I love a good comprehensive biography, but there’s also great value in picking a moment in time and diving all the way in.

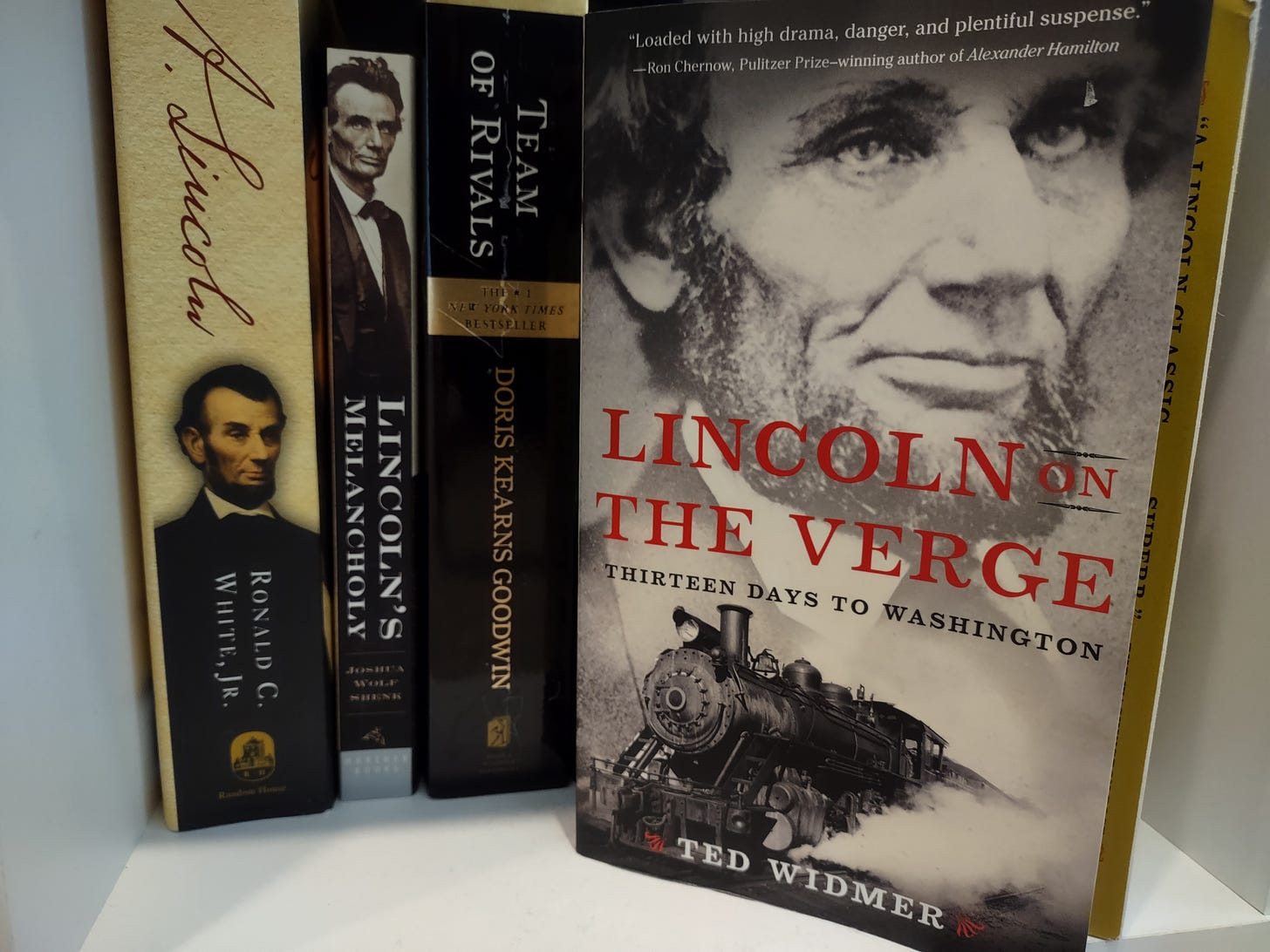

That’s what Ted Widmer does in his excellent book, Lincoln on the Verge: Thirteen Days to Washington. Widmer examines President-elect Abraham Lincoln’s long journey to his own inauguration, in which he needed to steer clear of potential assassination attempts while forging bonds with the people he was elected to serve. Lincoln also had to compete with the Confederacy’s new president, Jefferson Davis, who was embarking on his own journey to take office.

The trip was a monumental odyssey, and Widmer frames it as such, beginning each chapter with a quote from Homer’s Odyssey.

Early in 1861, as the country continued to fracture, Lincoln wasn’t yet the president who would go down in history as one of the best, if not the best. He was still finding his feet and finding his voice, and Widmer shows us how the new president slowly took shape over the course of these eventful days. Occasionally, Lincoln put his foot in his mouth. But other times, he said exactly the right thing at the right time. The incoming president learned and grew.

And all along the way, he needed to shake hands. So many hands. Thousands and thousands of hands, all compressed into a relatively short time frame. The routine gesture turned into grueling exercise before long. Widmer describes it as “a daunting challenge.”

He quotes the author Herman Melville as saying that Lincoln “shook hands like a good fellow—working hard at it like a man sawing wood at so much per cord.”

Widmer writes:

“To look a stranger in the eye and give a firm shake was another act of union, restoring confidence, one clasp at a time. But to multiply it by many thousand times was another Herculean challenge. Lincoln commented privately that shaking so many hands was ‘harder work than mauling rails.’ John Hay compared it to ancient forms of torture: the thumb screw, the rack, and the cap of silence.”

The crowds could be oppressive at times, and a crushing mass of well-wishers posed its own sort of danger. And yet, exhausting though it was, Lincoln seemed to thrive while making these person-to-person connections.

Widmer describes the observations of John Nicolay, Lincoln’s secretary:

“Despite all the obvious reasons for caution, [Lincoln] felt a ‘fascination.’ It did not matter how many there were or where they came from, or whether they were immigrants or not. They were fellow Americans, and ‘he could not easily wrench himself away.’”

Nicolay also observed, as summarized by Widmer:

“It was almost as if an invisible current flowed back and forth, which he compared to electricity. It was a ‘subtle, psychological’ force, spelled out nowhere in the Constitution but essential for the workings of democracy. It began even before he spoke; there was something in his twangy accent and his awkward gestures that worked, paradoxically, in his favor. Nicolay wrote that ‘his whole bearing, manner, and utterance carried conviction to all beholders that the man was of them as well as for them.’”

Some people noticed the strain this was all putting on Lincoln. The presidency lost its glamor to at least one Cleveland reporter, who wrote:

“We do not wish to be President! Whatever our ambitions may have been heretofore, however our bosom may have swelled at the reflection that we should some day reach that exalted station, still we say that we no longer aspire to the office. We have seen enough of what it is to be President to effectually quench any ambition that we may have been inspired by prophetic words of the past. This reporter declines to run.”

Not everyone shared that sentiment, though. Lincoln’s journey took him past several presidents, past and future, including a young law clerk named Grover Cleveland, who went on to become the 22nd and 24th president, forever muddying our presidential counting system.

By the time Lincoln reached New Jersey, his ideas and vision were coalescing. Widmer writes [emphasis in the original]:

“Lincoln then made a promise of his own: that the Union would be ‘perpetuated’ in accordance with ‘the original idea’ of the Revolution. In other words, he would not become the president of a half country, or even worse, a country with a half-baked understanding of its history. On the contrary, he would insist that the original idea be remembered. He would do all he could to uphold the principles of republican self-government and the Declaration’s thundering chorus of equality.”

The New York Herald reported on Lincoln’s safe arrival in D.C., noting that over 12 days, Lincoln journeyed 1,904 miles along 18 railroad lines and through eight states, during which he gave 101 speeches, at minimum.

“By his words, and his physical presence, he had shored up America’s flagging belief in her institutions. Millions of Americans had glimpsed a top hat parting a sea of humanity, or seen a bearded man wave from the back of a speeding train, or bow from a hotel balcony, and felt a connection to their government. Most had never seen a president, and never would again.”

There’s much more I haven’t touched on. Read the whole epic odyssey.