Lincoln, the Declaration of Independence, and continuous improvement

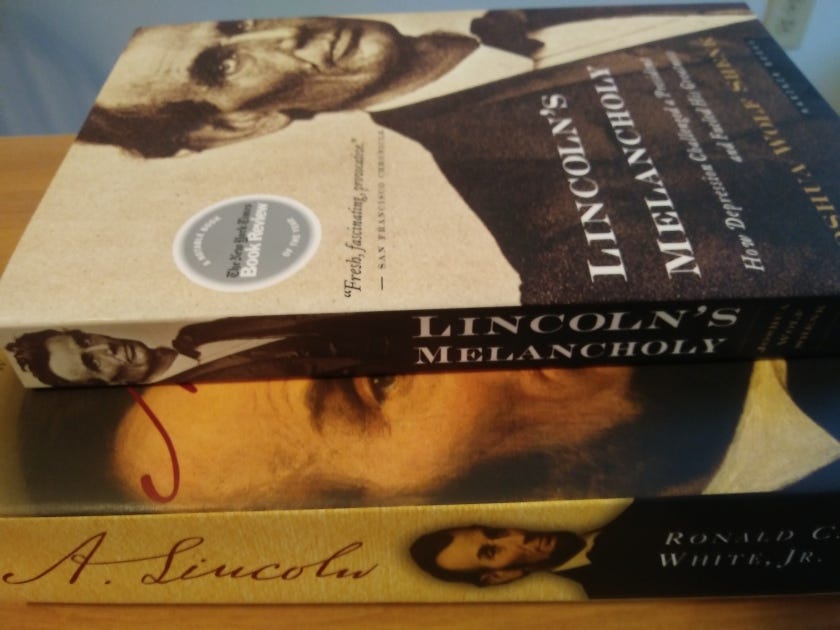

Considering two biographies of the Great Emancipator

Abraham Lincoln improved the Declaration of Independence.

He didn’t revise a single word of it. He didn’t need to. The words were always correct. The introduction, in particular, is timeless. But he expanded the scope of whom the words applied to.

The Declaration states, “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”

Obviously, when this was written and adopted, the American colonies did not practice what the document preached. It’s easy to point the finger back through history and pass judgment on the glaring hypocrisy of a slaveowner writing these words, as well as on the failure of the Founding Fathers to eradicate slavery as they secured greater freedoms for themselves. And criticism is absolutely deserved.

But we also need to remember the full historical context of the culture the Founding Fathers inherited and the improvements they made within it. They did what they could, and subsequent generations would need to take the next steps.

Lincoln understood that. When he argued against slavery in the 1850s, he didn’t self-righteously blast the Founders for their failures on the issue. Rather, he noticed the torch they dropped, picked it up, and ran it down the next leg of the relay, even while many didn’t want him to.

Slavery’s defenders and apologists attempted to downplay the importance of the Declaration of Independence. They dismissed the notion that “all men are created equal” as either flat-out wrong or as intended to refer only to white men.

As Ronald C. White Jr. writes in the biography A. Lincoln, “For many Whigs, the Declaration became noteworthy chiefly as a historical signpost. This view, as Lincoln well understood, defused the Declaration as an impetus for reform in mid-nineteenth-century American life.”

So Lincoln, instead, helped reassert the importance of that document, elevating the ideals it espoused and pointing out how broadly they applied.

“The assertion that ‘all men are created equal’ was of no practical use in effecting our separation from Great Britain,” Lincoln said, as quoted in Lincoln’s Melancholy by Joshua Wolf Shenk, “and it was placed in the Declaration, not for that, but for future use. Its authors meant it to be, thank God, it is now proving itself, a stumbling block to those who in after times might seek to turn a free people back into the hateful paths of despotism. They knew the proneness of prosperity to breed tyrants, and they meant when such should re-appear in this fair land and commence their vocation they should find left for them at least one hard nut to crack.”

Lincoln was not as enlightened on racial issues as we would have liked. Though opposed to slavery, he did not believe in full social equality. Still, he was ahead of the curve compared to many of his contemporaries, and that should not be dismissed.

White quotes Lincoln as saying, “I think the authors of that notable instrument intended to include all men, but they did not intend to declare all men equal in all respects. They did not mean to say all were equal in color, size, intellect, moral developments, or social capacity.”

But, Lincoln went on to say, the Founders did declare that all men were created equal in terms of the inalienable rights listed in the document: life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

“There is no reason in the world why the negro is not entitled to all the natural rights enumerated in the Declaration of Independence, the right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. I hold that he is as much entitled to these as the white man,” Lincoln said, as quoted in Lincoln’s Melancholy.

According to Shenk, Lincoln said that the Founders were hostile to the principle of slavery and tolerated it only by necessity.

As Shenk writes, “The Founders recognized the evil, Lincoln said, and made accommodations to restrict it, believing that the very experiment in liberty could be spoiled if they acted to end it too quickly.”

Shenk adds, “The spirit of the Declaration, Lincoln said, was meant to be realized — to the greatest extent possible — by each succeeding generation. The Founders cast off despotism and created the framework for a free republic, invoking, as they did, not arguments of mere self-interest but the ideal of natural, universal, God-given rights.”

“They meant to set up a standard maxim for free society, which should be familiar to all, and revered by all; constantly looked to, constantly labored for … even though never perfectly attained,” Lincoln said.

Lincoln’s focus was not on perfection but on improvement, something he practiced in his own life as he rose from humble origins.

The Founders were not perfect, not by a long shot, but they improved the world around them. The world required further improvement. Lincoln, also far from perfect, achieved significant milestones with the Emancipation Proclamation and his leadership in defeating the Confederacy, and he knew there would be still further improvement needed after his time, and for all time.

“That is the issue that will continue in this country when these poor tongues of Judge Douglas and myself shall be silent,” Lincoln said during an 1860 debate, identifying the issue as “the eternal struggle between these two principles—right and wrong—throughout the world.”

Lincoln continued, “They are the two principles that have stood face to face from the beginning of time; and will ever continue to struggle. The one is the common right of humanity and the other is the divine right of kings. It is the same principle in whatever shape it develops itself. It is the same spirit that says: ‘You work and toil and earn bread, and I’ll eat it’” (A. Lincoln, White).