Inhuman Pain, Blindness, and Grief: My Spring So Far

Or "Why I Haven't Finished Editing Your Book Yet: I'm Sorry"

Starting to sweat now, I barrelled out the door of the Dollar General without so much as a "Thanks; you, too," and made a beeline for the white hatchback. Collapsing behind the wheel, I tore my handbag apart searching for the tiny white tube of salvation: the only thing I'd gone inside to get.

As I did, the horrible drumbeat intensified through my jaw and face. A drop of sweat slid off my forehead and into my eye. Aha! Here it was. I fumbled the tiny cap off, only to see that the end of the tube needed to be snipped with scissors.

I nearly wailed with despair until I realized I'd just flung a set of nail clippers out of my bag. Would those work? Shaking, I jammed the plastic tip into the little clipper and pressed down. I heard a pop. Yes! Smooth, turquoise gel began to flow out.

But there wasn't a moment to spare. I stuck the whole tube into my mouth and squeezed it against my yowling molar. I held the Orajel there for a good thirty seconds as tears of relief fogged my glasses.

Oh, thank you, God. I felt every muscle in my body unkink as I slumped low in the driver's seat, savoring the out-of-body elation of sickening pain evaporating.

This should be getting better by now, I thought once I was back on the road. There was no denying it - I was worried. Panicked, even. Maybe I should go back to the doctor.

I'd had an infection in my jaw before. I have abnormally deep pits in my teeth and take medications that erode tooth enamel, so maybe it was inevitable. This last time this had happened was five years ago, and I'd gotten quick relief with some antibiotics - which stop the pain by quickly controlling the infection - and then I'd had a minor outpatient procedure.

But that pain was still the most torturous sensation I'd ever felt in my life. Under its spell, I had even torn out clumps of my own hair without realizing it. This episode was shaping up to be just as bad, if not worse, and I wasn't about to let it go on a minute longer than it had to.

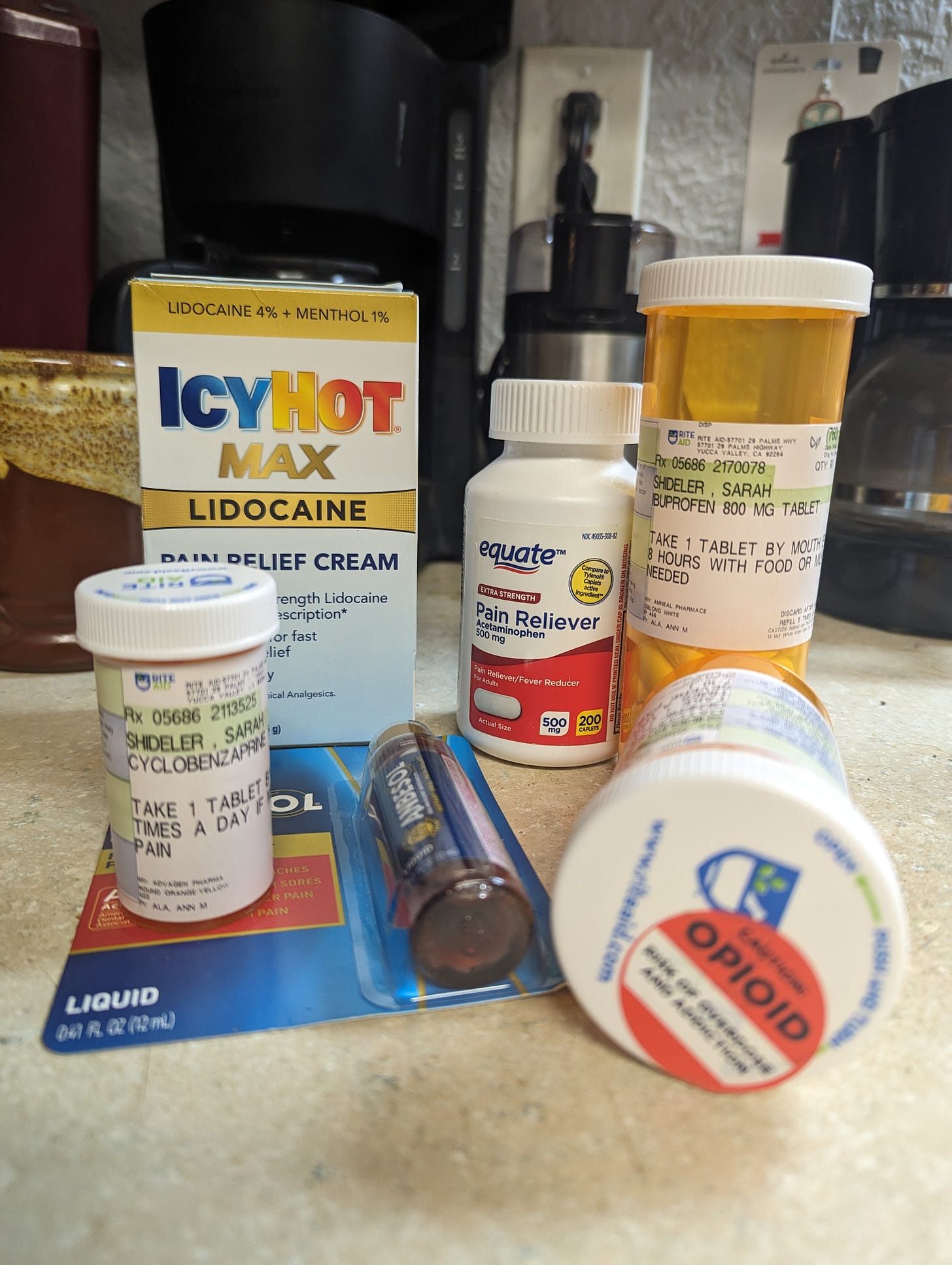

It was clear that the course of antibiotics I had just finished wasn't working. I was going through a bottle of liquid Anbesol and half a tube of Orajel every day - on top of the two prescription pain medications I take for my shoulder injury. If none of that was even blunting the pain, something was very wrong.

So I called my doctor when I got home, and she sent over a course of a different antibiotic. The next day, I checked with my dentist, who agreed. Ironically, I was awaiting an extensive oral surgery to solve this problem once and for all, but the operation could not take place until the infection was under control.

The surgeon had taken a nightmare-fuel X-ray that showed the infection raging from my ear and cheek across my jaw and all the way down my neck. It hurt to talk. It hurt to eat. It hurt to breathe.

By this time, my face and neck were so painfully swollen that I could no longer lie down: the rush of blood flow to my head made the pulsing, reverberating pain unbearable. And I couldn't use an ice pack or Icy-Hot cream to temporarily dull it, either: touching my face in any way was out of the question. Even the sensation of air on my skin from the ceiling fan hurt so much that I lost my balance.

But I could swish ice water in my mouth over my swollen gums to numb them for ten seconds at a time while I waited for the new antibiotic to kick in. So that's what I did, ten seconds at a time - for days. I couldn't work, I couldn't sleep, I couldn't even think - so I simply bore down and waited.

And as I did, I nearly went out of my mind. I came to believe I would surely die at any moment.

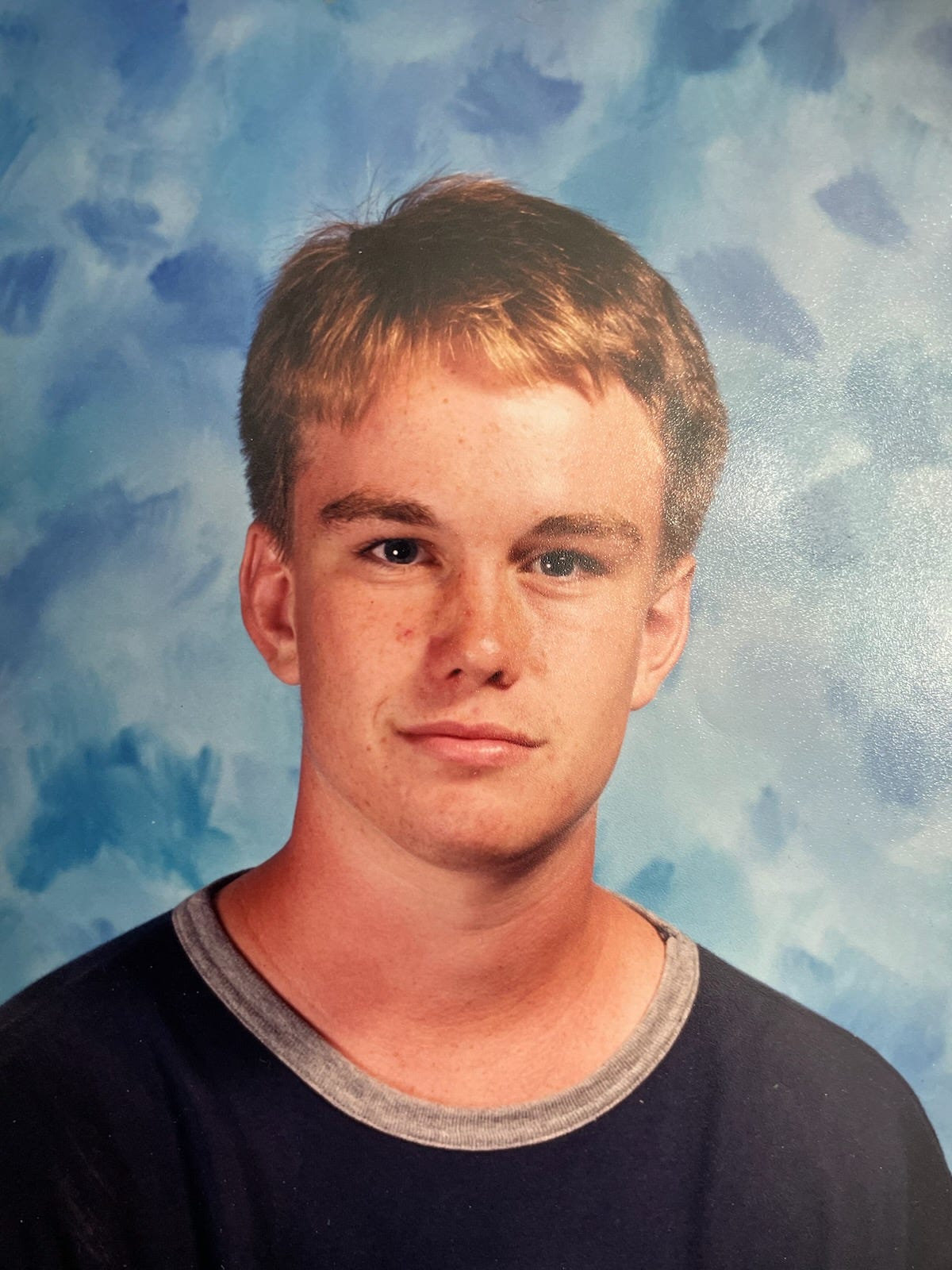

Death had been on my mind lately. About a month before, I had awoken to an awful text from my mother back in Indiana. My stepfather had just gone over to his eldest son's house that morning to visit and check in, as he did every day, and had been devastated to find that he'd passed away. Kyle was only 40 years old.

Kyle and I were not close when he died, but nearly 30 years ago, as tweens, we were thick as thieves. I'd never met another kid who had the same absurdist sense of humor I did. As time went on, though, the laughing stopped. Kyle hurt me in a dreadful way, and we didn't speak for a very long time - more than a decade. Nearly two.

But then, about a year ago, something changed in me. Forgiveness is one of my most deeply-held values, and I began to sense that I could be doing a better job at living up to my ideals. And I wanted to know how Kyle was doing: oddly enough, I had missed him, in a way.

Since he didn't come to our parents' house when my brothers or I were there, I began going out of my way to ask my stepfather how Kyle was doing.

And I think my stepfather - whom I simply call "Dad" - was surprised that I would ask, at first. But I sensed that my concern meant something to him. It meant forgiveness, and I felt sincerely honored to be able to offer it.

Dad shared that Kyle was facing some health challenges, but was excelling in his career as a director at a transportation company. I was glad to hear about his job but sorry for his health struggles. I mean, that's what happens around our age, right? Things crop up.

I didn't expect that he would die.

Kyle had not wanted a funeral, so I did not fly back to Indiana for the informal gathering that was held. Out in California, I began to sift tentatively through recent difficult memories and older happy ones alike in an effort to bring some kind of order to the fact that a 40-year-old man with a great job and insurance and a stable, fortunate family had died so young.

I'm ashamed to say that, after awhile, what freaked me out the most was not my heartbreak for my dad or my other stepbrother or my little niece - although of course I felt those things. Rather, what kept me up at night was the idea that I could die unexpectedly, too. Unexpectedly - and young.

And that ratcheted up my medical anxiety. I'm pretty implacable in most situations, but when weird medical stuff is happening - even to other people - I get freaked out. It's a byproduct of growing up with a father who was often very ill before he passed away 13 years ago.

My body did not know what to do with this odd mix of grief and fear. I started having panic attacks.

The one consolation, though, was that nothing much was wrong with me. Certainly nothing like what Kyle was going through. But then this happened - this infection.

I began to fear that it would somehow get into my bloodstream. What if it happened overnight? Could I become septic? Would I wake up dead? What if my parents lost two kids because I was being stupid?

Unable to reassure me that this was no big deal,

finally convinced me to go to the hospital. He took me three times in two days, actually, though I was only given mild pain relief. I cried. I gagged in pain. I told the staff I couldn't live like this anymore, and was literally met with rolled eyes.Thankfully, sepsis was not a concern. But neither was my anguish. "The pain's not going to kill you," the ER doctor said, visibly - and bafflingly - exasperated with me. "People walk out of here in pain every freaking day." Seeing me immediately drown in my own flood of hopeless tears, she eventually administered shots of Dilaudid, but made sure to tell me that was all she could do. They didn't want to do anything more because I already had an opioid prescription - I'm sure I was labelled “drug-seeking.”

But that opioid prescription didn't mean I couldn't be helped. It just meant that my tolerance was higher. Indeed, each time, the Dilaudid injections I received wore off completely by the time we were home.

Why couldn't the nerve just die? I kept screaming. It should! It had happened last time, and it had saved me. But this was so, so much worse than anything I'd ever experienced. If anything, the nerve seemed to be conducting more pain than ever. It reverberated in constant waves through my ear, across my face, over my chin, and down my neck as regularly as a metronome. I felt every accelerating beat of my heart in my mouth and face.

Under such duress, I couldn't function at all. I could only sit miserably, hour after hour, my whole body braced and contorted against the agony.

Incensed at the lack of care, Dave drove me back to my dentist, where I broke down again. I sobbed that I couldn't take any more of this and the hospital had been no help. The dentist gave me a new prescription for another antibiotic, the third one I'd taken in as many weeks.

"We're really pulling out the big guns here," he said. "If this doesn't work, we'll have to administer it intravenously."

If the hospital would even see me! All I could do was take my new meds and pray. So I did.

That night, I spent the longest and darkest time of my life. By 2 AM, I found myself curled up on the living room floor, utterly depleted, unsure how I'd gotten there. White-hot lightning burned through my gums and the roof of my mouth, pulsated down my chin and neck, and ricocheted in my ear.

"The Good Place" played incongruously in the dark as Dave and Jasmine snored in the next room, but I was as far away from them as I was from my still-grieving family in Indiana. I could only hear my panicked heartbeat. I expected to keel over from a stroke any second.

This is unbearable, I decided, as I lay there on the floor, the awful delirium of truly excruciating pain reaching a fever pitch. This can no longer be borne. I am going to die now.

"Hey," I remember laughing to myself while the mania played with my mind. "This pain is going to kill me, after all!"

Gingerly, I hauled myself up off of the floor. I rummaged through my medicine bag. Maybe there was something I could just ... take all of, and that would do it? The opioids, maybe, or Zoloft? Or I could walk the block and a half out to the middle of the highway and stand there, waiting for a car to come mow me down.

"No," I realized immediately. "That's not fair for the person who hits me." And that one, blessed rational thought was - thank God - the last I knew that night. I think I blacked out.

I must have, because the next morning, I woke up in bed. I'd been asleep somehow! During that awful night, I'd been awake for almost 60 hours, but apparently I'd finally gotten some rest. And I’d even been able to lie down! As I peeled myself off the bed, I realized the strangest thing: my mouth didn't hurt. And neither did my face, or my ear, or my chin, or my neck.

Was I dead?

I wandered out to the living room in a daze. If I was dead, heaven sure looked a lot like our apartment.

Dave looked up from his computer, his brows knitted together in worry. "How's your pain right now?"

"I - uhh. I don't actually have any," I said, utterly bewildered. It had to be those antibiotics! They were working already! It was a goddamn miracle. I couldn't believe it: after all that, after being so sure my only chance at relief was to die, the pain could just ... shut off like that? It seemed too good to be true.

And it was, in a way. The pain has never come back, and my surgery is this Friday. But the meds made me temporarily blind in my right eye.

It started out weeks ago, during the worst of the pain, as light sensitivity. Then I noticed that my vision was a little bit blurred in one eye - and then it was very blurred. At the time, I was in too much pain to care much. But three days after I'd finished my last round of antibiotics, I woke up to normal vision on the left and a strange effect in my right eye that looked exactly like someone had spilled milk all over everything I looked at. Thick, chewy whole milk. Almost totally opaque.

I had always thought of being blind as a blackness encroaching, drawing closer, circling in. But this enormous whiteness? It had a boundlessness, an infinite quality, that absolutely unmoored me.

Suffice to say, I was freaked out all over again.

Again, reading, writing, and editing were out of the question. It made me sick to watch TV. It made me sick to take our dog outside. With no peripheral vision, I was dizzy and queasy every time I moved - I walked into walls and lifted spoons past my mouth.

For the lingering light sensitivity, I had to wear sunglasses inside the house. I even had to order special extra-dark ones - clamped dorkily over my regular glasses, since I don't do contacts - and I strongly considered breaking out the eclipse glasses we'd bought to use for all of 20 minutes.

I just couldn't see to find them.

This was an allergic reaction from one of the antibiotics, I was sure. Yes, it was a very weird one, but one I knew well: about 15 years ago, I'd had a medication side effect that left my right eye crossed for about four months. So as I waited on a doctor appointment, I set about taking the rigorous course of Benadryl I'd utilized last time. Maddeningly, it left me exhausted during the day and wide-awake at night.

But my Gordian knot of emotions about Kyle had still been simmering away on the back burner all this time. It was a mess of sympathy for my dad, regret for Kyle himself and the way he'd died, persistent indignation at the way he'd hurt me so many years ago, and guilt for not being able to fully let that go.

And there was still that through-current of fear that such a death could happen to me. Was it possible that I, who was planning to write books and take trips and do big things, could just unceremoniously die at any time and leave everything I just hadn't gotten to quite yet undone forever?

For heaven's sake, on the morning he died, Kyle had texted Dad a request to bring him an order of stuffed French toast. He'd expected to enjoy a nice breakfast that morning with Dad. Sounds perfect, right? Instead, he'd just ... died.

How the hell was I supposed to live with that kind of uncertainty? How could anyone?!

I was literally blind both to reason and to my immediate surroundings. The simmering in the background of my mind reached a nearly-hysterical boil, and I started having worse and worse panic attacks, even at home. Late each night, sleepless after sluggish days of Benadryl, I'd convince myself that I was not, in fact, suffering a familiar allergic reaction, but was instead developing some awful disease that was stalking me: lurking there, patiently waiting to kill me, too.

And on top of everything, we were planning a beach trip in a week and a half. Should we cancel? Would I throw up in the car from the mismatch between what I could see and how my body was moving? Would I be able to to enjoy the waterfront? Would I even be able to see it in the glare of the sun? I obsessed frenetically about the right thing to do, probably because I felt I had no control over the big stuff.

And for the love of God, I had a bunch of books I was supposed to be editing! But I couldn't stand to look at a screen, even with my good eye: when my good eye registered light, my bad eye felt it and throbbed. I started throwing up not just from lack of peripheral vision, but from stress.

Just as I was about one more day away from another episode of hysterical delirium, the Benadryl regimen suddenly began to work. The spilled milk dried up. I had cried over it plenty, and I can confirm it doesn't help! After weeks, my vision was finally about 80% back to normal. Once again, at the critical moment, I was saved.

Another miracle.

So last weekend, Dave and I took Jasmine for a long weekend in San Diego as planned. We wanted to bring her to the city's famous Dog Beach, a beautiful, off-leash cape where dogs can run around, sniff each other, and go crashing through the waves of the Pacific like the wild wolf-toddlers they are.

Jasmine had a blast, and we did, too (even if I still had to wear my sunglasses and keep pounding Benadryl). On our last night, we walked the hundred yards from our hotel to the waterline to watch the sunset cast its ethereal amber glow onto the sparkling waves.

Dave walked Jasmine through the surf as high tide began to tickle the driest reaches of sand. From a nearby bench, I framed them in one photo after another, love pouring out of my heart, threatening to drench them before the ocean did.

And then I made myself set down my phone and just be present.

The simple fact is that we do not know how much time we have. And we all must do whatever we need to in order to accept that - it's the first and biggest non-negotiable condition of life. Now, with my mind and body freed from having to fight off all-consuming pain, panic, and blindness, I can understand the freedom - indeed, the gift - of not knowing which year or day or hour will be the last.

But I'll be damned if I don't want to use every day the best way I can! Doing so honors God. It honors ourselves. And it honors those whose lives on Earth have come to their conclusion, at least for now. I believe human souls live many lives, but each one is to be fully used up, to the very last drop.

Kyle did that, even if it happened sooner than I expected. So I’ll keep doing it, too. For both of us.

I am sorry to hear about your step-brother. Your commentary on mortality and grief rings very true. Life is way too short.

Thanks for sharing this. Very often it is almost as hard for me to learn about others’ pain as for me to experience my own. So it is rare for me to read something like this. But I’ve always believed that experiencing suffering can help us and others.

I know that experiencing pain can make us humble and bring us closer to God. And I know that having experienced suffering we can minister to those who suffer in the same way we have.

But I am now learning that there is an additional benefit to our pain. I believe it is also a good thing for people who see others suffering, to have the attitude of “There, but for the grace of God, go I.”