'Old Truths and New Cliches': Rare, Salvaged Gems from Isaac Bashevis Singer

Celebrating one of my very favorite writers

Isaac Bashevis Singer (1903–1991) was a prolific, Polish-Jewish-American, Nobel Prize–winning writer who stands very high in my personal pantheon; I rank his greatness just a notch below the level of Tolstoy and Dostoevsky. Born near Warsaw, Singer emigrated to New York City in 1935. Writing in his most intimately native language, Yiddish, it was in America that his works were translated—usually by Singer himself with a collaborator—into English, and they went on to attain worldwide fame.

Though known mainly for fictional works like the novels The Family Moskat and Enemies: A Love Story and short-story collections like Gimpel the Fool and The Spinoza of Market Street, Singer was also a very prolific journalist and essayist. At first, in America, he wrote journalism for the Yiddish press to make a living; later his essays were translated and much more widely published in periodicals. But, while Singer wanted to put out an essay collection during his lifetime, his publisher was more concerned to cultivate his image as an “old-fashioned storyteller,” not as some sort of egghead, and it didn’t happen. Here it’s worth noting that while Singer’s fiction is indeed written with wonderful narrative simplicity, its content is often quite modernist in highlighting despair and existential crisis.

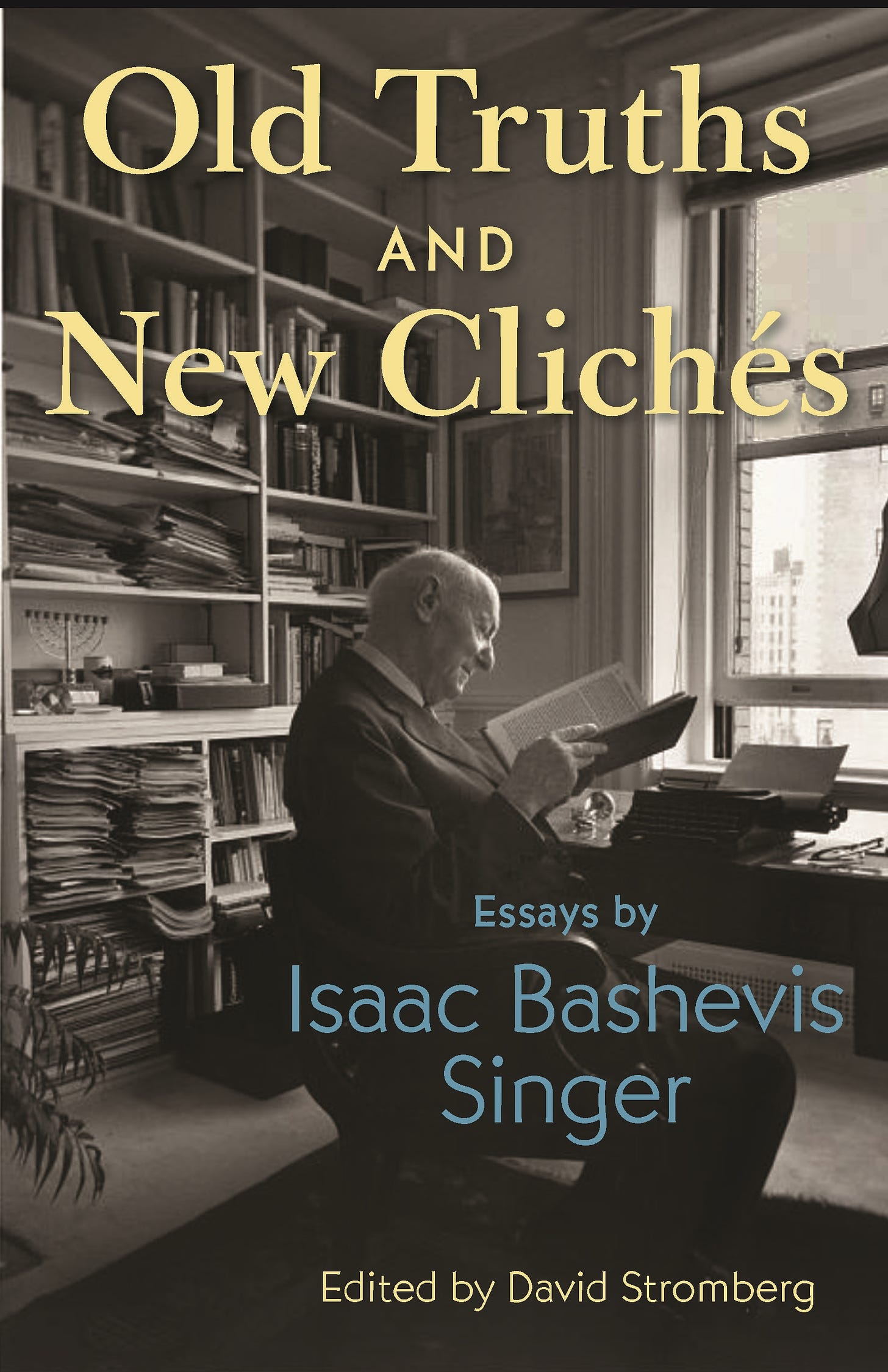

Old Truths and New Clichés, compiled painstakingly by writer and devoted Singer scholar David Stromberg, finally brings to light some of the essays Singer made sure to have translated into English and most hoped to see in a collection during his lifetime. These salvaged gems share with his fiction the superb Singerian brew of directness, vividness, richness, and profundity.

Divided into three sections, the book’s first section offers Singer’s thoughts on writing and writers, and indeed one of its most sparkling essays challenges the notion that journalism is just a foil for fiction. Having practiced both of those myself, it was bracing for me to encounter Singer’s explicit insight that journalism and fiction are in fact not adversaries of each other but complementary. Yes, it’s true: both of them need to present something new and unique; both should focus primarily on facts, not interpretation; and both are obliged to be entertaining. Indeed, Singer felt that he wrote some of his best fiction while he was also writing journalism; I know what he means, though I never formulated that thought to myself.

The second section deals with Jewish issues that preoccupied Singer even more than all the others he grappled with. Raised in a Hasidic home, his father a rabbi, he developed doubts and misgivings about religion early on and eventually emerged as a young, secular Jewish writer. But Singer had doubts and misgivings about secularism, too, and his fiction is replete with the tension between religion and secularism, repeatedly featuring a main character who hovers disconsolately between the two worlds and can truly find a home in neither of them.

Ever wondered why Hasidic and other ultra-Orthodox Jews dress so strangely and keep themselves apart? Singer’s essay on this subject, “The Spirit of Judaism,” may be the best concise, deeply knowledgeable but detached, nonjudgmental explanation of the phenomenon anywhere. It stems, he elucidates, from Jews’ need to survive as a distinct people during two thousand years of dispersion, which required standing firm against intermarriage and assimilation. For strictly pious Jews in today’s world, it means keeping a distance not just from non-Jews but from other Jews as well. And it’s clear that Singer, in his complexity and open-mindedness, harbors admiration for that resilience despite having crossed over to the secular side himself.

Yes, secular and not formally religious; but Singer, apart from a brief interlude of atheism, remained—as is well evident in his essay on “The Kabbalah and Modern Times”—intensely theistic and preoccupied with the matter of God. Again, this piece is a concise and wonderfully informative overview of the Jewish mystical tradition—including the fascinating concept of tsimtsum, of God contracting, limiting himself, so that a world could be born that was inevitably imperfect because it was at varying degrees of distance from Him, but in which the human drama of striving to return to His light could be played out.

The third and last section, “Personal Writings and Philosophy,” sustains the wit, brilliance, and intensity. In two of the pieces, “Why I Write as I Do” and “A Personal Concept of Religion,” Singer develops his theme—among other topics, of course—of God as a creator and, indeed, a novelist, which is a perhaps eccentric but strikingly original and suggestive way of conceiving it.

Like…myself, God threw his unsuccessful works into the waste basket. The flood, the destruction of Sodom, the wanderings of the Jews in the desert, the wars of Joshua—these were all episodes in a divine novel full of suspense and adventure…. God is not static perfection as Spinoza thought, but a limitless and unsatiated will for perfection. All his worlds are nothing more than stages and experiments in a divine laboratory…. God, like the artist, never knows clearly what he will do and how his work will develop. Only the intention is clear: to bring out a masterpiece and to improve it all the time. I once called God a struggling artist. This continual aspiration is what people call suffering. In this system, emotions are not passive as in Spinoza’s philosophy. God himself is emotion. God thinks and feels. Compassion and beauty are two of his endless attributes.

It's rich stuff, hinting at…if not solutions, then different ways of looking at the theodicy—the riddle of how an allegedly good, omnipotent God could be compatible with so much evil and suffering.

Singer’s essays, like his fiction, rush along with his genius-energy while at the same time inviting, and rewarding, deep concentration. We’re indebted to David Stromberg for spending years hunting these down, reconciling different versions of them, and carefully shaping them into this invaluable collection.