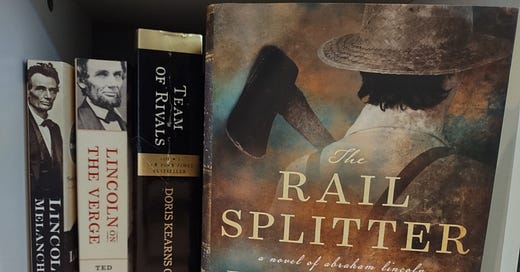

New Lincoln Novel Fills in the Gaps

Historical fiction can supplement nonfiction nicely. The Rail Splitter provides a great example.

The recently released novel The Rail Splitter by John Cribb follows much of Abraham Lincoln’s life, beginning with his youth in 1826 and taking us up to his decision to run for president. (The narrative continues in Cribb’s previous novel, Old Abe, which I have not read.)

When I read nonfiction biographies of historical figures like Lincoln, the early years tend to be the least interesting. Understandably, the historical detail simply doesn’t compare to that of later years, after they’ve entered the public sphere and begun their notable work. And this is where historical fiction can help us fill in the gaps.

In a brief author’s note at the beginning of the book, Cribb describes his efforts to paint an accurate picture of his subject. He says he used “hundreds of primary and secondary sources, drawing on the words of Lincoln and his contemporaries when possible.”

Artistic liberties were, of course, necessary to interpret Lincoln’s life as a novel.

“The line between history and legend is sometimes thin, and there is, no doubt, some lore mixed into any account of Lincoln. I’ve tried to be faithful to the spirit of his life and times,” Cribb writes.

As far as I can tell, he’s succeeded. For me, this novel reversed my usual interests in reading about historical figures. In this form, the early years were the most compelling.

The first chapter establishes young Lincoln’s character by detailing an anecdote about a book. Abraham had inadvertently let a book get water-damaged, which would have been bad enough if it was his own book. But the book belongs to someone else, and even at this young age, Abraham feels compelled to admit to his mistake and set things right as soon as possible. This puts him into conflict with his father, Tom Lincoln, who can’t understand why a young man needs more than the minimum education anyway.

The book, The Life of George Washington by David Ramsay, becomes a nice symbol of young Abraham’s potential in the early chapters, and it foreshadows how his life’s path will drastically diverge from his father’s.

While Cribb’s Abraham Lincoln demonstrates many admirable qualities throughout the book, he never comes across as a perfect saint. Some of his virtues are learned through error. For example, Lincoln writes some political letters to the Sangamo Journal in 1841. Behind the mask of anonymity—which proves to be a thin mask—he hurls insults at a Democrat named James Shields. The conflict leads to the brink of a duel, bringing him much embarrassment.

The novel delves into personal matters as well, such as Lincoln’s doubts about marrying Mary Todd, in which he went so far as to break off the engagement before ultimately reconciling.

The novel is at its weakest later when it recounts better-known historical events, particularly the debates against Senator Stephen Douglas in 1858. It’s not that Cribb does anything wrong. The scenes ring true and match the spirit of what I’ve read in nonfiction. I even recognized some of the quotes. But these parts of Lincoln’s life are best served in nonfiction, where they can receive a more thorough and purely factual account. In historical fiction, we have to take the details with a grain of salt.

The parts between, however, remain strong. The final chapter gets into Lincoln’s head as he wrestles with the decision of whether or not to run for president. Obviously, factual nonfiction can’t take such liberties, but in this novel, Cribb pulls it off in a plausible way that feels consistent with the Lincoln we know.

By bringing to life these in-between moments, Cribb humanizes Lincoln, presenting him as a fallible but capable individual who never takes his success for granted. The Rail Splitter gives Lincoln room to breathe and helps us better understand the man behind the historical events.