Maybe This Time / I'll Be Lucky 🎵

On Laurel Canyon dreams, turning 40, and singing my heart out

When I was in my late teens and early 20s, I wanted to be a folk singer. Remember this if we're ever on a game show together and they separate us and ask us questions about each other: When I was in my late teens and early 20s, I wanted to be a folk singer.

Back in the heady early-to-mid 2000s, this was admittedly a strange aspiration. Folk rock had enjoyed a moment there in the late 90s, and I admired singers like Lisa Loeb, Shawn Colvin, Sarah McLachlan, Natalie Merchant, and Sheryl Crow. I'd even learned and perfected their songs, but it wasn't very popular music anymore.

Never mind that, I decided! As a former theatre and band kid, I’d been told I had a decent mezzo-soprano singing voice. Well, OK: I'd been told I was good. I also had the ability to reproduce a song on the piano after hearing it just a couple of times, in order to accompany myself.

So this folk-singing goal was a natural place for me to end up, a mix of both my talents and my modesty. This, I would learn later in life, was mostly an affectation I put on for the sake of etiquette and decorous comportment, with the result that my personal message to the world became a contradictory mix of “I'm actually pretty talented” and “Seeking attention is beneath me.”

I was the kind of kid who, for personal reasons, needed always to be perfect. Bafflingly now, I believed I'd hit the mark by having cultivated several gifts and aptitudes that I could trot out if invited, but only if. I was mortified when my Senior Superlative for the yearbook was listed as “Most Talented." Did they think I was a show-off? I fretted. Showing off was definitely not perfect.

But I did not entirely understand myself to be a character in a Jane Austen novel. I was also the kind of kid who made her own bell-bottoms in high school. With my mom’s instruction, I fashioned them by cutting up the outer side seam of my jeans and sewing in a fabric triangle to make them flare out. So folk singing was just my speed: much better than haunting karaoke bars or trying out for a new show called “American Idol” - which, where I lived at the time, bore the rather clunkier name of “Deutschland Sucht den Superstar.”

Finally, in a late-teenage fit of individuation, my desire to use some of those endless lessons and practice sessions while cosplaying as a flower child bubbled over. It had to! And so, while living abroad, I began to go into coffee shops and bars to play piano and sing a mix of classic and recent folk songs. Peter, Paul, and Mary were in heavy rotation, as were the Mamas and the Papas, the Byrds, Janis and Joni, and tunes the more contemporary singers above had released.

I was rather like Phoebe on “Friends," except with a piano instead of a guitar - and a distinct and unapologetic lack of songs having anything to do with smelly cats.

And people liked it - on two different continents, no less! Or if they didn't, they expended far more enthusiasm on faking it than made sense. But even half a lifetime ago, I was convinced that nothing could possibly be worse than becoming famous or even well-known. And I still am! I'm not deluded enough to think I'd really have become a superstar singer, of course, but I didn't want to risk the loss of my agency and privacy that would come with even a lesser degree of notoriety.

Plus, the idea of someone inviting me to perform somewhere rubbed me the wrong way. Having to play some random piano somewhere, without a chance to check it out first? No, thanks. Having to be at some unknown venue at a certain hour and play for a predetermined length of time? Pfft - I couldn't be hemmed in like that.

At least, that's what I told myself.

So I quit singing in order to spend more time on my new hobby: becoming an alcoholic.

Although sufferers give and give and give to alcoholism, trying to placate it, it only takes. It gives nothing back. Alcoholism ravages everything. It even messes up your throat; your very speaking voice. And accordingly, although I still sang in the car and the shower, I noticed myself getting progressively croakier. My range tightened into that of an alto. Now a regular smoker, too, and still a fan of musical theatre, I'd give out entirely during something like Fantine’s ethereally fierce “Les Misérables" manifesto, “I Dreamed A Dream.”

Oh, sure, every now and then I'd still plonk around on my childhood upright Wurlizter, which lived at my parents’ house. But a devastating injury to my right shoulder and arm, plus a series of surgeries on them that drastically reduced my mobility, put a pretty firm end to that for a long time.

Ten years after that accident, though, I'm a little better than I was - some days, at least. I've been sober for almost 14 years, and I don't smoke cigarettes anymore, either.

One day last year, I had an unusual amount of driving to do. To keep myself entertained when I lost radio reception inside the jagged canyons that mark the line between Riverside and San Bernardino counties, I started singing. Though I hadn't thought about the song in a decade or more, Natalie Cole's rendition of her father’s hit, Nat “King” Cole's “Paper Moon," came out of my mouth.

"But it wouldn't be make-belieeeeeve if you believed in me!” I heard myself belt out, hitting the high note in "believe” with no trouble and still in my chest voice - with breath to spare to ape Natalie's inimitable scatting, although I quickly decided, after a couple of " Ska-dop-BEEP-bop”s and " Shooba-dooya”s, that I probably should not do that. For a couple of reasons.

When I surfaced from the canyons, back in San Bernardino, I pulled over, my body shaky with a flood of adrenaline. What had just happened?! What - why could I sing like that again suddenly? And how? Was it a fluke?

I shuffled through the stacks of sheet music in my mind and chose something else: "I Dreamed A Dream.” Surely I'd choke, as I always did. I pulled out from the gas station where I'd paused and launched into it.

When I got to the climax - the lines where my range and breath had always sputtered and come to a coughing, rasping halt - I found myself pushing through with no trouble at all, completing the ascending phrase:

“As they tear your hope apart /

As they turn your dream to sha-a-a-a-aaaame”

It wasn't that good. It wasn't the sound of angels descending. But it was serviceable! No croaks, no coughs, no slips. If someone kidnapped me at gunpoint and forced me to sing Fantine in a production of "Les Mis” or die, I would live to file a very weird police report.

After a few weeks of further experimentation, I understood that it was not a fluke: Abstaining from cigarettes and alcohol was really giving me back my voice.

I flew back to Indiana to visit my parents a month or so later. My mother had recently taken up piano as a total newbie, and I knew she'd sent my old Wurlizter - already ancient when my parents acquired it in 1992 - up to the great music store in the sky. In its place was an incredibly slick digital piano: a gorgeous instrument and piece of furniture I immediately coveted.

Even though the unaccustomed Midwestern humidity meant my shoulder and arm desperately needed to be oiled à la the Tin Man, I couldn't resist sitting down and launching into “Over the Rainbow." I knew I could sing any song Judy Garland could sing - our ranges are very close - and the thrill of my own little performance sent me straight to Oz.

"I'm really enjoying this piano Mom's got,” I texted Dave. "Maybe we could look for one when I get back?”

He eagerly agreed, then remembered something. "What about that keyboard my dad tried to give us a couple years ago?” he asked. I'd wanted it, but we hadn't had room in our car. "See if he'll give you that again!” he advised.

Awkwardly, I asked my un-laws about it (nope, not a typo; we're not married yet!), and Dave's dad was kind enough to retrieve it immediately, so that I could ship it back to California.

Back home, we set it up. Feeling self-conscious because my playing was incredibly limited to the range of motion I had in my arm at any given time, I plonked away at it, singing softly, when Dave was gone or wearing headphones. That is, until I caught wind of an announcement that the local Civic Theatre would be doing one of my favorite musicals, and auditions were open.

I wasn't sure what kind of room there'd be onstage for someone too lashed by radiating pain to stand up for very long. And any ensemble dancing would be out of the question: My arm simply doesn't move like that. But I wanted to know how I'd sound.

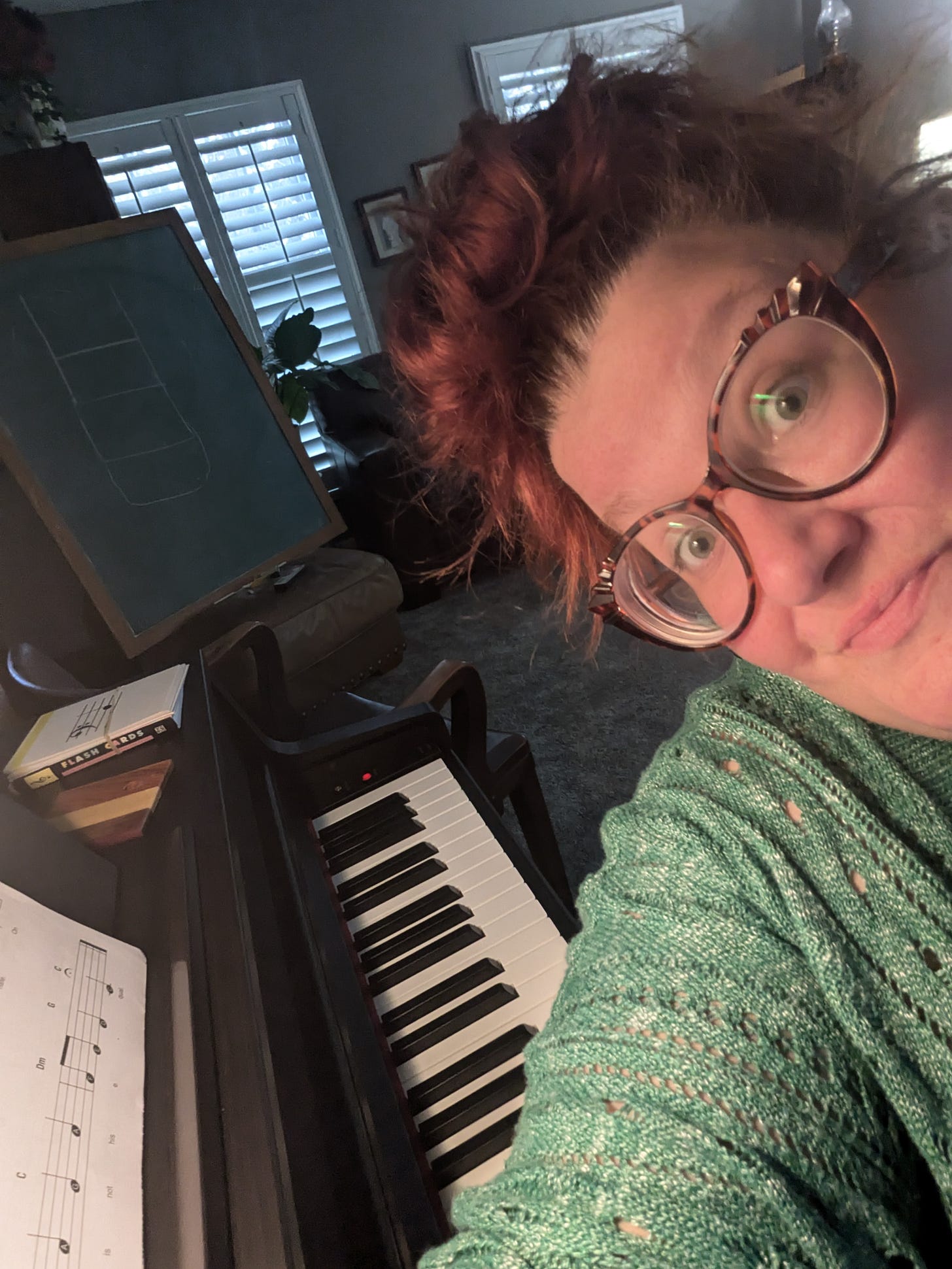

Yesterday, Dave went out to run some errands, leaving me home with Jasmine. Feeling especially motivated after my morning Adderall, I got off the couch and made my way into Dave's domain: the library. But that's also where the keyboard is, so I sat down as Jasmine looked up inquisitively.

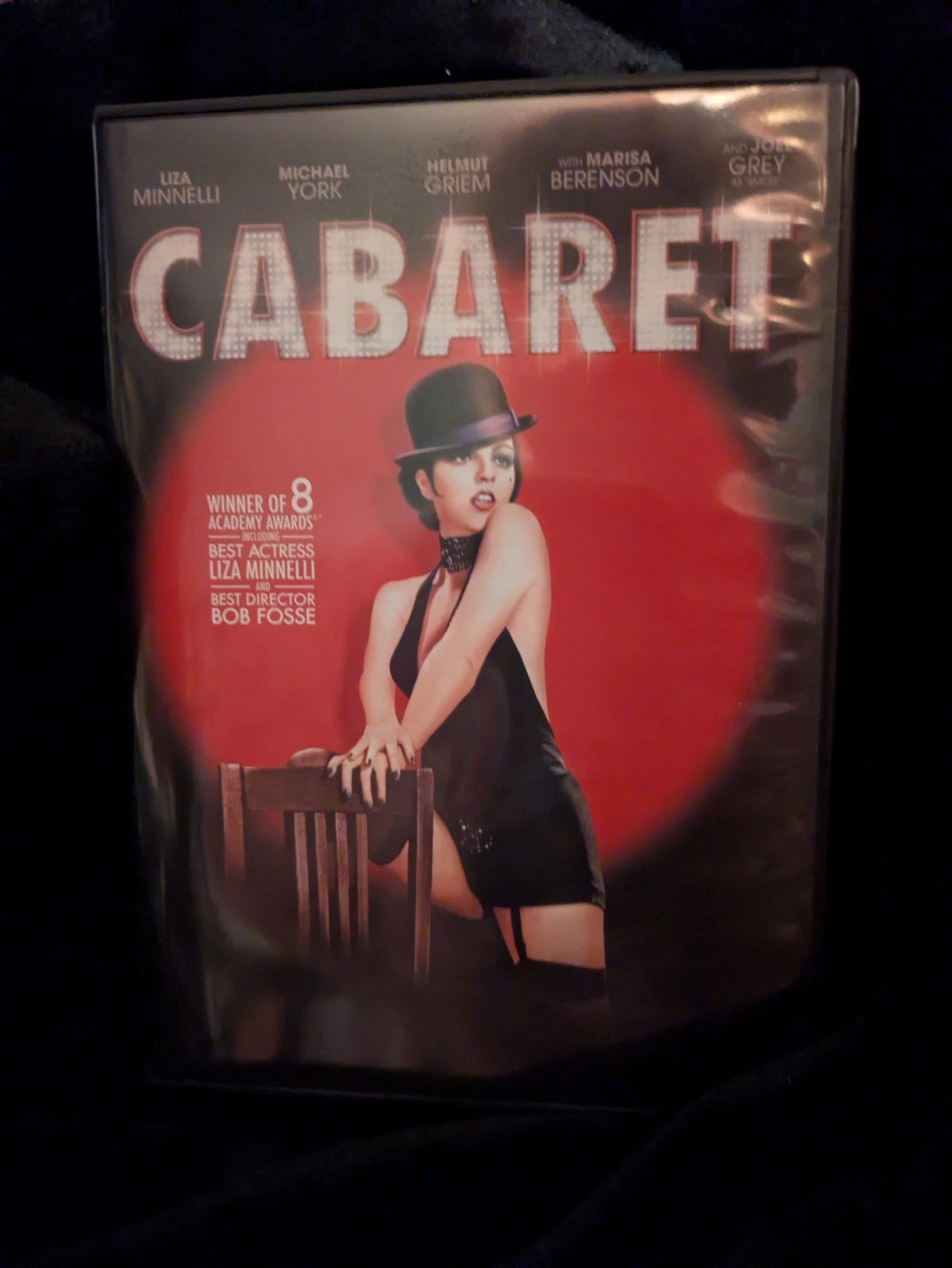

The number-one song for my range is from “Cabaret." “Maybe This Time" is performed to perfection by Liza Minnelli: vulnerable at first, then sexy, slinky, a little sulky, and then, finally, as Minnelli's Sally Bowles finds her confidence, it crescendoes into a radically triumphant staking of her claim.

I began to play. Somehow, I'd never played “Maybe This Time" before, but I knew how it should go and so launched into it, reveling in the at-home feeling of my favorite key - A major. As I went, I found that I was carrying the song pretty well, and in a new voice - one left wine-soaked, smoky, and rich by years of misadventure, but controlled, smooth. And big.

By the time I was belting out

“It's gonna happen /

Happen sometime /

Maybe this time! /

Maybe this time I'll win!”

it just … wasn't me anymore. It was Liza Minnelli - or no, it was Sally Bowles, not Sally Shideler, onstage at Berlin’s Kit Kat Klub in her Japonisme black and white silk hostess pajamas, singing her hopeful little heart out as she embarked upon her doomed romance with fellow expat Brian Roberts, knowing nothing, not any, of what would happen to them there, at that time, in that place, right on the eve of history.

After I held the final, clear "A” of the word “win," accented by the perfect amount of vibrato, I stopped playing and fell silent.

I had goosebumps.

I turned in my chair to see what Jasmine thought. She seemed rather concerned, actually, but before I could feel indignant, my eye caught a flicker of movement out the window. Outside, just thirty steps away, two teenage boys had stopped on the street to listen to me.

“Wow," I heard one say. I saw his friend nod, wide-eyed, and then they began to walk on.

"Wow?” I don't know about that. I just turned 40. I'm not looking to break into anything except publishing. But there is something to be said for using the talents we have, even if just for ourselves - and the occasional passer-by.

At 40, we women are generally told we've expired. We can still be beautiful or interesting or smart, but not in the same way. And just as we’ve gathered enough life and professional experience to start to really excel, we learn with a painful jolt that no one wants to hear what we have to say.

But the cool part of turning 40 is that, while I am now and hope always to be a kind and warm-hearted person, I no longer feel any obligation to behave like that proper young lady I was always trying to be - not that I ever succeeded. Spoiler alert: I can't be a proper young lady! I'm not a young lady anymore, proper or otherwise, so I might as well throw that part out the window, too.

And so, free now of the burden of believing I should be attempting to be perfect - which, again, I sucked at, anyway; trying turned me into an alcoholic - I'll simply do as I please.

Maybe I will try out for a show, handicap be damned! Maybe I won't. Maybe I'll record something for fun, just because I can. Or maybe I'll use this lesson to fully and finally springboard into that other thing I know I really should be doing: writing, and writing seriously.

I'm not sure yet. But I do know

“All the odds are /

They're in my favor /

Something's bound to begin.”

It's gonna happen - happen sometime. Maybe this time!

Good for you! Keep on singing'.

I'd like to hear you do some Phoebe Snow....maybe "Poetry Man"?