Einstein and Oppenheimer

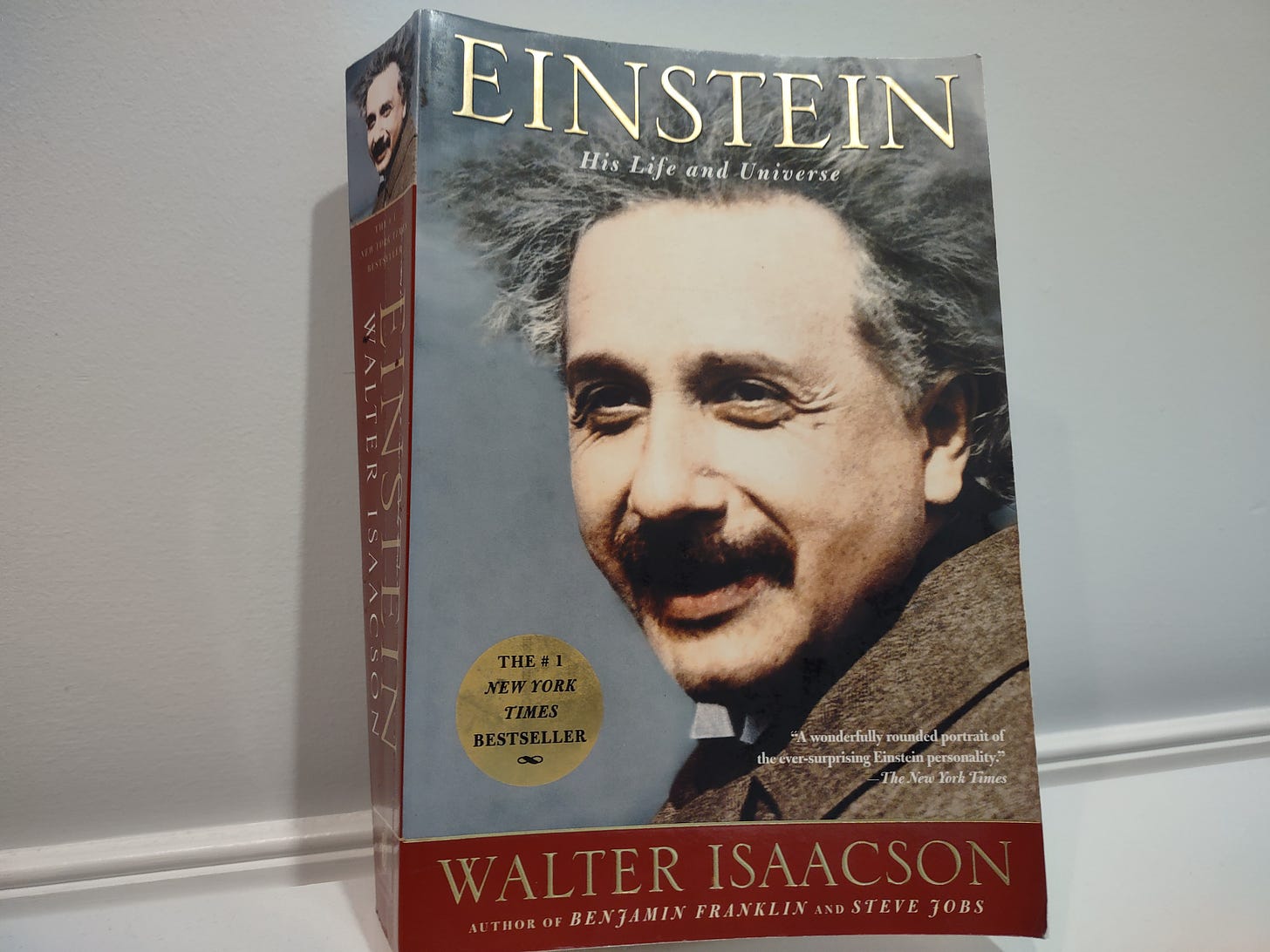

It’s a good time to check out Walter Isaacson’s Einstein biography if you haven’t already.

As much as I love a good comic book movie, I understand that those shouldn’t be the only movies anyone ever sees. Oppenheimer, the upcoming Christopher Nolan film, could be just what I’m looking for.

While some of Nolan’s movies, such as Interstellar, get a little too convoluted for their own good, I’m optimistic that a film based on historical events will ground him and curb those tendencies. Dunkirk, after all, was an excellent historical snapshot of a particular moment in time. Oppenheimer looks like it will dig deeper into the individuals and moral issues. So I’m looking forward to it.

For a good companion book, I recommend Walter Isaacson’s excellent biography of Albert Einstein: Einstein: His Life and Universe. Isaacson, as expected, does a superb job of exploring the man and his work. He translates all the scientific principles so even a layman like me can understand it.

J. Robert Oppenheimer is a minor but notable figure in the grand scheme of Einstein’s life. The atomic bomb itself, of course, looms much larger.

Unlike Oppenheimer, Einstein was not among the physicists recruited to develop the atomic bomb. He wasn’t specifically a nuclear physicist, and he was deemed a potential security risk. When asked for his expertise on the specific problem of separating isotopes that shared chemical traits, Einstein was happy to help the cause, though.

Einstein was a pacifist, so why was he interested in America developing an atomic bomb? Because he worried the Nazis might develop one first.

“Had I known that the Germans would not succeed in producing an atomic bomb,” he said after the war in a Newsweek article, “I never would have lifted a finger to help.”

Once the bombs were dropped, Einstein advocated for a world government.

Isaacson writes:

“He had indeed become circumspect during the war years. He was a refugee in a nation that was using its military might for noble rather than nationalistic goals. But the end of the war changed things. So did the dropping of the atom bombs. The increase in destructive power of offensive weaponry led to a commensurate increase in the need to find a world structure for security. It was time for him to become politically outspoken again.”

This brought him into some disagreement with Oppenheimer, who was skeptical about a global authority’s ability to integrate societies who hold differing values.

Despite his political advocacy, Einstein remained a scientist first and foremost. Isaacson quotes him as saying, “Politics is for the present, while our equations are for eternity.”

Einstein and Oppenheimer came into more frequent contact when the latter took over as director of the Institute for Advanced Study. Einstein was officially retired but continued to work there.

Isaacson describes Oppenheimer as follows:

“A brilliant, chain-smoking theoretical physicist, he proved charismatic and competent enough to be an inspiring leader for the scientists who built the atomic bomb. With his charm and biting wit, he tended to produce either acolytes or enemies, but Einstein fell into neither category. He and Oppenheimer viewed each other with a mixture of amusement and respect, which allowed them to develop a cordial though not close relationship.”

Years later, Oppenheimer said of Einstein, “There was always in him a powerful purity at once childlike and profoundly stubborn.”

During the era of McCarthyism, Oppenheimer got on the wrong side of Lewis Strauss of the Atomic Energy Commission. Oppenheimer’s wife, Kitty, and brother, Frank, were Communist Party members before World War II, and Oppenheimer himself “had associated freely with party members and with scientists whose loyalty came under question,” according to Isaacson.

So, in 1953, despite the fact that his security clearance would have expired soon anyway, Oppenheimer’s enemies drew him into a hearing to determine whether he should retain that aging security clearance.

Einstein thought the bureaucrats were being ridiculous. But he also thought Oppenheimer just should have told them off and gone home.

Isaacson writes:

“Einstein considered Oppenheimer ‘a fool’ for even answering the charges. Having served his country admirably, he had no obligations to subject himself to a ‘witch hunt.’”

Oppenheimer, however, decided to fight the matter out.

Isaacson quotes Einstein as saying, “The trouble with Oppenheimer is that he loves a woman who doesn’t love him—the United States government.”

When the Institute’s faculty created a petition expressing support for Oppenheimer, Einstein immediately got on board and urged others to do the same.

Writing to an Institute trustee, Einstein described Oppenheimer as “by far the most capable Director the Institute has ever had” and said that dismissing him “would arouse the justified indignation of all men of learning.”

The AEC deemed Oppenheimer a loyal American but also a security risk, so they revoked his clearance. The Institute, however, kept him on as director.

Of course, this is a biography on Einstein, not Oppenheimer, so there’s far more than what I’ve described above. And it’s very much worth reading.