A lot can happen in a month. But in March 1917, pretty much everything was happening, and the events of that month affected the course of world history.

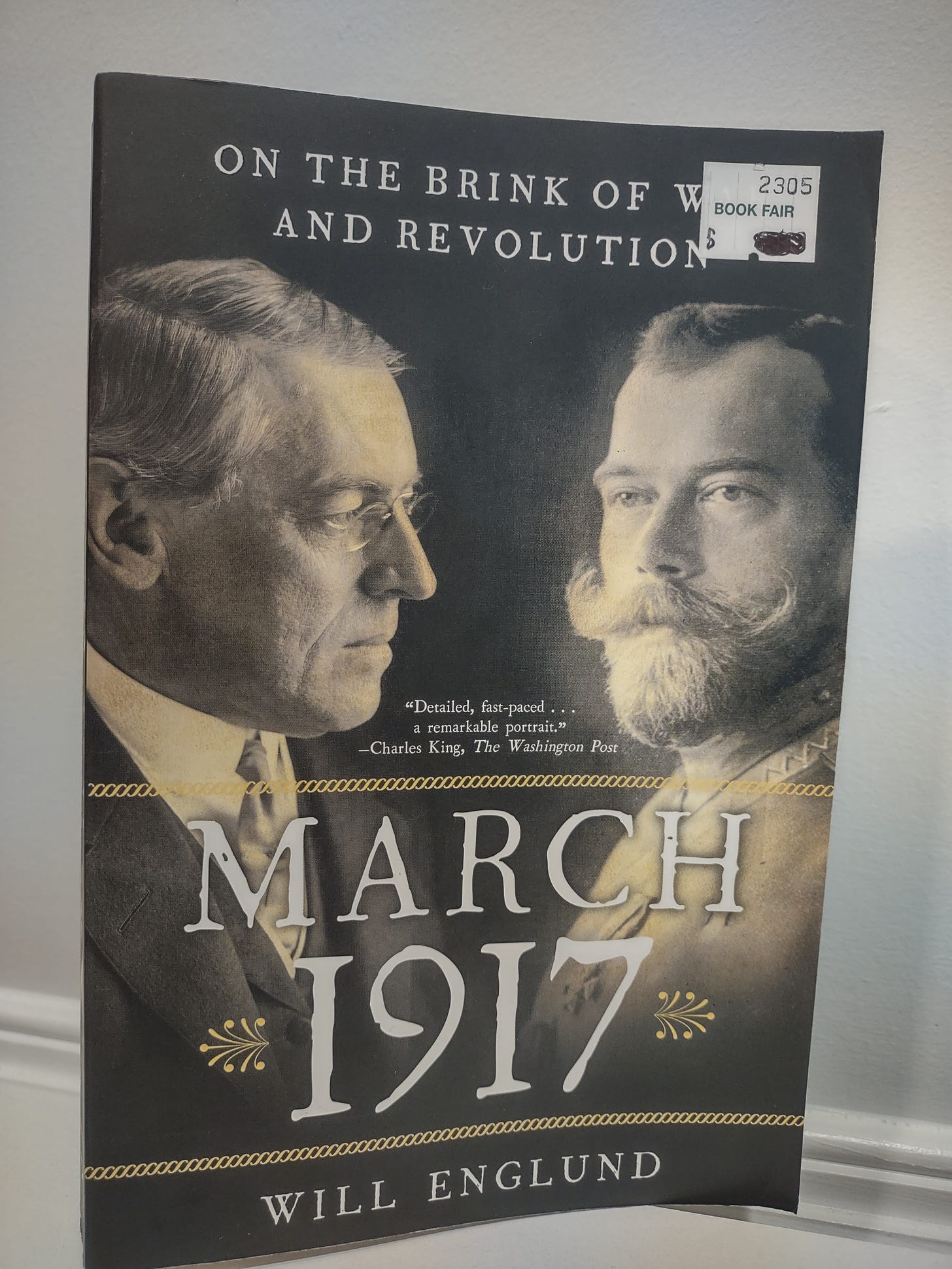

Will Englund examines this pivotal month in his fascinating book, March 1917: On the Brink of War and Revolution.

In this one month:

Nicholas II abdicated the throne, ending three centuries of Romanov rule in Russia, as revolution swept the nation.

Jeannette Rankin, the United States’ first congresswoman, took office as activists continued advocating for the right of women to vote.

As Jim Crow laws continued to oppress, musician Jim Europe believed that he and his fellow African Americans could reduce racial tensions by participating in the war effort.

The U.S. Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the Adamson Act, which established an eight-hour workday and overtime pay for railroad workers.

Writer H.L. Mencken, after reporting from Germany, journeyed to Cuba to report on tumultuous events occurring there.

Germany persisted in its aggressions across Europe and the Atlantic.

President Woodrow Wilson finally abandoned his anti-war stance and prepared to make the case for U.S. entry into World War I, setting a new precedent for American foreign policy.

Englund covers all of this and more in his book, which illustrates how interconnected world history can be.

For instance, the status of Russia initially supplied arguments against the U.S. entering World War I—Americans could hardly make the case that they were fighting for democracy if they were siding with one autocratic nation against another. But then the autocrat stepped down, and many Americans became optimistic about Russia’s future.

Theodore Roosevelt, a strong advocate for American participation in the war, said:

“I rejoice from my soul that Russia, the hereditary friend of this country, has ranged herself on the side of orderly liberty, of enlightened freedom, and for the full performance of duty by free nations throughout the world. … This wonderful change in Russia marches with and is part of the mighty and, I believe, irresistible movement of the whole world to substitute democracy for autocracy in human government …”

For Wilson, if America was going to go to war overseas, it was important to do so in the name of high-minded ideals, not for vengeance or any territorial gains. (Of course, Wilson the high-minded idealist was also Wilson the racist, even by the standards of his time. Englund notes how Wilson segregated the federal workforce, as one egregious example.)

In his speech to Congress asking for a declaration of war, Wilson spoke of Russia:

“Does not every American feel that assurance has been added to our hope for the future peace of the world by the wonderful and heartening things that have been happening within the last few weeks in Russia?”

He added that Russia’s previous autocratic government “was not in fact Russian in origin, character, or purpose; and now it has been shaken off and the great, generous Russian people have been added in all their naïve majesty and might to the forces that are fighting for freedom in the world, for justice, and for peace.”

This speech was delivered April 2, so it’s technically beyond the book’s title, but Wilson crafted it at the end of March, so it counts. This was the speech in which Wilson declared, “The world must be made safe for democracy.”

“We have no selfish ends to serve. We desire no conquest, no dominion. We are but one of the champions of the rights of mankind.”

Englund notes that this line of thinking has influenced every American war since World War II.

And he also gives us this sobering observation:

“Nearly all the arguments about the war turned out to be wrong. It did not make the world safe for democracy, or usher in a new world order, as Wilson had hoped. Roosevelt was wrong in predicting it would smash German militarism. Jim Europe was wrong in expecting it to improve the standing of African-Americans. Mencken was wrong in predicting it would take years to win on the battlefield.”

Englund continues with further examples, and it’s certainly something to keep in mind as we debate contemporary issues. None of us knows as much as we like to think. Look at all those Americans in 1917 who thought wonderful things were just around the corner for Russia.

March 1917 was indeed an eventful, important month. Read the book and see for yourself.