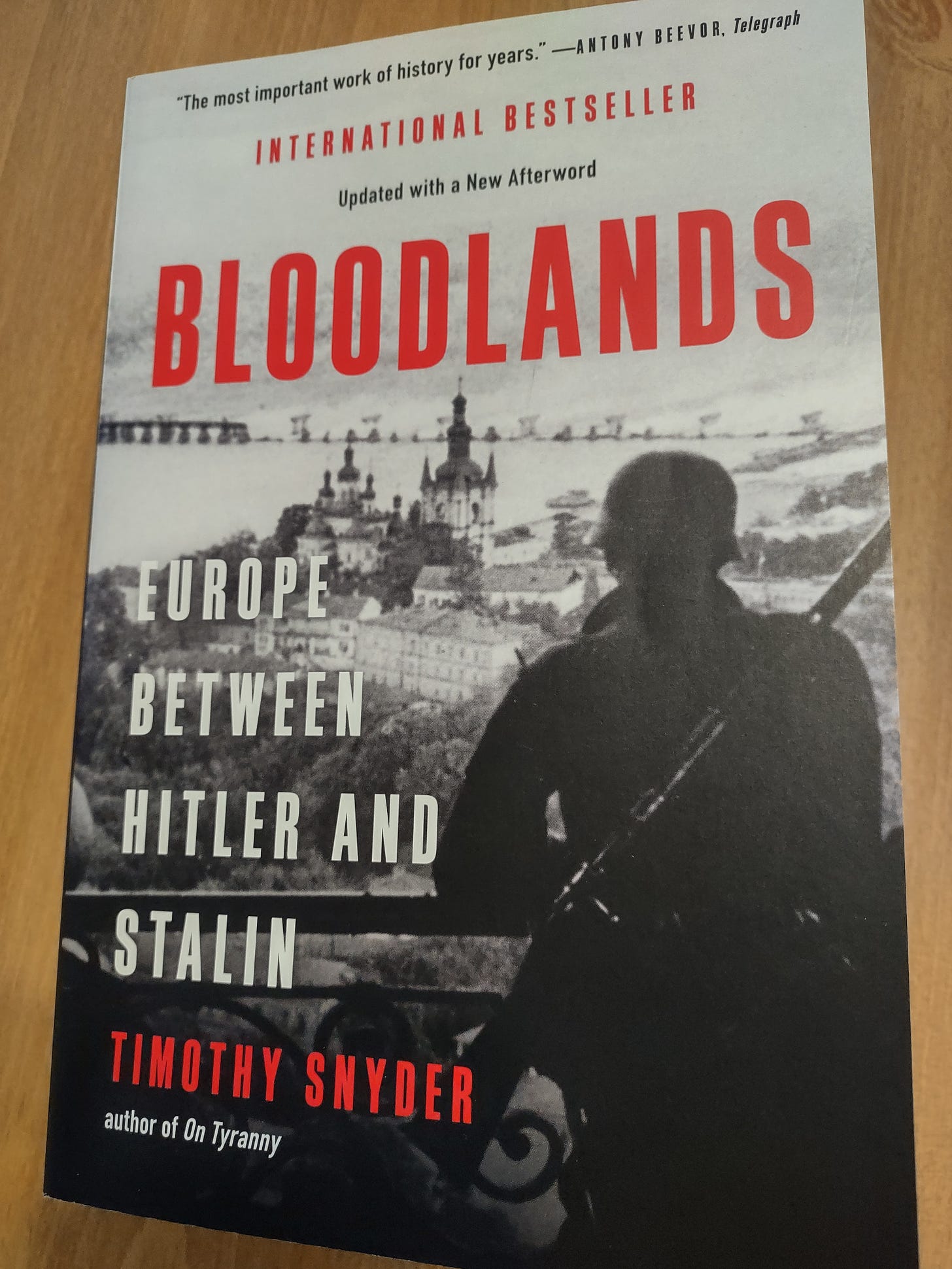

If you want to read about pure evil, check out Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin by Timothy Snyder.

Through no fault of Snyder’s, this is a hard book to get through. Most of us (myself included) prefer not to think about real-world atrocities in which millions of people died. But these atrocities happened, and we need to remember them. The book’s conclusion, appropriately titled “Humanity,” spells out why.

The conclusion is nearly 30 pages in the paperback edition and warrants some reflection. The first paragraph begins, “Each of the living bore a name.” The second, “Each of the dead became a number.”

According to Snyder, politically directed famine killed more than 3 million people in Soviet Ukraine; Stalin’s Great Terror killed about 700,000 people; Soviets and Nazis killed about 200,000 people as they targeted Poland from 1939 to 1941; Nazis killed about 4 million Soviet prisoners of war and Leningrad residents; Nazis killed 5.4 million Jews in the Soviet Union, Poland, and the Baltic States; and the Nazis killed half a million civilians in wars for Belarus and Warsaw.

These atrocities occurred between 1933 and 1945 in the region Snyder categorizes as the bloodlands.

Toward the end, Snyder focuses on more specific numbers and, more importantly, the lives those numbers represent: “Each record of death suggests, but cannot supply, a unique life. We must be able not only to reckon the number of deaths but to reckon with each victim as an individual.”

He advises us to view the Holocaust’s 5.7 million Jewish deaths not just as a large abstract number “but as 5.7 million times one” (italics in the original).

“This does not mean some generic image of a Jew passing through some abstract notion of death 5.7 million times. It means countless individuals who nevertheless have to be counted, in the middle of life,” Snyder writes.

He suggests that we’ll be better able to “turn the numbers back into people” when we don’t round off those huge numbers and when we look at the one’s place and consider who those few lives may have been.

Snyder says that “it might be easier to imagine the one person at the end of the 33,761 Jews shot at Babi Yar: Dina Pronicheva’s mother, let us say, although in fact every single Jew killed there could be that one, must be that one, is that one.”

And he’s exactly right.

A short passage from much earlier in the book also stuck with me. Snyder observes how Hitler and Stalin effectively provided cover for each other:

“By presenting the Soviet Union as the homeland of ‘anti-fascism,’ Stalin was seeking after a monopoly of the good. Surely reasonable people would want to be on the side of the anti-fascists, rather than that of the fascists? Anyone who was against the Soviet Union, was the suggestion, was probably a fascist or at least a sympathizer. …

“European public opinion was so polarized by 1936 that it was indeed difficult to criticize the Soviet regime without seeming to endorse fascism and Hitler. This, of course, was the shared binary logic of National Socialism and the Popular Front: Hitler called his enemies ‘Marxists,’ and Stalin called his ‘fascists.’ They agreed that there was no middle ground.”

The overzealous activists and ideologues of today should take that as a warning. Even though history doesn’t repeat precisely, it can rhyme, as someone said.