Scientific exploration was part of the rationale for the Belgica’s mission. Adrien de Gerlache, a Belgian naval officer, dreamed of earning glory for his nation. He wanted to lead the world’s first expedition to the magnetic South Pole. And they wouldn’t just get there—they’d study it and report their findings, adding to the world’s base of scientific knowledge.

But thanks to de Gerlache’s overzealous ambition, the Belgica became trapped in ice and forced to endure a long Antarctic night. The sun set on May 16, 1898, and wouldn’t return until July 22 that summer, transforming the expedition itself into a science experiment: What happens when you deprive men of sunlight for weeks on end?

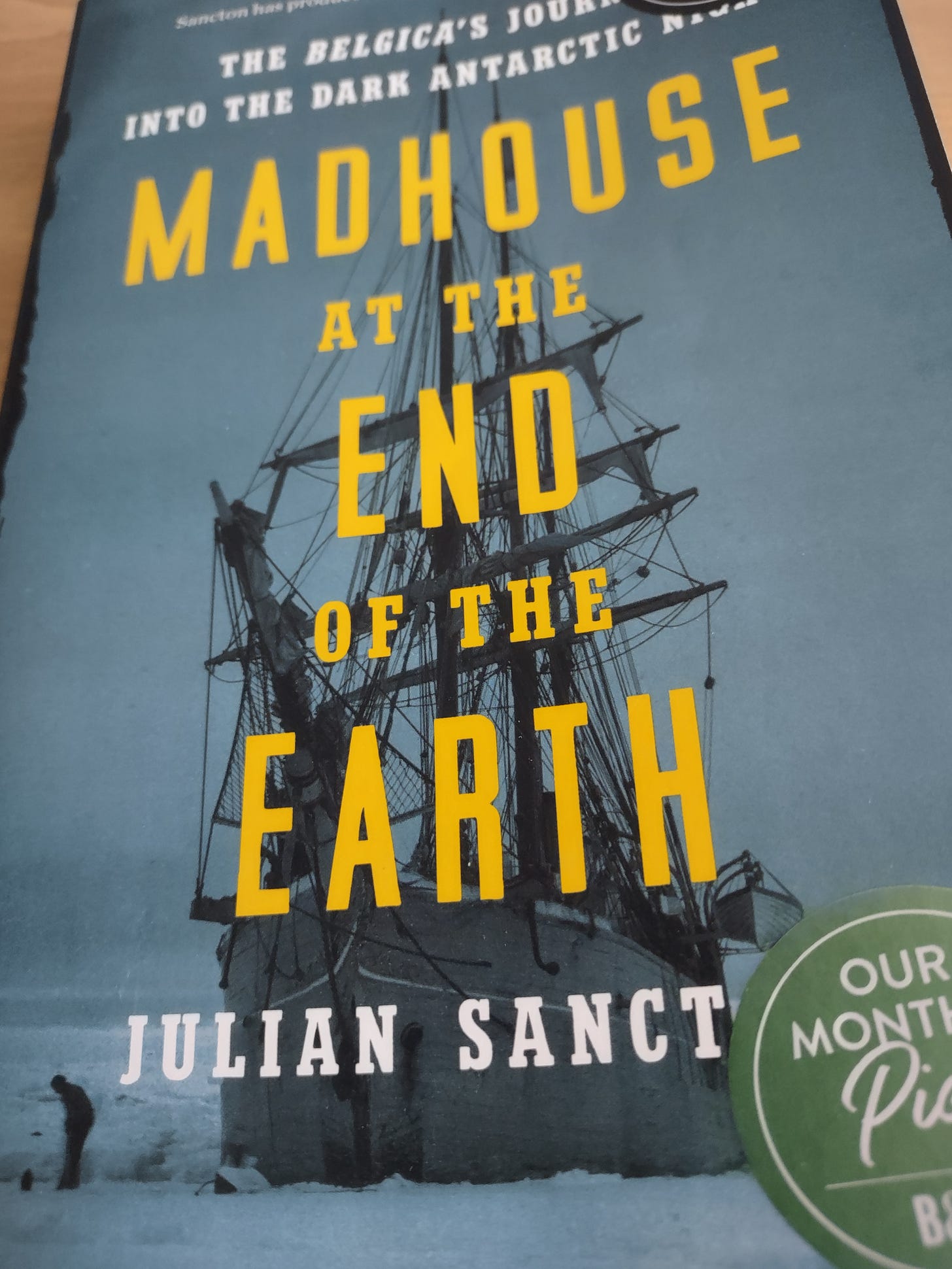

Julian Sancton describes the ordeal, and the entire voyage, in the excellent Madhouse at the End of the Earth.

“The disappearance of the sun deprived the pack of life. Almost all carbon-based life forms are sun-eaters. Man eats the cow that eats the grass that draws energy from the sun to absorb minerals from the earth with which to build organic matter,” Sancton writes.

Among the mostly Belgian and Norwegian crew was an American doctor, Frederick Cook, who went into full problem-solving mode once he noticed the concerning symptoms.

Depression struck first, which was also a product of the isolation and constant danger, but the downturn accelerated once the sun departed. Then, the men began to physically break down.

Cook wrote down his observations: “All seem puffy about the eyes and ankles, and the muscles, which were hard earlier, are now soft. The skin is unusually oily. The hair grows rapidly, and the skin about the nails has a tendency to creep over them, seemingly to protect them from the cold.” He added that “we became pale, with a kind of greenish hue.”

Headaches and insomnia were on the rise, and even those who slept for nine hours remained lethargic. Heart rates spiked with even minimal exertion, and at other times they dipped to frighteningly low levels, as little as forty beats per minute.

Cook observed, “The sun seems to supply an indescribable something which controls and steadies the heart. In its absence it goes like an engine without a governor.”

One crew member, Emile Danco, was especially vulnerable due to preexisting heart trouble. He died during the long night, further demoralizing the survivors.

The men soon struggled to concentrate and grew more irritable. At one point, a few of them heard horrific screaming and went to investigate. They never did discover the source.

Henry Arctowski, a Polish scientist on board, summed up the general atmosphere: “We are in a mad-house.”

“Like a medical detective, the doctor [Cook] now dedicated all of his time to determining the causes of the general malaise that plagued the ship during the long night,” Sancton writes.

Cook’s observations led him to conclude that humans were every bit as dependent on sunlight as plants were. In the absence of any better light source, he had the men stand naked in front of a roaring fire, which he dubbed a “baking treatment.” Sancton notes that this was an early form of light therapy. Participants showed some improvement, though it was far from a cure.

Cook also prescribed exercise in the form of walking around the ice for an hour a day—the “ ‘mad-house’ promenade,” as it became known.

Symptoms mounted nevertheless, prompting Cook to suspect scurvy, which had claimed the lives of numerous sailors in earlier eras but hadn’t been seen nearly as much in modern times. Fruits and vegetables, the best remedy, weren’t an option, but meat was—primarily penguin meat, and also some seal meat.

As Sancton explains, humans could benefit from the ascorbic acid within the animals and stave off the effects of scurvy, provided the meat was eaten in sufficient quantities and wasn’t overcooked.

Penguin was certainly an acquired taste, but the men who ate it showed the most significant improvement, while those who resisted—including de Gerlache—continued to spiral. Sancton notes that it didn’t eliminate all suffering, but it kept the crew of the Belgica going until the sun returned and they could begin plotting their escape.

Madhouse at the End of the Earth is a fascinating read, full of adventure both physical and psychological.

Daniel Sherrier is a writer living in central Virginia. A William & Mary graduate, he worked for community newspapers for nearly a decade as a reporter and then an editor. He is the author of the superhero novels The Flying Woman and The Silver Stranger, and he overthinks stories and writing on his own Substack. He is NOT a historian, but loves reading about history and sharing interesting books.