It's already slipped out of the news cycle a little bit, but on September 4, our nation suffered yet another school shooting. This time, the gruesomely familiar scene unfolded at Apalachee High School, in Winder, Georgia, a small town about an hour east of Atlanta.

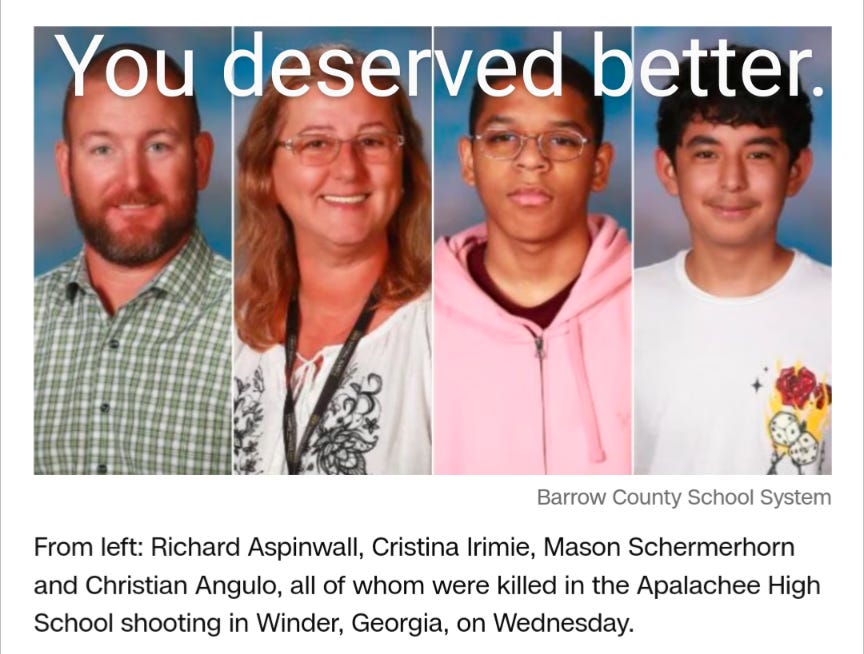

The shooter was a 14-year-old boy who had already had a previous run-in with the FBI in 2023 for bragging online about his plans to carry out a school shooting in the future. I'm not going to name him. He killed four people: two students, Mason Schermerhorn and Christian Angulo, and two teachers, Richard Aspinwall and Christina Irimie, and he injured nine more.

Remarkably, this shooter did not die in the melee, neither by his own hand nor in a suicide-by-cop, as most school shooters do. This shooter will live to be held accountable - even as we cluck and wring our hands about what kinds of lifelong punishments are appropriate for a 14-year-old child.

For it seems that the shooter has had a difficult time in his short life. It has been written that he was a victim of bullying. We've also learned that his mother, Marcee Gray, has a criminal record that extends back to before his birth, and which placed her in jail as recently as April of this year. The shooter's father, Colin Gray, was said to be emotionally abusive, and we know it is true that repeated abuse of any kind can sap every last bit of a person's humanity, leaving behind only a vengeful husk.

In America, we like to analyze points like these. We like to isolate and trumpet out the real problem: something strange, anything odd that could explain each senseless tragedy - except for the guns themselves. It's never the guns.

Hey, I don't make the rules.

And yes, of course: irresponsible, mentally-ill, addicted, or generally dysfunctional parents can harm their children in many ways. In the tragedy at Apalachee High School, this truth was highlighted with the news that the gun the shooter used to murder his teachers and classmates had actually been given to him as a Christmas present from his dad. Incomprehensibly, this gift was given after the episode with the FBI.

We've started to see some accountability for such inscrutably fatal lapses in parental judgment around their children's access to guns. For instance, earlier this year, Jennifer and James Crumbley were each convicted of involuntary manslaughter and sentenced to ten years in prison for their roles in facilitating their son's 2021 shooting at Oxford High School in Michigan. Robert Crimo, Jr., of Illinois and Deja Taylor, in Virgina, have also both been incarcerated as results of the public shootings their respective kids committed.

Now, Colin Gray joins their ranks as he finds himself in custody, too, for his part in providing his child with the instrument of war he used to murder two classmates and two teachers.

But what if Colin Gray hadn't been able to get his son a gun so easily? What if it hadn't been so easy for the shooter to access his gun? What if Colin Gray just hadn't been able to provide his child with a dedicated in-home firearm, just one fucking month after meeting with FBI and sheepishly explaining to the agents that his son was just talking big on Discord - that he certainly wasn't a school shooter in the making?

In fact, what if there were a couple of things the American public could decide to do that would reduce the number of these incidents? Despite the stranglehold that firearm ownership has on our national identity, what if a majority of us decided they should be handled with just a little more care - for everyone's sake?

Come on: It should be easy to agree that even one school shooting is too many. School shootings snuff out young lives that have barely had the chance to bloom. School shootings take away caring adults who voluntarily engage in notoriously high-pressure and demanding work for laughably insufficient pay, just for the love of teaching and guiding children. These are people we need more of, not fewer. School shootings terrify everyone who’s even remotely connected to the communities they happen in, and those who are lucky enough to live through the event are often scarred for life.

But to be very clear, as awful as they are, school shootings are statistically quite rare. When we hear of these events, we forget about all the days when nothing like that happens. To us, the news-consuming public, it can seem like school shootings happen “all the time," but that's just not true.

What does happen all the time, though, is gun violence.

I refer here not just to school shootings, but also to suicides, intentional murders, drive-by gang feuds, and even hunting and gun-cleaning accidents. (See also: "War.”) The Pew Research Center tracks this stuff, and in 2021, the most recent year with complete data, 48,830 Americans died by gunshot.

That's 133 people dying every day as a result of firearms.

Once again, I ask: What if it just weren't so goddamn easy to die by guns? At school, at the mall, at the park, in the office parking lot, in your car - what if it were harder to take such an irreversible and violent action with the flick of a trigger?

At this point, I need to shift gears and tell you why I'm not trying to take away your guns.

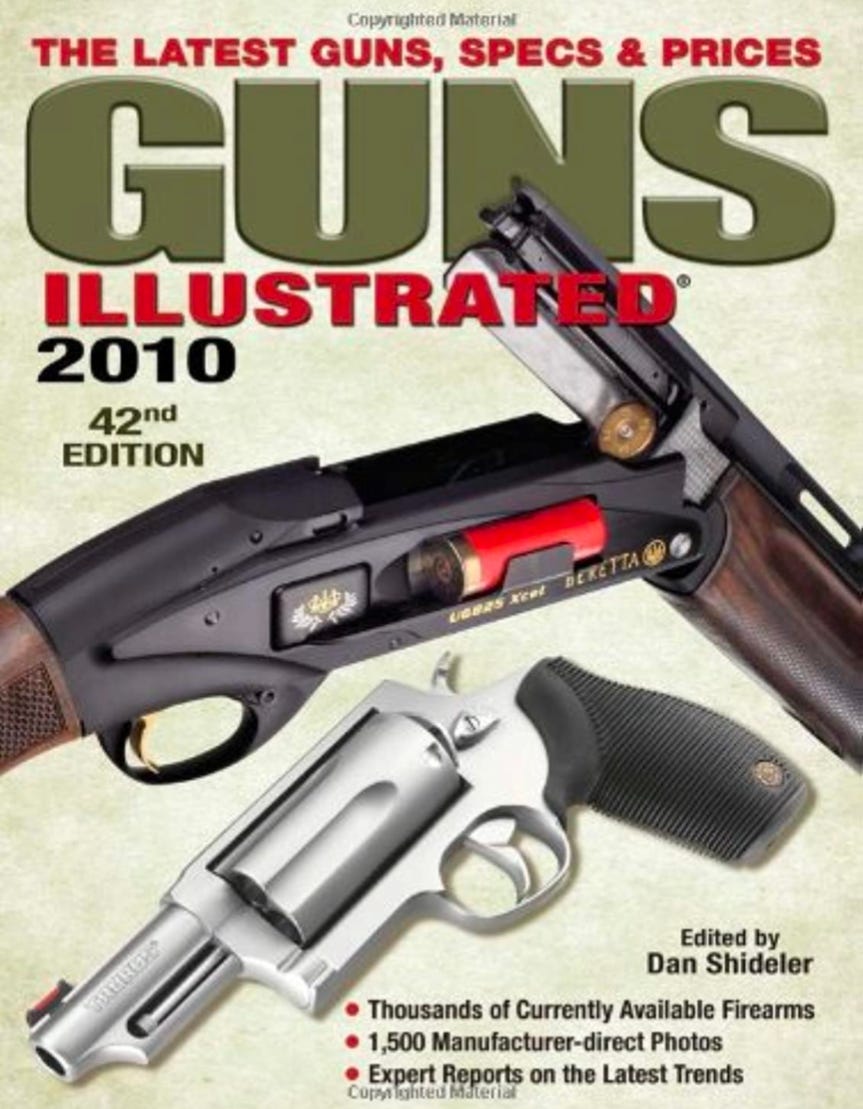

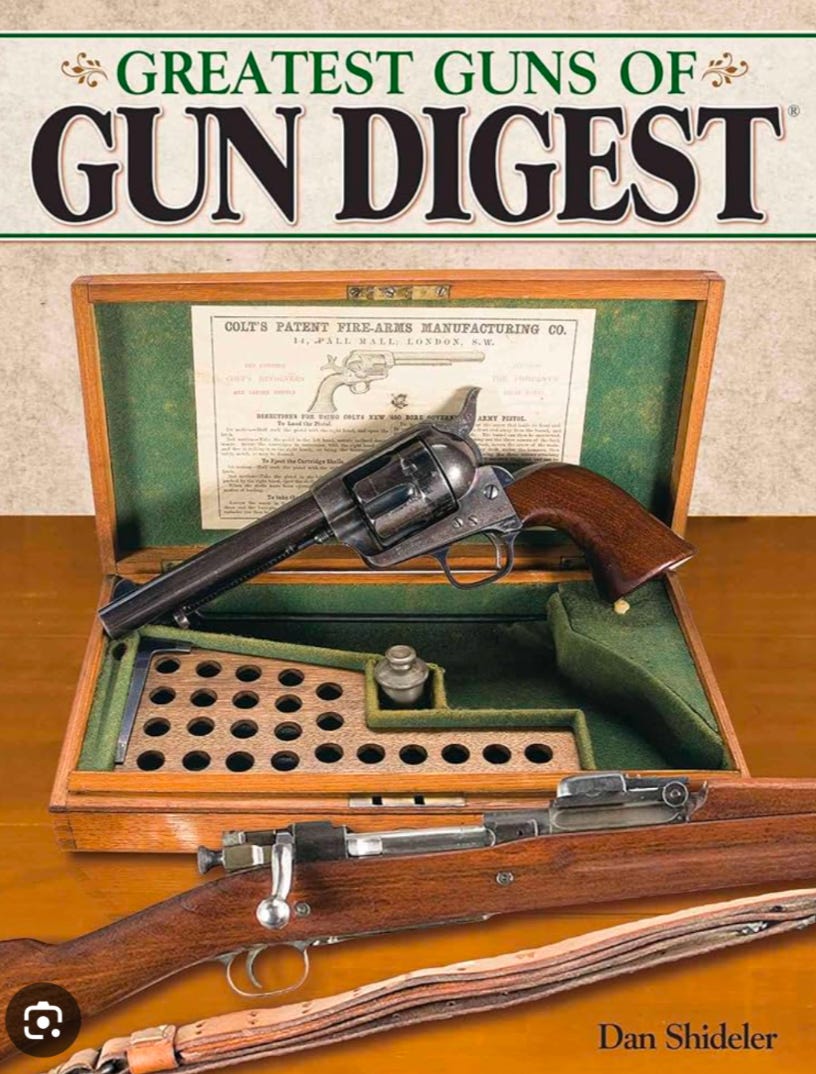

I grew up with a most unusual father. Only two other people in the world know exactly what this dude was really like as a father, and we still surprise each other with anecdotes about him that the others had never heard. But one thing most people knew about our dad was that he was a gun guy. In fact, if you'll indulge me for a moment, my father was the gun guy for many years prior to his death in 2011.

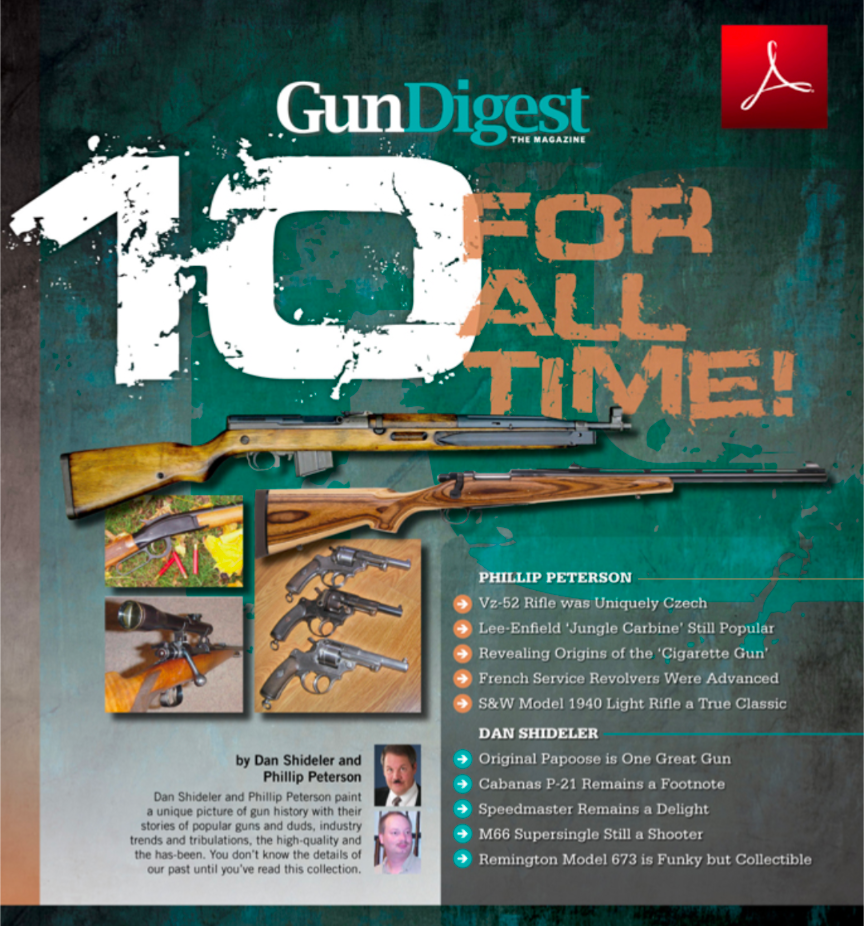

Google the name "Daniel M. Shideler," and you'll find the collected output of a little boy who grew up in the sepia-tinted northern Indiana of the 1960s. It was Jean Shepard country, and accordingly, my dad passed his time emulating his own father in all manly pastimes of the day, including shooting. In between hunting trips to our family's private forest and campground in Michigan, Dad pored wistfully over my grandpa's issues of "Gun Digest," the definitive catalog for the discerning firearms enthusiast. With his big brother, he'd pass hours circling the guns he'd make sure to buy someday, when he grew up.

And he did. In fact, he grew up to become the editor of that publication - the gun collector's bible - as well as innumerable other titles, including another indispensable volume, “The Standard Catalog of Firearms.” He was a hunter, a shooter, a collector, a dealer, a trader, an educator - a true lover of firearms.

And he was also a freak for gun safety. He treated them reverently and locked them up without fail. Trying to teach me to shoot one day, he clocked my extreme nervousness and excused me after one shot, when the kick knocked me right on my ass. He recognized that my nervousness made me a serious liability, so he moved on to teaching my brothers, who showed much more aptitude: they treated the instruments respectfully, but not fearfully.

And as a result of Dad's influence, I grew up understanding that guns themselves were actually pretty safe, reliable machines. Nearly without exception, the problems come from the human error of the user. “Any time you pick up a gun, you need to understand that someone or something may end up dead," he said over and over.

And he was right. Whether it's inappropriate access, ineptitude, cavalier handling, or an active decision to harm someone, gun deaths come from the people using, misusing, or abusing these instruments.

There's a saying: "Guns don't kill people. People kill people." It's true that a gun, unlike, say, a tiger, a tornado, or a gas leak, is not a threat until a human touches it. Nevertheless, a lot of people do seem to use guns to kill themselves and other people. I believe guns make killing easier than it would be if other means were required instead - especially killing at scale.

So why not make it just a little harder to get the youngest and least experienced hands in society squeezing those triggers?

Bear with me, here: what if it were only legal to keep one small firearm, appropriate for personal protection, at most types of private residences? What if people had to keep the rest of their guns off-site, in some kind of biometrically-secured storage facility? These could be similar to storage units, where we seem to have agreed it's safe to keep our important personal belongs.

If someone wanted to do a little skeet shooting or go out during deer season, they’d just have to swing by the storage facility and check out their firearms first, then drop them back off when they were done.

Would this be a deterrent to school shooters? Would it matter if the guns they use weren't already right there at home, just waiting for them - maybe locked up in something that can be broken into; maybe not? Would a disaffected would-be shooter discard the idea if he knew he'd have to drive to the facility and somehow open it with his dad's eyes or his fingerprint, because keys and codes were not used?

Maybe. I mean, I have to think that, in many cases, the answer would be "yes," just as such an arrangement would deter an angry, abusive husband from snapping and shooting his partner. He'd have to take a break from fighting and drive over to his gun-storage unit! That would give him time to cool off - and give her time to get the hell out of there. And it could deter someone hoping to swiftly end their life in an acute moment of despair. During the drive, that despair might dissolve, even just a tiny bit.

I think it could be a promising concept.

Another possibility could be instituting a nationwide minimum age for legal firearm use. Did you know we don't actually have a law at the federal level that provides an age at which a person is deemed old enough, mature enough, even physically strong enough to use a gun? And many states don't have such a law, either.

That means if a kid is eight years old and his parents - or, really, just one parent (and take a guess which one) thinks he's ready, then here you go, lil' sport! Go ahead, see if you can hit the broad side of a barn without blowing a toe off - or worse.

This is unacceptable. We ought to strongly consider making it illegal to operate a firearm - even at home under supervision - before age 16. Or 18! Kids have to be 16 to get their driver's licenses and 15 to drive with their parents in the car. A gun can sure take out a lot more people at once than a car can. And alcohol - less dangerous in the moment by orders of magnitude - has to wait until age 21.

"Unacceptable?" Honestly, no. It's more than that: it's an outrage.

And yeah, I can hear you now: "How would we ever enforce that? How practical is this, really? We can't catch all people giving children access to guns!"

No shit!

We can't catch all speeders or all drunk drivers; we can't catch everyone who drives with an expired plate or who's gabbing on the phone as they weave through the lanes. We can't catch every underage drinker who uses a fake ID or who has one glass of wine at the holidays with their family. We can't even catch all rapists or murderers. Hell, we don't even catch most of them.

But we still try. Not trying is not an option.

Could we stop, say, 10% of people hoping to spontaneously commit gun violence? Could we stop a quarter of them? Think how many lives that could save! Could we inconvenience them just enough to lose the urgency and the momentum that creates fatalities? Even when the only potential fatality is the shooter himself, who wishes to end his life, I believe it's important to try to stop him from succeeding and get him some real help.

Consider, too, that illegality does stop many people. I admit I've always been a rule follower, hesitant to rebel. But even I have visited fancy stores where the only thing keeping me from slipping a breathtaking pair of pumps into my handbag and walking out was the knowledge that doing so is illegal.

When it comes to illegal behavior, plenty of people believe that the risk is greater than the reward, and therefore isn't worth it. Depending on the crime in question, that risk can come in the form of a record attesting to one's criminal history, embarrassment, social or familial shunning, heavy fines, forced, unpleasant community service, and jail time or even prison time. Those last two can, in turn, lead to eviction, job loss, abject poverty, becoming unhoused, the loss of relationships, and the risk of addiction.

Many, many people prefer to avoid those things! So it's not out of the question that a legal restriction on minimum age for gun use could throw a wrench in would-be school shooters' plans, and in many other potential gun killings.

And what about, say, forty years from now? Could we change the culture over time? When most adults get used to new protocol or don't even remember a time before common-sense safety restrictions: that's when a cultural tide turns. Look at seatbelt usage, drunk-driving laws, or the practice of keeping infants’ cribs clear of puffy padding and stuffed animals.

I care just as much about future Americans as I do current Americans. We could plant seeds now for a safer society in the future.

Now, look: It's not like I'm running for office on these ideas. And I'm sure there are untold obstacles to both. I have not done a feasibility study; I have failed to convene even one focus group on the matter.

Rather, what I hope to demonstrate is that, if we as Americans wanted to come together to prioritize the reduction of shooting deaths, from school shootings to suicides to murders and accidents, we could. We could do that. We could float different ideas, try them, learn from what worked and what didn't, and then change our strategy accordingly.

We are not beholden to the Second Amendment as if it were a religious artifact or the witnessed and recorded Word of God. The Second Amendment describes a right, not an imperative. And patriotism must not be wielded as a religion, nor should one shield himself behind it as with a religion. Patriotism is misguided as a form of worship because it was created by humans. We do not worship other humans; that’s messed up. Rather, we worship the Divine.

But even if you do kind of revere America's storied Founders, surely it makes sense that the country they helped create be improved, in their very honor? And wouldn't it be a big improvement if fewer people got murdered or killed themselves with guns here in this country they created - especially fewer children?

Soon, attention will fade from Winder, Georgia. There'll be another such event, and our attention will move on. Then it'll be the presidential election, then it'll be something else, and in three years, we may not even remember what happened at Apalachee High School. But unfortunately, the students, friends, and family of Mason Schermerhorn, Christian Angulo, Richard Aspinwall, and Christina Irimie will never forget.

I'd love to see our currently-reinvigorated Democratic party begin to speak with the GOP, without hysterics on either side, about what could be done to make sure the lowest possible number of Americans lose their lives to gun violence.

Without confiscating the guns.