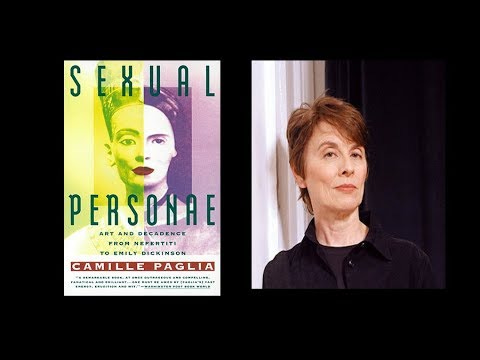

Camille Paglia on the Capitalist and the Artist

Beginning an exploration of one of the greatest cultural critics and literary analysts of all time

Early in her first book and bestseller, Sexual Personae, Camille Paglia, says, “The capitalist and artist are parallel types: the artist is just as impersonal and acquisitive as the capitalist, and just as hostile to competitors.”

I understood this observation all too well. I had played in a variety of bands since high school and into my forties. The local world of rock and roll was even more amoral than some car-dealership guy and his buddies having affairs or going to strip clubs. As members of the rock and roll tribe, many of us put off marriage and families for years, making us highly irresponsible on a daily basis, while local businessmen had families, kids, attended the local church and, of course, had their neighbors to consider when planning their shenanigans.

Paglia’s view of capitalist and artist is the great tension between the Apollonian and the Chthonian, which means of the earth. She wrote:

“Both the Apollonian and Judeo-Christianity traditions are transcendental. That is, they seek to surmount or transcend nature.”

The capitalist is involved in creating the abundance of goods and services, hopefully profiting from every exchange, and improving the human condition, which increases the abundance of life’s stuff. However, she adds:

“It is the Chthonian realities which Apollo evades, the blind grinding of subterranean force, the long slow suck, the murk and ooze. It is the dehumanizing brutality of biology and geology …. the squalor and rot we must block from consciousness and retain our Apollonian integrity as persons.”

She would also add that the artistic endeavor involves seeking out ecstasy through sex, drugs, and rock and roll. The long nights in a bar of dancing, sexual attraction, and simply being overtaken by the music is a modern sprint of Dionysian experience, or the Chthonian.

On the surface is society, roads, the known, ergo, the Apollonian. The Chthonian is the horror of biology—sex, plagues, and death. It’s geology and weather and the wiping out of populations from earthquakes, floods, and volcanoes, to name a few culprits.

“Nature cares for species, never individuals: the humiliating dimensions of this biologic fact are most directly experienced by women, who probably have a greater realism and wisdom than men because of it.”

I went from music to aviation, or from the Chthonian to the Apollonian in the late eighties. At a charter company I piloted a Piper Aztec, a twin-engine aircraft with well over ten thousand flight hours on the airframe. The Aztec (a great name that might lose out to the current woke mob) was used for thunderstorm research in the 1960s due to its strong fuselage framed by its tubular steel skeleton.

I left the smoke (yes, there was still lots of smoking in bars), the women, and music for a life of piloting several nights a week by my lonesome above the Lake Erie shoreline, often landing at Buffalo digging out of the ice age. Between Pittsburgh, Cleveland, and Buffalo, I drove the Aztec from eight in the evening until eight in the morning in the dead of winter.

I craved and had the company of adults, increased my pilot skills, made money, and continued to progress in the wide-open field of American aviation. My love of flight had propelled me since childhood. My new professional life was like a guy’s first week in Spartan bootcamp, with a smile still on his face.

I flew at lower altitudes (five or six thousand feet) at top speed (180 knots) to hand-off the checks to the courier, who then drove the cancelled checks to the bank for processing. I kept a close eye on the instrument gauges and listened for telltale signs of engine problems. One night upon landing, the landing gear collapsed. I skidded along the pavement and shut off the fuel valves, killing both engines, eyeing the cabin door for a fast exit.

I now know I was flying through the Chthonian soul of Nature herself, armed with a ship and a map. The night’s beauty never pushed Nature out of the way. The cold, the four-thousand-year-old Lake Erie, and the vast night sky were treacherous and unforgiving.

A few of our pilots, who had the flight hours and experience, took the controls of the Piper Aerostar, a plane whose name matched its good looks and speed (unlike my relatively slow and fat-looking twin). Midwinter, flying this hotrod, one of our pilots experienced a sudden engine failure, lost control of the plane, and plummeted into the dark waters below.

That pilot knew, like the rest of us, that he was making his way among the uncertainties of modern flight, yet he found strength in the beauty of an invention barely one hundred years old, the product of the Wright Brothers’ brilliant intellects. He had pride in his own skills, understood the science of flight, enjoyed the cockpit with its Star Trek shuttle-craft look. I know he enjoyed the creature comforts that we all did, especially if one lost the heater on occasion and froze until landing. And I’m sure this fellow deeply appreciated his cup of coffee, often still warm since each leg we flew was well under an hour.

Here’s Camille on the need for the Apollonian, which is the need for human flourishing:

“Nature breaks its own rules whenever it wants. Science cannot avert a single thunderbolt. Western science is a product of the Apollonian mind: its hope is that by naming and classification, by the cold light of intellect, archaic night can be pushed back and defeated.”

Editor’s Note: Also check out the following podcast by

at 's Substack expounding on Paglia's greatness: