Long ago, I was an assistant manager at a clothing store. For reasons that were never sufficiently explained, whenever I completed a refund transaction, I had to get the signature of one of the other employees—in addition to my own and the customer’s, resulting in a most impressive triple-signature document.

One day I asked a 21-year-old co-worker to sign one of those receipts, and she said, “All right, I’ll give you my John Hancock.” Then she stopped and thought for a moment, wondering aloud, “Why do they call a signature a John Hancock?”

I immediately responded, “John Hancock was the first person to sign the Declaration of Independence, and he signed it really large.”

She laughed, clearly not expecting anyone to actually know such a thing. “OK, nerd.”

(And I didn’t even mention that the guy presided over the Continental Congress, or that he’s a character in the hit Broadway and motion picture musical 1776.)

My response—and, I believe, valid question—was, “But wait, who doesn’t know who John Hancock is?”

Naturally, this led to a poll among the other employees who happened to be there. To my dismay, only two others were familiar with the late Mr. Hancock. One was a friend of mine from William & Mary, thereby doing nothing to dispel the “nerd” allegation. In fact, that was the rebuttal: “Oh, well, you two went to the nerd school.”

So we were apparently disqualified. The other was a high school junior whose history class had only just covered the Revolutionary era.

The high school boy answered, “Oh! He signed his name big enough that the king could read it without his spectacles!” That may just be a myth, but close enough.

There were several others working that day, all in the teens through 20s range. None of them had the slightest clue who the man was, and they were all astonished that anyone would know this seemingly random piece of trivia.

I may have been ahead of the curve by knowing an entire thing or two about Hancock, but I didn’t know nearly enough.

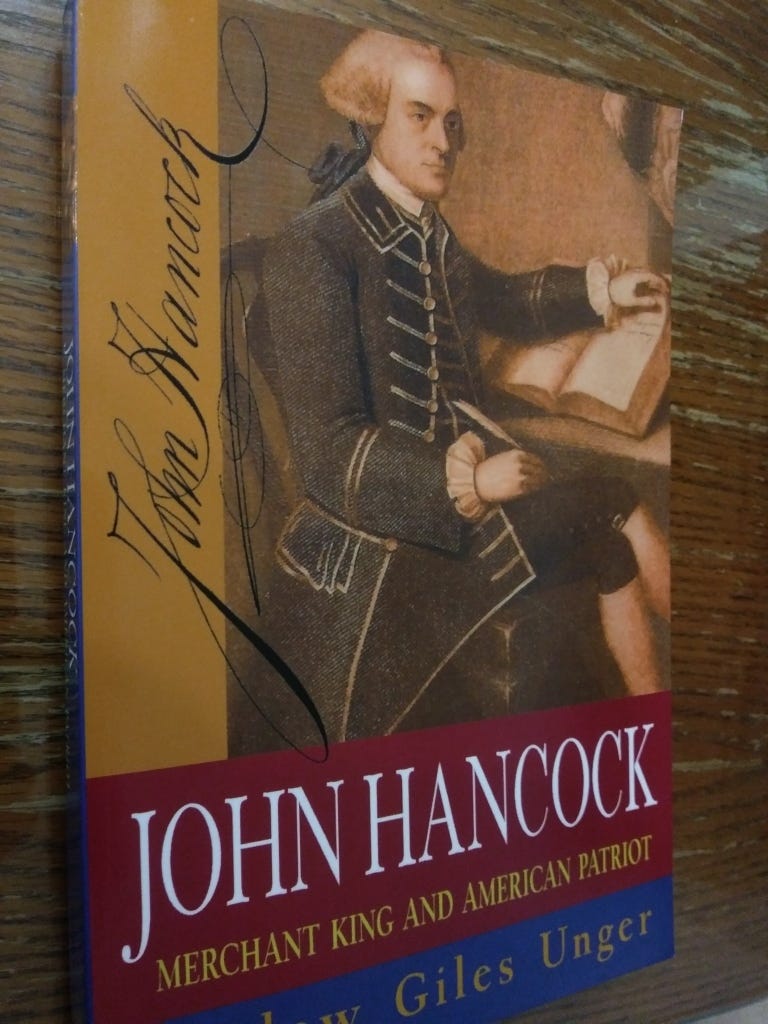

Recently, I read a full biography on the man in question, John Hancock: Merchant King and American Patriot by Harlow Giles Unger (2000). Turns out, Hancock is much more than a signature. He was an important figure leading up to the American Revolution, and as president of the Continental Congress from 1775 to 1777, he was essentially the first chief executive as the colonies adopted the Declaration of Independence—in a sense, the first proto-president of the United States of America.

According to Unger, what made Hancock indispensable as the Continental Congress’s president was his skill as a moderator, which he honed at Boston town meetings, in the Massachusetts House of Representatives, and at the Massachusetts Provincial Congress.

“In all three, he had often reconciled Tories with Whigs, radicals with conservatives, and rural interests with urban interests. Congress elected John Hancock unanimously. He considered his election as president of Congress the greatest honor of his life,” Unger writes.

Impartiality was vital to his role as president, and his neutrality earned him the respect of the delegates.

Unger says, “He was the perfect president, with some appeal to all factions but favoritism to none. He understood everyone’s point of view. His experience as moderator and legislator appealed to moderates; his wealth, business position, and education appealed to conservatives; and his defiance of British authority in Boston appealed to radicals. And what appealed to all was his vast experience directing a large organization, namely the House of Hancock.”

Unger emphasizes the importance of Hancock’s broad appeal, as the states were anything but united before the Declaration.

Additionally, after the delegates voted on each matter, the task of executing fell to the president, as did the responsibility of communicating with the leaders of each colony.

Hancock had to “supervise the acquisition, collection, and shipment of money, arms, and ammunition that Congress approved for transfer to the army. Congress legislated, but President Hancock executed,” Unger writes.

Also, Hancock’s wasn’t merely the first signature on the Declaration of Independence. For about a month, his signature was the only one on the document, and “it constituted tangible evidence of treason that would have cost him his life if he had been captured,” Unger says.

One of his final accomplishments as president was helping guide the Articles of Confederation to adoption. Though far from perfect (as we now know with our historical hindsight), the Articles were a necessary stopgap measure at the time.

“His imminent departure evidently forced delegates to recognize how important his mediative skills had been in holding Congress together. Without him, many delegates would have deserted and shattered the unity essential to effective prosecution of the war. In his absence they would need a contract to bind them together,” Unger says.

So that’s a little more about Hancock, and that’s still just a glimpse of the man behind the signature. Read Unger’s book for a more thorough portrait.

Daniel Sherrier is a writer living in central Virginia. A William & Mary graduate, he worked for community newspapers for nearly a decade as a reporter and then an editor. He is the author of the superhero novels The Flying Woman and The Silver Stranger, and he overthinks stories and writing on his own Substack. He is NOT a historian, but loves reading about history and sharing interesting books.