Lenin’s Red Flag

A Review of a biography telling the story of one of the 20th century's most evil men

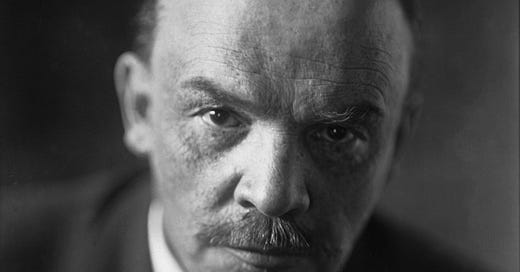

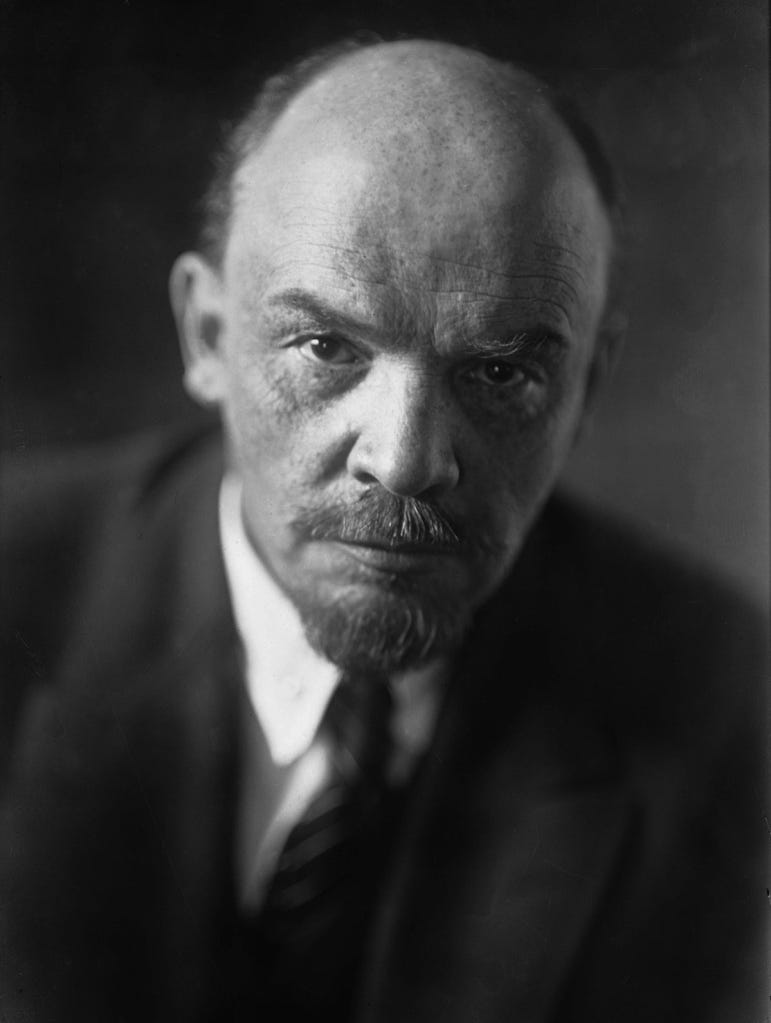

Vladimir Lenin was the sort of person who should never, ever have been given any power. His ruthlessness during the Russian Revolution makes that clear, but he foreshadowed his cold-blooded disregard for human life much earlier.

In 1891-92, Russia’s Volga region experienced its worst famine in many years. According to Victor Sebestyen in his biography Lenin: The Man, the Dictator, and the Master of Terror, more than 400,000 people died over the course of the famine, either starving to death or contracting typhus or cholera.

“The central government did almost nothing to help the millions of starving peasants who poured into the towns begging for food,” Sebestyen writes.

This was, of course, not yet Lenin’s government. (And he wasn’t yet calling himself Lenin, but I’ll use that name here for simplicity’s sake.) Nevertheless, as a private individual, Lenin showed no sympathy for the famine’s victims. Relief campaigns were launched, but he had no interest in such efforts.

“For him the important thing was that the famine would weaken the autocracy and might further the cause of the Revolution. The thousands of people who died of hunger were simply unfortunate casualties of a war against Tsarist oppression,” Sebestyen writes.

Lenin was pretty much alone in this line of thinking. His callousness disturbed even his sisters, who were normally supportive of him.

His sister Maria is quoted as saying, “Vladimir Ilyich, it seems to me, had a very different nature from Alexander Ilyich [their late brother]. Vladimir … did not have the quality of self-sacrifice even though he devoted his whole life indivisibly to the cause of the working class.”

Sebestyen says, “He would shrug off accusations that he was inhumane, using an inflexible logic and a cold interpretation of Marxism which Marx himself would never have countenanced.”

He goes on to quote Lenin as saying, “It’s sentimentality to think that a sea of need could be emptied with the teaspoon of philanthropy. The famine … played the role of a progressive factor.”

After Lenin gained power, another food shortage occurred in 1918. The Bolsheviks didn’t cause the problem, but they, led by Lenin, amplified the pain and suffering.

Sebestyen notes that there were very few rich peasants in Russia at the time, but that didn’t stop Lenin from using them as scapegoats. The dictator branded rich peasants as “kulaks” and accused them of hoarding grain and starving Russia on purpose.

“The kulaks are the rabid foes of the Soviet government … these bloodsuckers have grown rich on the hunger of the people. These spiders have grown fat out of the workers. These leeches have sucked the blood of the working people and grown richer as the workers in the cities have starved. Ruthless war on the kulaks! Death to all of them,” Lenin said in a speech.

Lenin first expected the peasants to sell their grains to the government at an insultingly low price. The peasants, naturally, refused. So, Lenin established the Food Commissariat and unleashed armed requisition brigades on more than 20,000 villages within a couple of months.

As Sebestyen describes it, the brigades engaged in brutality—torturing peasants, stripping them, sometimes even killing them. One Bolshevik official compared the brigades’ work to “a medieval inquisition.”

Some Bolsheviks worried that the brigades were too harsh, to the detriment of the party’s reputation. Lenin did not relent.

Lenin’s instructions to Bolshevik chiefs illustrate a toxic combination of heartlessness and ruthlessness:

“Comrades, the kulak uprising in your five districts must be crushed without pity. The interests of the whole Revolution demand it, for the final and decisive battle with the kulaks everywhere is now engaged. An example must be made. 1.) Hang (and I mean hang, so the people can see) not less than 100 known kulaks, rich men, bloodsuckers. 2.) Publish their names. 3.) Identify hostages … Do this so that for hundreds of miles around the people can see, tremble, know, and cry: they are killing and will go on killing the bloodsucking kulaks.”

In a postscript, Lenin added, “Find tougher people.”

According to Sebestyen, at least 3,700 were killed during the first year of food requisitions, and some villages were burned down. These extreme measures had little effect on the overall problem, and yet they set a terrible precedent.

He writes that “campaigns against the kulaks and forcing farmers at gunpoint to produce for the State became a feature of Soviet life for decades to come.”

Anyone who perceives utility in human suffering can’t be trusted to wield power with the necessary humility and compassion. Whatever good intentions Lenin may have had for Russia’s future, he quickly invalidated them with his willingness to dispose of people for his ideological cause.

In hindsight, the warning signs were there years before his ascension.

Daniel Sherrier is a writer living in central Virginia. A William & Mary graduate, he worked for community newspapers for nearly a decade as a reporter and then an editor. He is the author of the superhero novels The Flying Woman and The Silver Stranger, and he overthinks stories and writing on his own Substack. He is NOT a historian, but loves reading about history and sharing interesting books.