The Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant has been sitting on my shelf for too many years. I’ve put it off because I wasn’t sure how well military memoirs written in the 1880s would hold up in the 21st century. But another book has convinced me to read it.

Grant and Twain by Mark Perry details the unlikely friendship of two famous Sams. Ulysses “Sam” Grant and Samuel Clemens met as early as 1866, but their relationship wouldn’t solidify until the end of Grant’s life nearly 20 years later, when the soldier became an author and the author became a publisher.

A business failure bankrupted Grant in 1884. The same year, Grant learned he had cancer of the throat and tongue, likely due to his longtime habit of smoking cigars.

Dr. John Hancock Douglas, who had previously discovered a treatment for scurvy, presented the diagnosis to Grant, telling him that “the disease is serious, epithelial in nature, and sometimes capable of being cured.”

Douglas also knew that the cancer was likely to kill Grant. Grant appears to have suspected the same, as his next stop was to meet with the president of the Century Company to discuss the publication of his memoirs, an endeavor Grant had previously resisted.

When Mark Twain learned Grant was finally writing his memoirs, he launched efforts to convince Grant to let him publish the work instead. Twain offered generous terms. Grant initially felt loyalty to the Century Company, but Twain was persistent and convincing. Realizing what was best for his family, Grant eventually signed with Twain.

All the while, Grant wrote his memoirs as his health deteriorated. He was determined to finish this one last job, as monumental as it was. The goal enhanced his will to live and appears to have lengthened his life by several months.

Grant completed the second volume of his memoirs in 1885, shortly before his death on July 23. It’s plenty impressive that he finished both volumes while battling terminal cancer. But he also maintained a high quality of work throughout the process.

Grant had honed a clear, crisp, utterly unpretentious writing style over the years. In the military and in the White House, he favored precision when issuing orders.

Perry writes:

“[Grant’s] style was understated, almost skeletal. It was this understatement, this obsessive desire for absolute clarity, that had made Grant’s written orders as commander among the most precise of any American military officer; they remain models of clarity in a discipline that often rewards ambiguity. It was this same desire for precision in his orders that would now make him America’s most successful memoirist.”

Twain, who knew a thing or two about writing, held Grant’s prose in high esteem. Perry notes that Twain didn’t even feel the need to edit Grant’s work beyond basic proofreading. It also didn’t occur to Twain that Grant might benefit from some words of encouragement. Grant’s son Fred suggested that a few kind words from Mark Twain would boost the general’s confidence.

Twain was surprised and flattered, and he carried out the suggestion when the opportunity arose.

Perry quotes Twain’s Autobiography, in which he compares Grant’s memoirs to Caesar’s Commentaries:

“I was able to say in all sincerity that the same high merits distinguished both books—clarity of statement, directness, simplicity, unpretentiousness, manifest truthfulness, fairness and justice toward friend and foe alike, soldierly candor and frankness and soldierly avoidance of flowery speech. I placed the same two books side by side upon the same high level and I still think that they belonged there.”

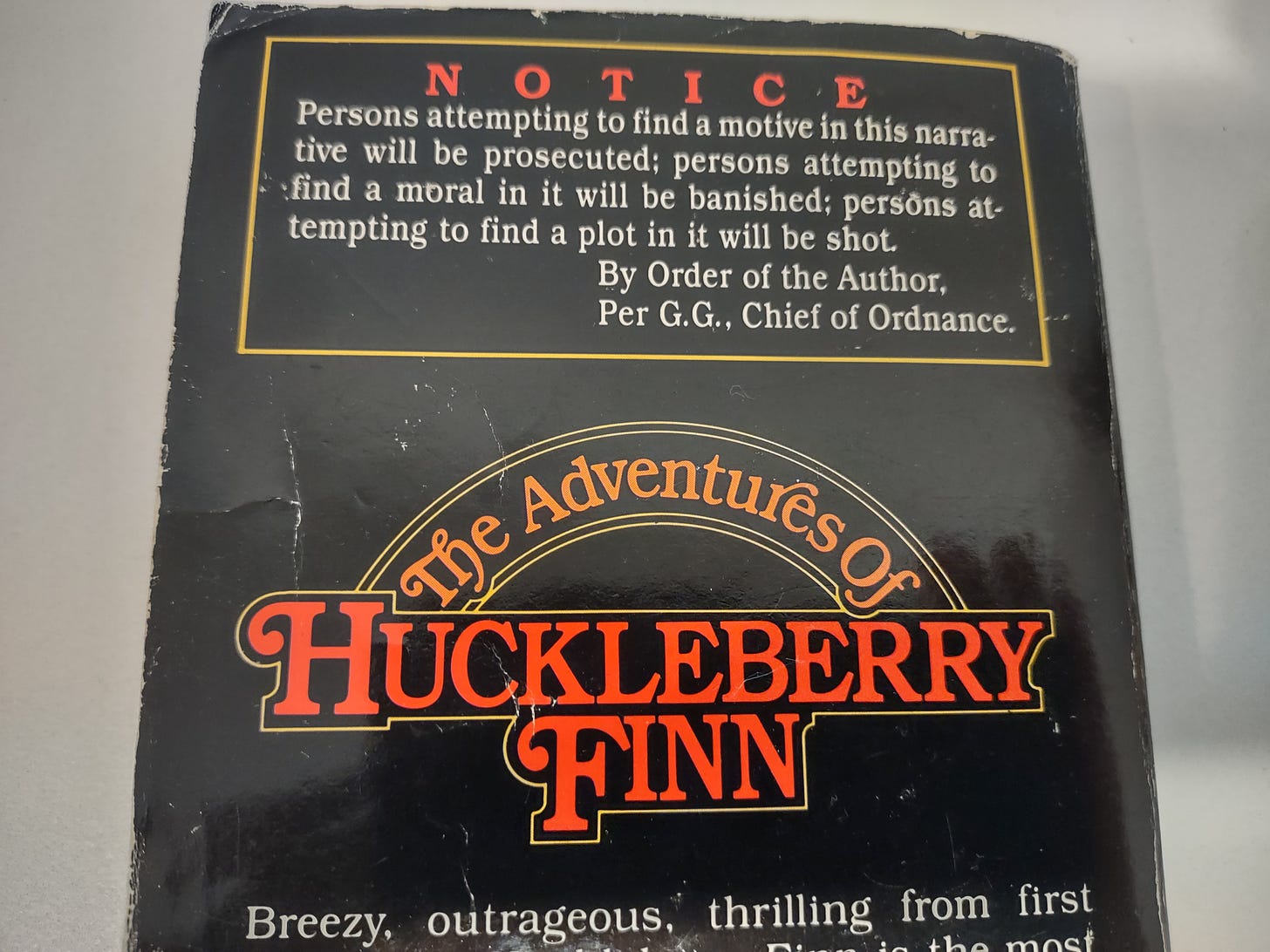

During this time, Twain was finishing The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Linking a classic of American fiction with a classic of American nonfiction, Perry details Twain’s struggles to figure out the novel.

Toward the end of Grant and Twain, Perry suggests that Twain paid tribute to Grant in the famous “NOTICE” at the beginning of Huckleberry Finn (“Persons attempting to find a motive in this narrative …”). The notice ends with this attribution: “Per G.G., Chief of Ordnance.” Twain never confirmed who “G.G.” was, but Perry notes that the author could never bring himself to call Grant by his first name. The war hero and ex-president was, to Twain, always “General Grant.”

Grant and Twain is an engaging, informative book, and it’s relatively brief at 239 pages (in the main part of the paperback edition). Whether you’re interested in history, literature, or both, it’s worth a read.

And now I need to add Grant’s memoirs and a reread of Huckleberry Finn to my queue.

Very underrated president and a true American hero.

The post reconstruction southern apologists intentionally tarnished his name because they hated him so much, and those embellishments made their way into just about every American textbooks. Only now is Grant getting proper credit as the having a successful competent presidency on top of his stellar military career.

His memoirs, while always held in high esteem are also now getting more attention as his reputation has been rehabilitated. I should read them as well. Grant one of the better presidents, and a lot of what he did could be seen as an extension of what Lincoln(the greatest US president) would have done, although likely with less conviction than Lincoln.

Since reading Ron Chernow's seminal work on him, I've been trying to find time to read Grant's memoirs. They were the top selling presidential memoir until late in the 20th century, and absolutely brilliantly written.

Grant was long one of my favorites, but after that book, he is first and foremost the greatest president we've ever had, and one of the top five Americans our country has ever known.