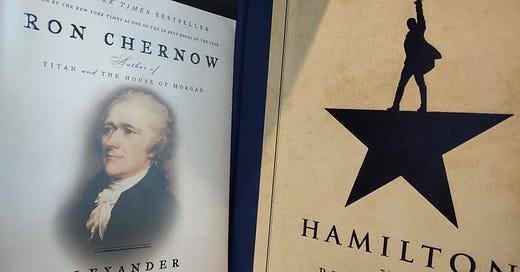

The Broadway musical Hamilton captured much of the historical spirit of the biography Alexander Hamilton by Ron Chernow. But the musical didn’t just cut the first name from the title; out of dramatic necessity, it also cut a whole bunch of corners when adapting this several-hundred-page book for the stage.

The musical gives the impression that Alexander Hamilton stayed on as secretary of the treasury throughout George Washington’s two presidential terms and into John Adams’s term, until “Adams fires Hamilton,” as the lyrics go.

But that isn’t how it went down.

Hamilton left office early in 1795, but he kept in touch with Washington and did indeed help with his farewell address. He also remained friends with Adams’s cabinet members and corresponded with them, always willing and eager to offer his advice. Chernow phrases it brilliantly when he describes Hamilton as “promiscuously dispensing his opinions.”

Shortly after Adams took office, Hamilton offered him advice as well, much as he had done with President Washington. President Adams, however, didn’t take too kindly to it.

Chernow quotes Adams’s reaction to the “long, elaborate letter” filled with unsolicited policy suggestions. Adams said it included “a whole system of instruction for the conduct of the President, the Senate and the House of Representatives. I read it very deliberately and really thought the man was in a delirium… I despised and detested the letter too much to make a copy of it.”

This was merely the beginning of a feud that would outlast the turbulent 1790s and infect the 1800 presidential election. The two men, both brilliant in many other respects, brought out the worst in each other.

“Both were hasty, erratic, impulsive men and capable of atrocious judgment. And both had blazing gifts for invective, which they eventually turned against each other,” Chernow writes.

While the United States prepared for the possibility of war with France, Washington returned to public life one last time to serve as a figurehead of the reformed army. To Adams’s annoyance, Washington insisted that Hamilton serve as inspector general—an appointment that introduced new opportunities for Adams and Hamilton to get on each other’s nerves.

And sometimes the irritation was entirely justified. Francisco de Miranda, a native Venezuelan, had long fantasized about Britain and America joining forces to push Spain out of Latin America, and he seduced Hamilton with this fantasy in 1798 (though nothing ever came of it, thankfully).

The episode demonstrated “a further deterioration in Hamilton’s judgment once he no longer worked under Washington’s wise auspices and was left purely to his own devices,” Chernow writes.

Adams, upon learning of the scheme, was aghast. But then he exceeded the completely justified concerns and dove into his own paranoid fantasies, imagining that Hamilton was also plotting to turn the United States into a British province, with Hamilton himself at the helm.

Thomas Jefferson, leader of the opposition party, had his own feud with Hamilton going back to their days in Washington’s cabinet. Interestingly, though, at times both Adams and Hamilton seemed to prefer having Jefferson in power than each other.

“Rather than make peace with John Adams, [Hamilton] was ready, if necessary, to blow up the Federalist party and let Jefferson become president,” Chernow said, after describing Hamilton as “congenitally incapable of compromise.”

Adams, for his part, said:

“Hamilton is an intriguant—the greatest intriguant in the world—a man devoid of every moral principle—a bastard and as much a foreigner as Gallatin. Mr Jefferson is an infinitely better man, a wiser one, I am sure, and, if President, will act wisely. I know it and would rather be vice president under him or even minister resident at the Hague than indebted to such a being as Hamilton for the Presidency.”

As the musical mentions, Hamilton indeed “publishes his response” to Adams’s entire presidency (though this was after the Reynolds Pamphlet in which he confessed to an adulterous affair, not before, despite the order of the Hamilton soundtrack).

“Hamilton found it hard to refrain from vendettas. He would be devoured by his dislike of someone, brood about it, then yield to the catharsis of discharging his venom in print,” Chernow writes.

Hamilton originally intended his Adams indictment for consumption among Federalist leaders only, though Republican newspapers got hold of it and started publishing excerpts that suited their partisan purposes. So, Hamilton thought it best just to get the whole thing out in the open on his own terms.

It did not go well for him or the Federalists.

Chernow writes, “In ‘The Reynolds Pamphlet,’ Hamilton had exposed only his own folly. In the Adams pamphlet, he displayed both his own errant judgment and Adams’s instability.” [italics in the original]

Chernow sums up the quarrel nicely: “Like most people, Hamilton and Adams were preternaturally sensitive to flaws in the other that they themselves possessed.”

There is, of course, much more to the feud, as well as the tensions with France, Hamilton’s military role, and the contentious 1800 presidential election.

The musical understandably glosses over most of this in the interest of narrative momentum. Act II spends much more time on personal matters such as the Reynolds Pamphlet and the tragic death of the Hamiltons’ eldest son, Philip, then jumps to the election, conveniently skipping over Hamilton at his most unhinged.

I was fortunate enough to see the musical on Broadway before the pandemic, and it’s a great work of theatre. As a historical account, it’s just the Cliffs Notes. Read Chernow’s book for the full, sprawling picture.