experts on the left like Leon Panetta often talk about a cyber Pearl Harbor, as the next unexpected kick in the teeth, treating surprise enemy attacks like some kind of unanticipated road accident.

In contrast, conservatives, invoke another Pearl Harbor as a warning against the danger of unpreparedness, resulting from the failure to see rising threats and deter them before they smack America in the face.

All that goes without saying, today when someone says “No More Pearl Harbors,” don’t assume everyone knows what they mean by that, other than that we’re not expecting another attack from Tokyo.